Those of you who are, say, over 30 years old, possibly have some memory of the 1994 Winter Olympics that Lillehammer hosted. However, it’s probably not a stretch to say that my most vivid memory of that Olympics is quite different from the one the broader public likely retains. Two tiny facts before I prompt those memories. First, Lillehammer is the northernmost city to host the Winter Olympics and it was the first to host a Games only two years following the previous Winter Games.

I’d guess that for most of you your memory of the Lillehammer Games centers on this pair of names – Nancy Kerrigan and Tonya Harding. And for those few among you who still don’t remember, perhaps this video from 6 January 1994 will help:

However, my strongest memory isn’t of the kerfuffle between the two rival American skaters. Rather, I have a clear memory of the closing ceremony.

The Bosnian War, which had its seeds in 1991 when the Yugoslav republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina declared its independence from Yugoslavia, was raging in 1994. One of the effects of this war was visiting significant destruction on Sarajevo, the host city of the 1984 Winter Games. The resulting theme – “Remember Sarajevo” – permeated the Lillehammer games from their outset. Beginning at the opening ceremony, the theme built until it culminated in many moving moments in the closing ceremony finally reaching its climax when all the spectators raised flashlights with the inscription “Remember Sarajevo.”

As a town, Lillehammer (more photos here) also played a role in World War II. Norway has something of a mixed history with regard to World War II and the Nazis. The Germans invaded in April 1940 and occupied the country in a matter of days.

Prior to the invasion, although the government had maintained an official policy of pacifism and neutrality, there were elements in the government that didn’t want to be at war with Britain. There were still other elements, notably Vidkun Quisling, the leader of a fascist party in Norway. Quisling personally met with Adolph Hitler in December 1939 to actively encourage a German invasion of Norway. Like Hitler, Quisling was a virulent anti-Semite and, on the first day of Germany’s invasion, he commandeered the Norwegian national radio and declared himself prime minister. This didn’t please the Germans as they preferred to create at least an illusion of legitimacy after they invaded and occupied a country. True, this usually came about by coercing elements in the governments of a defeated country to acquiesce to their demands but that was their pattern and Quisling had disturbed it.

However, when the Storting (Norwegian Parliament) refused to surrender, the Germans recognized Quisling and demanded that King Haakon VII formally appoint him prime minister. The king stated he would abdicate before acceding to that demand and eventually, the Germans simply installed Quisling as the titular prime minister. The real power was held by Reichskommisar Josef Terboven and the former’s name has since become synonymous with traitor. Vidkun Quisling holds the same place for many Norwegians as Benedict Arnold does for most Americans.

While Quisling led the official cooperation with the Nazis and about 15,000 men reportedly volunteered to fight with the Nazis, there was also clearly a resistance movement among the populace – with the aforementioned sabotage of the heavy water plant at Vermork possibly being the most important single act of resistance. (Many Norwegians also wore paper clips to subversively symbolize sympathy with the Jews who wore the yellow Star of David. Johan Vaaler, a Norwegian invented the paper clip and, because Norway had no patent office, filed for a U.S. patent in 1901. The children of Whitwell Middle School in Whitwell, Tennessee added another layer of symbolism when they began a project that led to establishing the Children’s Holocaust Memorial. This was beautifully documented in the 2004 film Paper Clips.) There were, perhaps, three times as many volunteers for the resistance as there were collaborators with the Nazis. Nevertheless, in spite of Quisling’s welcome acceptance of the occupying forces, because the Germans appropriated so much of Norway’s agricultural output, a country that was barely self-sufficient before the war suffered greatly under the occupation.

Lillehammer’s role was to serve for a brief time late in the war as the headquarters of the Nazi occupation in Norway. They relocated there from Oslo in late 1944 or early 1945. The hotel where we stopped for lunch and which is today a part of the Radisson Blu chain served as the Nazi headquarters in Lillehammer. Today, Lillehammer remains a relatively small, picturesque city with a population a bit more than 26,000.

We reached Oslo late in the afternoon and checked back into the same hotel we’d occupied a week earlier. Revisiting the Norwegian capital provided me the chance to make good on visiting three places I’d missed the first time around. The first was Vår Frelsers gravlund, the cemetery located a few kilometers north and west of the hotel where I sought and found the graves of Henrik Ibsen and Edvard Munch.

The second was to stop for a beer and a bite to eat at a spot recommended by Testudo Times reader nattyboandoldbay – the Crow Bar. Although the bartender in the picture is Australian, the place itself has neighborhood feel to it.

Now, we returned to Oslo on a Monday evening and, if you look at the lower right corner of the chalkboard menu, you’ll notice that you can order a six-pack sampler (0.2L each) of any of the 18 brews on the menu. In truth, neither the Hat nor I were overly impressed with the food (served upstairs from the bar) but after drinking over a liter of samplers and another 40 cl of the Bavarian Hefeweizen (#19) neither the Hat nor I cared very much about food quality.

My last stop was to see the Opera House that opened in 2007. As a group, we’d stopped there shortly after first arriving in Norway for a distant photo op but I decided not to get out in the rain that morning. The building is constructed of Italian marble and white granite meant to evoke an iceberg rising out of the water and the roof of the building angles to the ground allowing pedestrians to climb and traverse it which is a unique experience. Here are all of my photos from the last day in Oslo.

I chose to insert the photo below not because it captures the compelling beauty of the building but to permit to briefly don the linguistic version of my vest.

Notice that the building is called Operaen. Unlike English, Norwegian, like all the Scandinavian languages, has no definite article. What the Norwegians do is attach the indefinite article ‘en’ as a suffix. Thus, Operaen should be read as The Opera. So when you see the word Vøringfossen it refers to a specific waterfall. (This holds true unless the word is imported from German such as in the name of Norway’s second largest city, Bergen.)

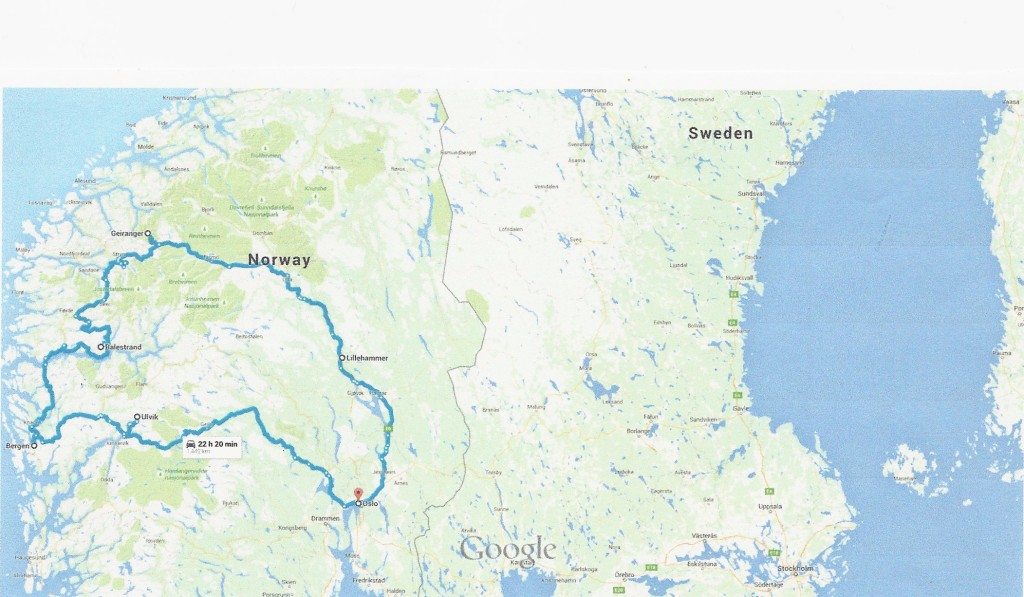

All that remains for me on this day is to wander back to the hotel to try to get some sleep. All that remains in the Norwegian leg of this year’s trip is to board the bus Tuesday morning and drive the 120 kilometers or so to the Swedish border. If you’ve been along for the entire length of this part of the journey, the blue line traces the route we’ve traveled in Norway:

It’s a substantial section of the country but we’ve sure missed a lot, too, haven’t we?