The last week of this trip begins with another long bus ride for me and, inevitably, another history lesson for you. The last nine photos and one video in the photo album about Geirangerfjord linked in yesterday’s post are from the first stop we made in the morning after leaving the hotel. For those of you who are not inclined to look back, I’ll repost that link here. The vantage point for these pictures is among the most photographed in Norway. If you search the web for images of Geirangerfjord, you are likely to see scores of photos taken from this point – nearly all of which are better than the ones I took.

As we clamber back onto the bus from this brief photo stop, let’s think for a moment. Poor Norway. Although this is my seventh day here, it seems that most of the history I’ve written has focused on its Scandinavian partners. So, today, I’ll focus a bit on this land. But first, a last look back at Geiranger.

Toward the top center of this picture. you can see a bit of the “Eagle Road” or Ørnevegen in Norwegian. This road that runs from Geiranger to Eidsdal gyrates through 11 hairpin turns (or switchbacks) on a climb that reaches a point 620 meters above the fjord. In a search to confirm the height noted in my scribbled notes, I came across this video of a bicycle ride down the road. While some of the views are astonishing, people prone to kinetosis (motion sickness) should watch warily.

As you take a few moments to recover, I have great confidence that you can recall some of the “fun facts” I’ve previously disclosed such as the percentage of the country that’s glaciated (3%) and the amount of arable land (2%). Or that Norway generates nearly all its energy from hydroelectric power while being one of the world’s foremost exporters of natural gas and oil. But now it’s time to add some depth to our view of Norway.

Before I do, though, I’m going to detour a bit off topic and editorialize. I promise to be brief. I want to comment on the devolution of debate and lack of subtlety of thought that pervades current American politics. Rather than giving you substantial exposition, here is my terse summation: Significant (and even sometimes apparently straightforward) questions rarely have simple answers and simple solutions to important problems are equally rare.

Here’s an illustration that brings in an element of Norwegian history: The Constitution of the United States is generally acknowledged as the oldest such document in the world. What country has the second oldest constitution? Ask the Norwegians and they will likely tell you Norway. Ask a Pole and he (or she) Will Likely provide a different answer.

The U S Constitution was drafted in 1787, ratified in 1788, came into force in 1789 and, with its 27 amendments, remains in force today in 2015. Poland adopted its first constitution on 3 May 1791 making it the oldest in Europe and second oldest in the world. However, that constitution remained in force fewer than two years. Poland had three constitutions in the 19th century, three in the second Polish Republic that lasted from 1919 to 1939, yet another when the country was the People’s Republic of Poland (1945-1989), and a Small Constitution that governed the country until 17 October 1997 when it’s current constitution came into effect.

The Constitution of Norway was signed and dated on 17 May 1814 and, with amendments, remains in effect today. So, is it reasonable for Norwegians to claim the oldest constitution in Europe and second oldest in the world? Or, does that claim still reside with the Poles despite the fact that they’ve had nine different constitutions since passing their first one in 1791? A simple question that requires a subtle answer.

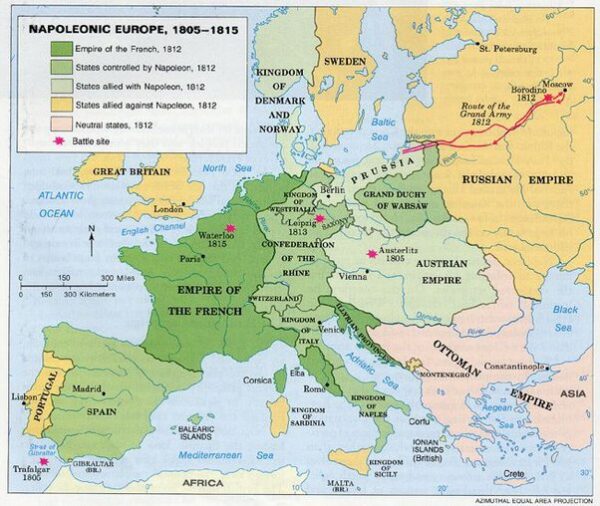

So how does this all affect Norway? First, we need to take a brief look at the Napoleonic Wars of 1803-1815. The Kingdom of Denmark-Norway had remained neutral for the first third of the 12-year span but joined in the battle in 1807 as something of an ally to Napoleon after Britain had destroyed much of its naval fleet particularly in the second Battle of Copenhagen.

(Map from Quora.)

By December 1812, a defeated Napoleon’s last troops left Russia to return to France. Sensing an opportunity, Sweden joined with Prussia, Austria, and several smaller nation states to form the War of the Sixth Coalition against the French Emperor. These hostilities reached their apex at the Battle of Leipzig or, as it is sometimes called, the Battle of Nations because it involved over 650,000 troops and was the largest single battle fought in Europe prior to World War I.

Napoleon’s defeat at Leipzig essentially isolated Denmark-Norway and the kingdom fell to the coalition. In the Treaty of Kiel, signed in January 1814, Norway was ceded to Sweden. This action spurred the Crown Prince of Denmark-Norway, Christian Frederik to establish a Norwegian Independence Movement.

(Christian Frederik – Portrait from The Royal House of Norway – Kjartan Hauglid, The Royal Court).

(It’s likely that his real aim was reunification with Denmark rather than true Norwegian independence but that requires another long and subtle discussion that you can research on your own if the inclination strikes.)

But now, the situation grows even more complex and crazy. Clearly drawing inspiration from the U S Declaration of Independence, and the U S and French constitutions, the Constitution of Norway was simultaneously traditional and quite radical. First, it retained a monarchy in part because the members of the Constituent Assembly wanted to avoid directly emulating the Americans and the French and in part because they thought it would facilitate a reunion with Denmark. It also retained an official constitutional church again establishing a contrast with the U S Constitution and the French Declaration of Rights.

At the same time, while they maintained the monarchy, they radically limited the king’s powers. You might recall from an earlier post that I remarked that much of the social structure we see in Norway and Scandinavia today stems from the fact that their monarch is chosen by the will of the people rather than by divine right and inheritance. This happened at Eidsvoll when the assembled chose Christian Frederik as Norway’s King making him, in fact, an elected king.

The 1814 document included language protecting freedom of speech, guarding against unreasonable searches and seizures, essentially put control of the official church under the elected body, and enfranchised about half of all Norwegian men. Like the American Constitution, Norway’s Constitution has been amended from time to time including amendments to permit the formation of a union with Sweden, granting all men the right to vote in 1898 and universal suffrage in 1913 seven years before women and 11 years before Native Americans were granted the right to vote in the United States.

We’ve reached the town of Lom. Let’s hop off the bus and take a look around.

The river Bøvra runs through the center of Lom and, like so many of the rivers and streams one might see traveling through this part of Norway, the water is simply pristine.

The village lies in the midst of the highest mountains in northern Europe at the edge of the Jotunheim Mountains and the national park of the same name. It is home to the Norsk Fjellmuseum (Norwegian Mountain Museum) and that building has a sod roof that is commonly seen throughout southern Norway.

Lom is also home to a stave church believed to have been built in 1158. Throughout the tour, our guides have made a point of highlighting the stave churches (and I believe I had a link to the Wikipedia page in a previous entry). Apparently, only two medieval stave churches remain outside of Norway. For those of you who didn’t notice or follow that link, Wikipedia describes a stave church as “a medieval wooden Christian church building once common in north-western Europe. The name derives from the buildings’ structure of post and lintel construction, a type of timber framing where the load-bearing posts are called stafr in Old Norse and stav in modern Norwegian.”

Unfortunately for my readers, as a nominally Jewish and behaviorally atheist heathen man, I have to admit that these structures bore little interest for me. Fortunately, I did take a photo of the church in Lom and you can see it with other pictures of the town and its surrounds in this album.

I have one other noteworthy fact for you about Lom. It is the birthplace of Knut Hamsun (born Knut Pedersen). He didn’t grow up there because his family moved much farther north to Hamarøy when he was age three. However, Hamsun was a Norwegian novelist who was the second of the three Norwegians to win the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Because Norwegian law requires bus drivers to have a periodic break for a minimum of 45 minutes, we had time for a cuppa and a nice walk about this picturesque village before once again filling the bus for the drive to Lillehammer where we would stop for lunch.

Hi Todd,

I really enjoyed this,as I did having your company on the trip. You are certainly a talented writer who keeps the reader’s attention. I trust that you have been well.Looking forward to future blogs.

Frank, as always, a pleasure to hear from you.