Hey, hey, hey, hey, hey! – part 2

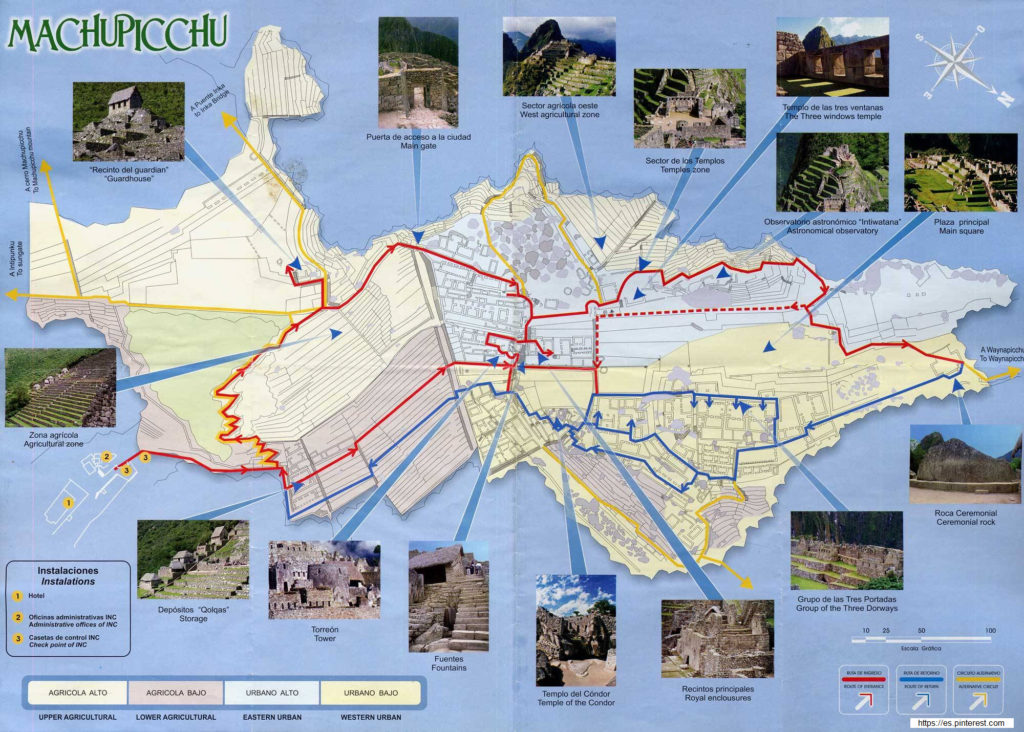

Before we set out, take a look at this map that shows the route we’ll take through the site.

(Although significant portions of the site have been restored, it has become such a high demand tourist attraction that the large number of visitors was beginning to degrade it. Thus, there is supposed to be a limit to the number of daily visitors permitted entry and the route we must follow – along the red line starting from number three and returning from the Ceremonial or Sacred Rock along one of the blue line routes – is fairly well circumscribed.)

A walk to remember.

Enough of my preambling, let’s start our walk through the archaeological site we call Machu Picchu. (For me, the walk was surprisingly easy. Before the trip I’d been a bit apprehensive about whether I’d fully enjoy our few hours at Machu Picchu or be distracted because of discomfort from its altitude at 2,400 meters above sea level. As it turned out, my apprehension had been unwarranted. What I’d failed to consider was that we’d have already spent 10 days at altitudes considerably above that (the 3,800 meters at Lake Titikaka or even the 3,400 meters at Cusco) so by the time we reached Machu Picchu my attitude was, “Twenty-four hundred meters. Bring it on. I’ve trained at altitude.”)

Note: I will be using the current descriptive terminology in writing about specific areas of the complex.

The Guardhouse.

The first stop on our route is near the crest of a winding ascent to the thatched roof building usually described as the Guardhouse though it’s sometimes called the Caretaker’s hut. The structure itself is open on one side.

(This photo was taken later in the day from the blue route but I’ve used it here to provide some perspective of the path up.)

It’s presumed to be a guardhouse because it oversees the site’s two main entrances – the southern trail from Inti Punku (The Sun Gate) and the western trail from Vilcabamba. (I took most of my broad view photos of Machu Picchu from here or somewhere along this upper level of the complex.)

We proceeded along a small portion of the trail coming from the direction of the Inti Punku

to the main gate.

By now you should be familiar with its trapezoidal shape though you might find its relatively small size somewhat surprising. You need to keep in mind that the site was not easily accessible and that the likely inhabitants were either workers, Inkan royalty and their visitors, or people such as priests and astronomers who were also among the elite of Inkan society so it’s unlikely to have needed to accommodate large processions.

(In the National Geographic article cited previously, Doctor Bauer also asserts that the Inkas weren’t the only culture living at Machu Picchu. He points to evidence on skeletons of varying kinds of head modeling – a practice we first encountered with the Tiwanaku civilization. Further evidence comes from the presence of ceramics found at the site that show characteristics associated with several different cultural traditions. He says, “All this suggests that many of the people who lived and died at Machu Picchu may have been from different areas of the empire.”)

The Rock Quarry.

Continuing our walk, we pass a quarry on our left. At first glance, it appears to be little more than a jumble of rocks.

(My photo doesn’t really do justice to the expanse of this section.)

However, it’s believed that some of the stones used to build Machu Picchu were quarried on the site and that rocks transported to the site were brought to this area indicating that this was also a workplace. Some of the rocks still look like they are in the process of being shaped and, if this is the case, their unfinished state would reinforce this notion. Whenever the Inkas needed to relocate a boulder – whether finished or unfinished – we have to assume it was done with sheer human force. They may have rolled the rocks over logs but the Inkas had neither the wheel nor any large draft animals. (Llamas could only carry a maximum of 20-25 kilograms.)

A new theory appeared a decade or so ago that posits Machu Picchu as a place that marked the end of a pilgrimage. This has led some to think that the quarry area is a representation of the Inkan creation myth. The “in process” appearance of some of the rocks makes this hypothesis a plausible interpretation. So, what was it’s purpose? In sum, “We don’t know.”

The Temple of the Sun.

Certainly, the most striking structure of the urban sector and perhaps one of its most important is the Temple of the Sun. Those who have seen the temple to Inti in Cusco will immediately see a connection between the two.

Since nearly every Inkan building was rectangular, structures with curved walls are particularly striking and noteworthy and, in this instance, there are clear echoes of the Sun Temple at Qorikancha.

The large stone slab may have been an altar of some sort but the window above it aligns with the sunrise on the winter solstice indicating that it was used not only to bring the Inka closer to the sun – it’s believed they saw this as essential to their spirituality – but that it had a practical astronomical function. Another indication of its importance is that the access gate had double locking beams. These are evident in the way the stone of the doorway is carved.

The Royal Tomb.

Directly below the Temple of the Sun lies a natural cave. In his early explorations, Bingham referred to it as the “Royal Mausoleum.” This description is generally disputed because there’s little evidence that the cave was used in that way.

Both its location and the clearly deliberate carving of the stairway shape of the front boulder indicate that it had some formal use but that use was probably ceremonial rather than funereal.

There was, at one time, a belief that Pachakutiq was buried at Machu Picchu but that would have been out of keeping with interring the mummy of every Sapa Inka at Qorikancha. The theory of Pachakutiq’s burial at Machu Picchu (though not at this spot) had a revival when a French Engineer named David Crespy noticed what he called a hidden door. The spot was then examined by Thierry Jamin and the Instituto Inkari NGO confirming not only the door but a hidden chamber concealed behind the walls was revealed by electromagnetic equipment. To date, the Peruvian government has refused them permission to excavate.

I’ll break here and we’ll finish our walk through Machu Picchu in the next post. (And by the way, the title of this post is a hint to the title of the next one.)

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026