Goin’ places that I’ve never been.

According to the website of the National Historic Route 66 Association, one can drive on approximately 85 percent of the road’s remnants but you have to look for them. You can find about 250 of those miles in Arizona and today was my day to explore some of those miles – in the way you’d probably expect of me.

That is, I started the day by not starting the day on Route 66 or, at least not obviously being on 66. It’s likely that the section of I-40 between Williams and Ash City was or lies over a portion of the mother road. However, I continued along I-40 for more than 110 miles eventually connecting to Arizona 68 to drive to Bullhead City.

Going to Bullhead City broke a bit of a pattern for me. Those of you who have followed my past travels might recall that I celebrate moments when I unexpectedly encounter turtles. My decision to visit Bullhead City was to affect a deliberate turtle moment.

I’m not certain about Poki’s full history. I know that it was originally commissioned by a Bullhead City resident named Bill Hayes who kept it on his property until he moved to Montana in 2013 when he decided he couldn’t take the “realistic but friendly looking” two-ton Poki with him. He donated it to the town. Poki now greets visitors to the Bullhead City Chamber of Commerce.

If you look closely beyond the cactus sculpture to Poki’s left, you can see a spot of blue between the two strips of brown. That, my friends, is the Colorado river. The brown hills on the far side of the river are in Nevada. In fact, if you cross the river, you enter the casino laden town of Laughlin. And that’s precisely what I did. Why, you wonder? The simple reason was that it presented an opportunity to add to my collection of “Welcome To” signs. You see, although I’ve now visited (or by the end of this trip will have visited) 47 of the 50 American states, I only have photos of the road welcome signs from 25 of them plus the odd sign from Louisiana. Nevada is no longer among the missing.

I feel compelled to share that on the way to Bullhead City, I passed this quite interesting rock formation on road 68:

Indeed, the locals call it Finger Rock. And, who knows, perhaps it’s making an expressive gesture on behalf of all the Arizonans who left Laughlin poorer than they’d arrived.

Preparing to leave Bullhead City, I had a choice. I could follow Arizona 95 for 23 miles south to Needles – the point where Route 66 entered California – (and add California to my “Welcome To” collection) then follow the historic path of 66 down to Topock (36 miles), back north to Oatman (57 miles), and then on to Kingman (36 miles) where I’d start my journey back toward Williams on Historic Route 66. Or I could simply retrace my journey on Arizona 68 thereby saving 120 miles and two hours of driving.

Since my intent wasn’t to make the trip exclusively about Route 66 but wanting to get a feel for the real experience, I opted for a third alternative that was about 10 miles longer than the direct route. I took Arizona 95 south to Silver Creek Road which becomes County Road 10 (Oatman Road) and is a remnant of Route 66.

Although I was tempted to stop in the Dollar Bill Bar where patrons sign and date dollar bills and tape them to the walls, it was enough of a detour that I decided to bypass Oatman. There’s really not a lot to see here. This stretch of the road is your basic two-lane highway crossing relatively barren terrain in a somewhat serpentine manner. As I approached Kingman, I passed Crazy Fred’s Whorehouse Truck Stop (Really!), which I would have missed had I used 68, and entered Kingman on the stretch of Historic 66 called Andy Devine Avenue.

(For the young pups among you, Andy Devine was a character actor who appeared in nearly 200 movies and television shows – including John Ford’s 1939 classic Stagecoach – in a career that stretched from 1926 until his death in 1977. Devine was born in Flagstaff but grew up in Kingman and is probably the town’s most famous resident.)

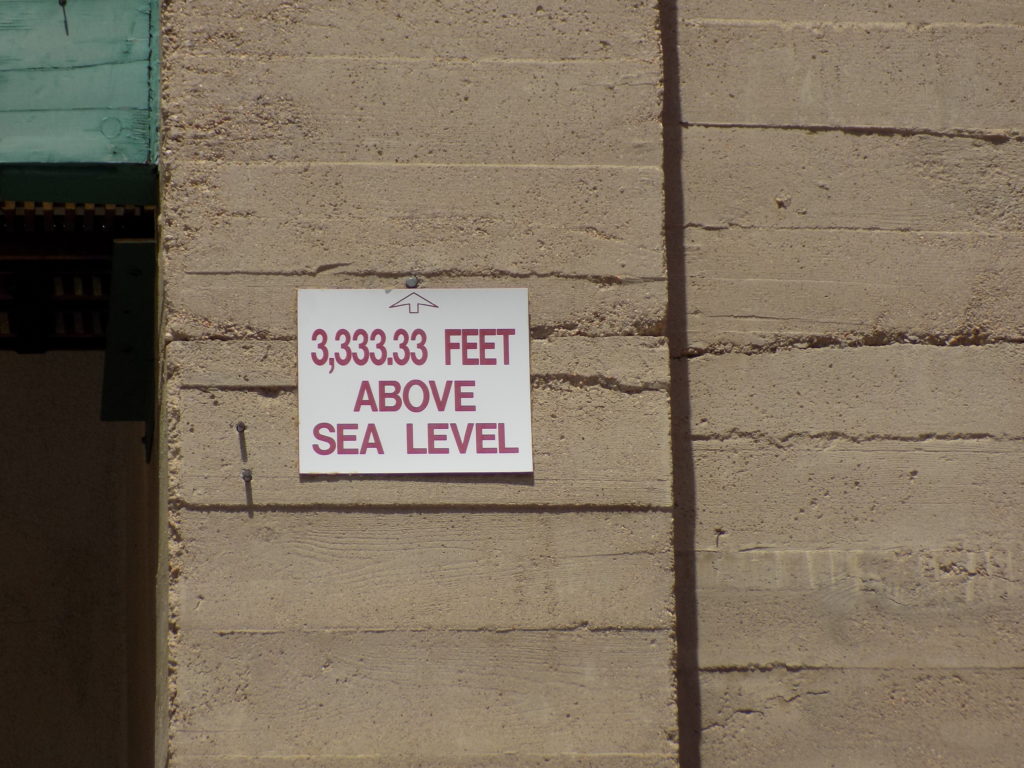

I stopped in the Arizona (Powerhouse) Route 66 Museum which has this rather curious sign by the door.

The woman at the help desk answered several questions I had and was, indeed, helpful. I quickly walked through the free area but elected not to spend any significant time in the museum because I was only minimally interested in its collection and I had a full agenda aHEAD of me.

Just as far and as fast as I can, uh huh.

Yes, this

is a real thing. After passing the water tower that welcomes the route’s westbound travelers to Kingman, I began the journey 30 miles east to Walapai (sometimes Hualapi) for what I considered my first real photo op on Historic 66 – the Giganticus Headicus.

Created in 2004 by Gregg Arnold, a transplant from New Jersey, this object is a 14-foot-tall Easter Island type head sculpted of metal, wood, chicken wire, Styrofoam, and cement painted an unusual shade of green. Arnold has other works adjacent to the featured one and you can see photos of most of them in this folder.

As became my practice whenever I stopped for these free photo ops, I made a small purchase in the adjoining shop. (In this case, a new black straw hat and a bottle of water.) I also put a pin in their wall map so they’d know they had at least one visitor from Silver Spring.

But I wanna know for sure.

Next stop, Valentine. Twelve or fifteen miles east of the Giganticus Headicus there’s a wildlife sanctuary called Keepers of the Wild. Their sponsorship brochure describes their mission as

A place where exotic animals find a lifetime home, free to run and play. Free from hunger abuse and neglect. Free to live their lives without breeding.

One way they carry-out their mission is through an

ANIMAL RESCUE PROGRAM:

We collaborate with and provide rescue services to:

1.) Local, State, National and International Law Enforcement & Animal Welfare Agencies who confiscate exotic animals from illegal or abusive situations.

2.) Private owners that come to the realization that exotic animals are not pets.

They go on to say, “many of our animals were acquired from the private sector and entertainment industry, we have a strong focus on preventative measures.”

Even more nobly, the organization commits itself to providing lifetime care for the rescued animals.

LONG-TERM ANIMAL CARE PROGRAM:

Our Animal Care Program includes all expenses associated with providing long-term care for our animals. Care expenses including food, supplies, veterinary care, enrichment, staff, habitat maintenance and new habitat construction.

We currently provide care to over 150 animals, of which 40 are classified as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. These animals include a jaguar, lion, tigers, leopards, cougars, primates, wallabies, wolves , reptiles, birds, hoof stock and a variety of indigenous wildlife. Most have been neglected, abandoned or abused and are therefore allowed to live out the rest of their lives being well cared for.

It all seemed so right. Yet somehow, I walked away thinking some things were simply wrong. Clearly the caretakers and volunteers cared deeply for the animals and their welfare. Their hearts and intentions all seemed to be in the right place.

And I had only a little doubt that these animals had better lives than the ones from which they’d been rescued. Whether any of them had been psychologically abused, it was clear both from talking to the people there and from simple observation that some of the animals had survived physical abuse. And yet, still, something felt wrong.

Perhaps I was hot – the day certainly was – and many of the animals were wisely doing what they could to find shade and relief.

Perhaps my reaction came because I was hungry and moving toward my typical hunger induced crankiness but I think it was more than that. I think my disquiet had something to do with the environment – this photo of Route 66 a bit east of the park is representative –

and seeing so many species such as the alpacas and llamas, arctic wolves, and capuchin monkeys (to name a few) that simply don’t belong in this type of climate or environment. Or seeing the lone capybara – a species known for being highly social in the wild – that made things feel disharmonious to me. And, of course, my sense of dissonance wasn’t helped by the fact that their “habitat” is mainly a fenced area albeit – with some room to move about and some features that could be considered enriching.

I tried to believe that the sanctuary provided by Keepers of the Wild was probably the last best hope for these animals and yet, I couldn’t help but believe that on some level they deserved more. It just didn’t seem like a very happy life.