Ainu you when?

It might surprise you to learn that the term Ainu – defined as “indigenous people of Japan” – is likely more familiar to Americans who solve crossword puzzles than it is to many Japanese. Archaeological and genetic evidence shows clearly that the Ainu were the first people to settle on the northern island of Hokkaido and quite likely settled parts of northern Honshu as well. However, there is some question regarding the timing of their arrival and the timing of the arrival of humans from the south. Let’s take a look at both.

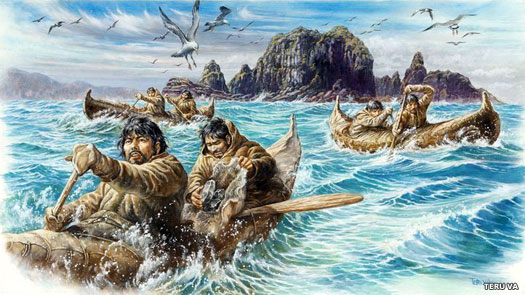

Like its British counterpart, there were almost certainly periods when Japan’s islands were connected to the Asian continent by either ice or land bridges and it’s almost equally certain that the first humans reached the islands by these routes. These early humans, arriving perhaps as long as 40,000 years before present (BP), would have most likely been hunters pursuing large animals such as mammoths across a land bridge from Siberia onto what is now Hokkaido. Another theory holds that there was also a large migration from southeast Asia either by land or water. The recreation below (by Tera Vu from historyfiles.co.uk) depicts boatmen of the Upper Paleolithic period moving westward from Kozu-Shima an island about 60 kilometers east of Honshu.

There is little debate, however that humans used ice and land bridges during the last great glaciation (about 30,000 years BP) to cross from mainland Asia to present day Japan. They likely came from the northeast and used either land or ice bridges. Humans might also have arrive by boat when sea levels were some 150 meters lower than the present time from the southeast areas of the continent by 20,000 years BP and possibly as early as 35,000 years BP. Those coming from the northeast settled mainly on Hokkaido and became the Ainu. Those from the southeast first settled on Okinawa and are known as Ryukyu – the ancestors of modern Okinawans. Most Japanese view the Ainu and Ryukyu as ethnically distinct from them.

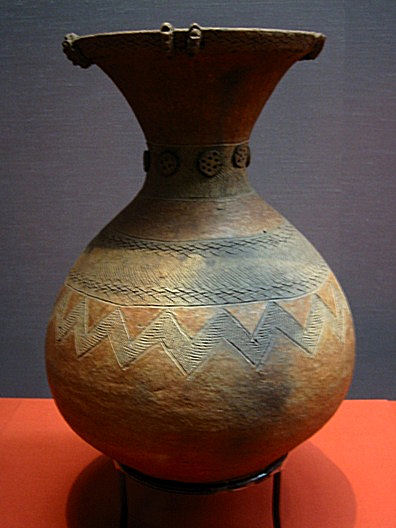

The era of Japanese pre-history from about 12,000 BCE to 300 BCE is known as the Jōmon period. Its name is drawn from the first pottery that appeared on the islands. Genetic testing indicates that these people likely migrated from the area around Lake Baikal crossing a land bridge to Hokkaido before sea level rise from melting glaciers isolated the island about 12,000 years BP. These people are the genetic ancestors of Hokkaido’s Ainu

The name Jōmon means cord-marked or patterned and it stems from the pottery style these people used as seen in this example from about 7,000 years ago.

(From The History Files)

Once the islands were severed from the mainland, limited resources forced the Jōmon to abandon any livestock they might have brought with them and hunt to near extinction any fauna that had reached the islands independently. The people adapted by switching their diet to foraging and fishing to survive. This lifestyle supported the Ainu for thousands of years.

Between 7,000 and 3,000 years BP, the climate of Earth’s northern latitudes became drier in a period known as the Holocene Climactic Optimum. This allowed late Neolithic cultures around the world to become somewhat more sedentary and settle into villages and the Ainu were no different. The largest of their villages covered about 40 hectares (100 acres) and supported nearly 500 people.

The Ainu called Hokkaido “Ainu Moshiri” (“Land of the Ainu”) with some groups living mainly along Hokkaido’s warmer southern coast with fishing as their primary means of support while others lived inland engaging primarily in foraging. Evidence also points to periodic shifts in location that seem to have had climate as the determining factor. There is evidence that over time, they engaged in trade with the somewhat different Jōmon culture as it adapted farther south.

While humans in the western parts of Asia and in Europe began developing agricultural communities around 6,700 BCE, there is little evidence that the Jōmon culture in Japan was doing so. Although their pottery gained in sophistication and fineness they remained largely fishers and foragers until the arrival of a new Sino-Korean group that began as a trickle about 3,000 years ago and continued in ever increasing numbers until about 300 BCE when the new group – the Yayoi (also named for it style of pottery)

(Wikimedia Commons – Public domain)

became the dominant presence first on the island of Kyushu then on Honshu.

Yayoi – Yah boy!

The Yayoi period (300 BCE – 300 CE) brought two critical innovations and one important change to Japan. The innovations were rice farming and a class structured society and the change was linguistic. Their language replaced those spoken throughout the islands and all modern Japanese dialects appear to have descended from the proto-Japanese the Yayoi brought with them from the mainland.

Some historians speculate that the Yayoi “invasion” was sparked by large numbers of Korean (Old Choson) refugees fleeing their peninsula as it was being conquered by the Chinese Yan kingdom. There’s no hard evidence to support this but rice farmers from the mainland had been trickling into Japan for nearly six centuries without exerting any measurable influence and the timing of this influx precisely parallels the timing of the Chinese conquest.

A fascinating figure arose in the latter part of the Yayoi period. This would be Queen Himiko. By the year 100, with a class system firmly in place, about 100 clans ruled most of the Japanese archipelago. Sometime around the year 220, Queen Himiko came to rule the Yamato clan – the largest and most powerful clan in Japan at the time.

Her reign is recorded in several contemporary and near contemporary histories including the Wei Zhi. According to the website The History Files,

Himiko is described as a shaman, practicing magic in her spare time, while having come to power through many years of war and conquest. Those wars have decimated the number of chiefdoms, according to Chinese records, cutting them from over a hundred to around thirty. In her later years Himiko is effectively supreme ruler of Japan (Wō or Wa to the Chinese).

However, there’s little mention of her in the local mythology surrounding Japan’s establishment.

Tennō anyone?

Tennō is the Japanese word for “heavenly sovereign” or, more easily, emperor. According to legend, the first emperor of Japan was Jimmu and he ruled Japan from 660 BCE to 585 BCE. He is reputed to have been a direct descendant of the sun goddess Amaterasu.

(Wikimedia Commons woodblock by Tsukioka Yoshitishi – Public domain)

Two other legendary dynasties followed Jimmu’s rule – the Ōjin and the Keitai. Two books of Japanese lore, the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki combined these three legendary dynasties into one long continuous genealogy. This is a critical step, particularly as regards the Meiji Restoration in 1868 that ended the period of the Shogunates and restored imperial rule. The ruling family draws its legitimacy from this heavenly descent of which veneration of Jimmu is a critical element.

For the Ainu it didn’t turn out so well

Before we leave Japan for St. Louis, our next stop on Todd’s Olympic tour, I need to take a small look back at the Ainu because although they were more or less left alone for much of the history I’ve so briefly summarized here, their situation turned quite dark following the Meiji Restoration.

After the Meiji Restoration, people from mainland Japan started emigrating to Hokkaido as Japan colonized its northernmost island. Perhaps taking its inspiration from the treatment of indigenous people in the American West, the government codified a number of discriminatory practices in the 1899 Hokkaido Former Aborigines Protection Act which displaced the Ainu from their traditional lands to the mountainous barren area in the island’s center. Not only did they lose their traditional lands to these edicts but their language and cultural practices were also outlawed.

After more than a century of legal discrimination during which their language and culture was driven to the edge of extinction, the Ainu gained parliamentary recognition as a people with a “distinct language, religion, and culture” in 2008. This small gesture, however, contained no statement of rights, no restitution, and no apology for more than a century of discrimination. Today, much of the Ainu population remains poor and politically disenfranchised.

Thank you for a really interesting historical recounting of Japan. The Ainu, like most every aboriginal people in history have had to battle an insidious form of genocide. Indiscriminate slaughter followed by extreme discrimination and relocation. Sad business…

You’re welcome and I agree. It’s among the reasons I try to present these stories with a sympathetic point of view while at the same time noting that the natives themselves don’t need to be portrayed as some mythically noble people. Often, they weren’t.

However, I think we ultimately all become better people if we can acknowledge not only our own sins but the sins of our fathers as well. Although my family didn’t arrive in the U.S. until the late 19th and early 20th centuries, I benefitted from their arrival in a country built largely on slave labor and on appropriating (e.g. stealing) land and resources from indigenous people.