(Delgadillo’s) Diner over on the edge of town.

As I mentioned previously, I started feeling hungry while I was hanging with the animals but with good reason. I’d been keeping myself to a mainly liquid diet of iced tea and water supplemented by a handful of nuts every now and then because I wanted to eat lunch about 60 miles farther east in Seligman. That’s where you can find two of the most noteworthy spots on this stretch of Historic 66. I’d planned for one but opted for the other based on the recommendation of the woman at the information center in Kingman. More on that after this brief message from our sponsor, Burma Shave.

In 1926, a series of three signs appeared on the roadside of Highway 65 near Lakeville, Minnesota. They read, “Cheer up, face – the war is over! – Burma-Shave.” Before long, the series of red and white signs with clever rhymes began popping up on roadsides around the country. At first, the signs were pure advertising but in 1935 the first road safety signs appeared:

Train approaching / Whistle squealing / Stop / Avoid that run-down feeling / Burma-Shave

This type of sign began to appear more frequently by 1939. Today, if you drive stretches of Historic 66, particularly between Valentine and Seligman, you will, with some touch of irony, see reproductions of those signs.

(You can see the end of the rhyme in this photos folder.) The irony is that, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, the original Burma Shave signs never adorned Route 66.

You remember Seligman, right? It was the home of Angel Delgadillo the barber who organized the Historic Route 66 Association of Arizona in 1987. Thus, it’s with pride that the town boldly asserts its status.

Approaching from the west, I reached the first of the two restaurants I mentioned above. The woman in Kingman told me this would be a fine place to stop but that I’d probably have more fun at the second. Still, it’s worth a photo just to show that there really is at least one

Roadkill Cafe.

The second Seligman landmark eatery was owned by Angel’s brother Juan Delgadillo. It’s called Delgadillo’s Sno-Cap Drive In. First built in 1953, it has now earned a spot as a Route 66 Roadside Attraction. If the “dead chicken” sign isn’t enough of a hint, take a close look at the photo below (pay special attention to the door) and you’ll get some idea what you’re in for if you stop here.

The item on the menu, which includes such items as the Bob Dog (short and fat 6″) and the John Dog (long and thin 12″), that caught my eye was the Girl Cheese. I asked the girl who took my order if I could eat a Girl Cheese and she told me I should try it only if I thought I was man enough. Challenge accepted and overcome – with an order of fries to boot!

Roughly 18 miles east of Seligman near Ash Fork, Historic 66 rejoins I-40 and, as you drive toward Williams, the two are one and the same. Although many of the 250 miles of Route 66 in Arizona are chopped and broken, but the time I rejoined I-40 at Ash Fork, I’d driven about 136 miles of the long unbroken strand of 158 miles between Ash Fork and Needles.

At that point the day was still young enough that I thought it too early to return to Williams. Believing I had time to take in one more attraction, I barreled past the Williams exits and continued east for another 70 miles or so. Along the way, I passed the sign in the picture below and had to take a photo of it because the song tells me not to forget it.

(This, by the way, is another place where Troup twists his geography. Traveling west from Chicago you pass Winona before you reach Flagstaff.)

That weren’t no d.j. that was hazy cosmic jive.

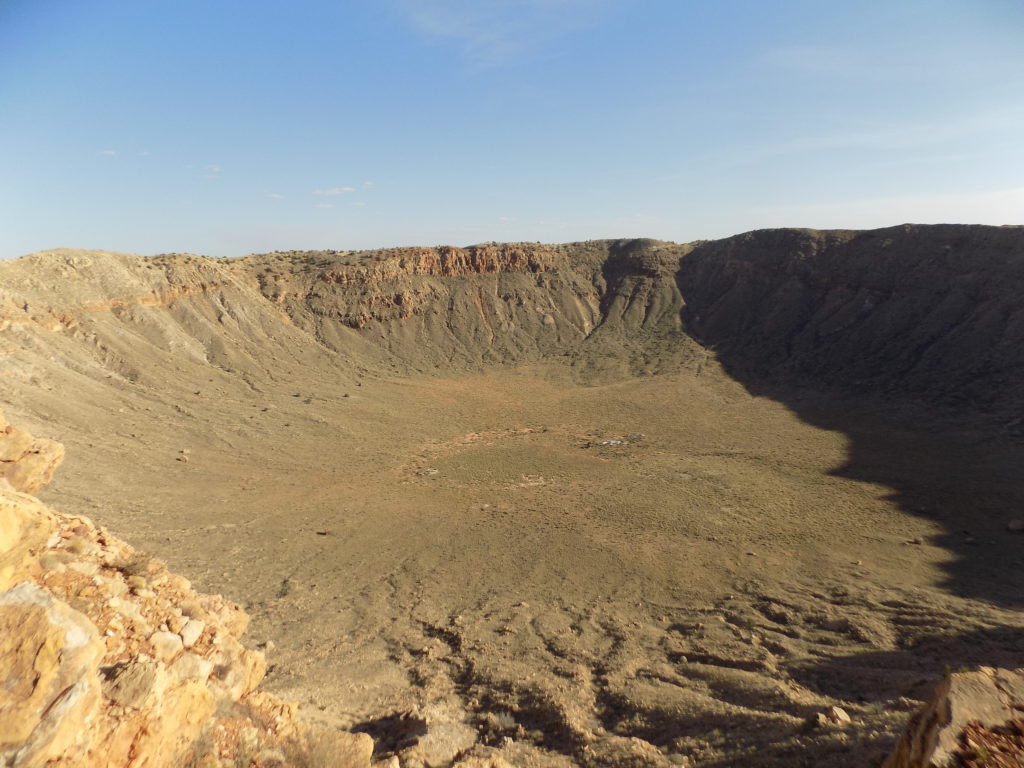

The target of my hurried drive had made my list of places to see because of its association with a movie. As it turns out, it was visually inspiring and scientifically interesting enough that it belonged on the list regardless. The site is known and promoted as Meteor Crater but in the scientific community it’s referred to as Barringer Crater in honor of Daniel Barringer – the eventual owner of the property and the geologist who published the first paper hypothesizing that this was an impact crater and not, as all terrestrial craters were believed to be at the time, created by explosive or volcanic venting.

The story I’ll tell you about the crater begins in 1891 when G. K. Gilbert, the chief geologist at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) examined the Arizona crater and declared that it had, indeed, been created by an explosive venting of volcanic steam. Behaving non-scientifically, Gilbert, rather than seeking an explanation for data that countered his preconceived notion, willfully ignored the clear presence of thousands of small meteorites in the crater’s vicinity and thus conformed the data to fit his hypothesis.

At about the same time or perhaps as much as a decade later (historical accounts conflict) Barringer heard of the crater and set about attempting to prove that it was, indeed, an impact crater caused by a meteorite. Having seen and heard about the iron particles at the crater, he also saw it as a commercial opportunity which prompted him to purchase the crater and much of the surrounding land. He mined the crater for several decades without ever finding the significant meteor remnant or extracting as much iron as he’d hoped and lost more than $500,000 in the process.

However, he also continued in his assertion that the crater was a meteor impact crater. In 1906, Barringer and his partner, Benjamin Tilghman, presented their first paper to the U.S. Geological Survey outlining the evidence in support of the impact theory and the paper was published in the Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences. While the paper convinced a handful of geologists and, although Barringer continued to try to persuade the scientific community that his impact theory was correct until his death in 1929, Gilbert’s position generally held the day.

That all changed with the arrival of Eugene Shoemaker in 1960. Shoemaker, who may be best known for discovering the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 with his wife Carolyn and their colleague David Levy, came to Barringer Crater and to the Nevada atomic bomb test site at Yucca Flat while working on his Ph. D. at Princeton.

Shoemaker was studying the dynamics of impact craters. In the course of his examinations at Yucca Flat, he found a rare form of quartz called coesite that has a microscopically unique structure caused by intense pressure. When he found the same quartz at the Meteor Crater site, he was able to seek additional evidence that ultimately proved Barringer right. Shoemaker’s work provided the first scientific proof that impact craters did, indeed, exist on earth. So now, Meteor Crater, historically significant without hyperbole, bills itself as world’s best preserved meteorite impact site on Earth.

I’ll have a few more facts about the crater in the day’s final post.