The language map I used to guide my exploration of First Nations in Canada, once again proved helpful as I turned my attention to earliest humans to inhabit the southeastern United States. Their languages belong to a group identified as Muskogean with an intriguing pocket of Iroquoian attached to the northeast corner of their range. It’s not my purpose to take a deep dive into whether this indicates a common ancestor for these groups but Sean P Harvey wrote in a 2018 article for the William and Mary Quarterly,

Early nineteenth-century Delaware, Haudenosaunee, Cherokee, Creek, and diverse Central Algonquian accounts show that sometimes Native speakers pointed to language as indicative of shared ancestry; at other moments, however, they perceived it as merely a medium of communication subject to present relationships. Ultimately, groups and individuals could use shared speech, varying intelligibility, or utter difference to draw inclusive or exclusive kinship lines for strategic purposes that included either ethnic demarcation or alliance building among peoples.

Ample evidence supports the conclusion that people first reached the southeastern part of the American continent at least 12,000 years ago and likely as long as 14,500 years BP. These earliest artifacts together with animal bones were found at a site called Page-Ladson in the Florida panhandle less than forty miles southeast of Tallahassee.

In fact, in the last years of the twentieth century, excavations at the site yielded eight lithic artifacts associated with mastodon butchering and that were dated to approximately 14,400 BP. This predates the Clovis site in New Mexico by two millennia and makes it the oldest known site east of the Mississippi River.

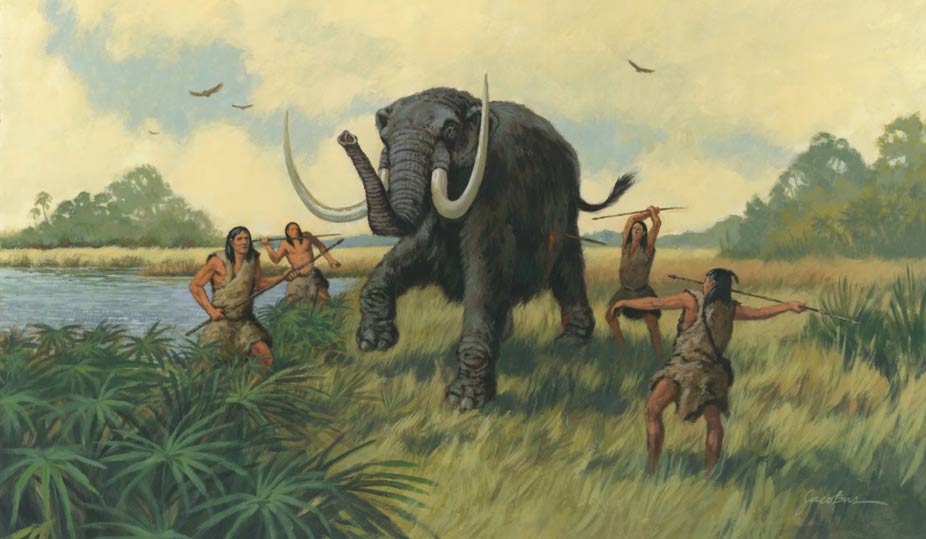

These humans hunted mammoth in the late Pleistocene and early Holocene eras

[Image from ancientorigins.]

– a time spanning at least 2,000 years thus undermining another long held belief that humans quickly hunted the mammoths into extinction. Regarding the age of the site, Michael Waters, the director of Texas A & M University’s Center for the study of First Americans stated in a 2016 article on phys.org,

“The stone tools and faunal remains at the site show that at 14,550 years ago, people knew how to find game, fresh water and material for making tools. These people were well-adapted to this environment. The site is a slam-dunk pre-Clovis site with unequivocal artifacts, clear stratigraphy and thorough dating.”

Current evidence points to the earliest Native Americans remaining in the extreme southeast for several millennia before they moved northward into Georgia about 10,000 years BP. More precise dates are difficult to cite because they appear to have used tools and a strategy of mobility that, while well suited to the early Holocene environment, left behind scant evidence for 21st century archaeologists. They do not appear to have had a significant agricultural program nor did they construct more permanent villages.

These early Paleo and Archaic natives seemed to have fared well for thousands of years with little encroachment on their territory. However, perhaps as early as the ninth century CE they were replaced by eastward migrating (or territorially expanding) tribes of the Mississippian culture who were the first in the region to farm on any significant scale cultivating maize, squash, and numerous types of beans.

Tribes of the Mississippian culture lived in large towns that were often fortified and housed thousands of families. Another dominant feature of this group is that they were mound builders. The earliest known example is the mound at Ocmulgee with a more famous complex at Etowah.

[Photo from Trip Advisor.]

This has led some archaeologists to speculate that these early inhabitants were from the same group that built the famous complex at Cahokia. (Those of you who have been following these posts for years might recall the fascination I developed for the mound building cultures on my 2014 trip along the Great River Road.) Others have hypothesized that these natives originated in Mexico.

Gary C Daniels explains the basis for this in an article on the site LostWorlds.org where he writes,

…the Cussitaw (Cusseta/Kasihta), have a migration legend which might relate to the settlement of Ocmulgee Mounds. It tells how they originated in a place much farther west, a place where the earth would occasionally open up and swallow their children (a possible reference to earthquakes). Part of their tribe decided to leave this place and began an eastward migration in order to find where the sun rose. On their journey they came to a mountain that thundered and had red smoke coming from its summit which they later discovered was actually fire (a possible reference to a volcano.) Here they decided to settle down after meeting people from three nations (Chickasaws, Atilamas, & Obikaws) who taught them about herbs and “many other things.”

From these references one can speculate that these people migrated from Mexico which is west of Georgia and has both earthquakes and active volcanoes. (For a more in-depth analysis of the Creek migration legend, read “Were Georgia’s Muskogee Creek Indians from West Mexico?“) Mexico is also the birthplace of corn agriculture, a defining characteristic of these newcomers. It is also in Mexico where we find cities consisting of flat-topped pyramid mounds arranged around open plazas which is the most noticeable feature of town planning at Ocmulgee.

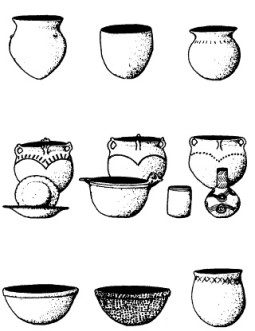

The first truly Mississippian town in the southwestern part of Georgia appears at a site called Cool Branch a little south of Columbus and dates to about 1100 CE. Trying to determine whether this town appeared as a result of a natural cultural evolution or because of some sort of invasion, a pair of researchers examined three distinct pottery styles called Averett from the north near Columbus, Wakulla which was dominant in the south near the confluence of the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers, and Rood a distinctly Mississippian style found mainly between the other two.

[Averett (top), Rood (middle), and Wakulla (bottom) pottery. (c) 2002 From lostworlds.org.]

The fact that the Rood style pottery simply showed up suddenly around 1100 CE seems to support the invasion hypothesis. By 1300 CE, the Averett style disappears from the archaeological record while the Wakulla culture assimilated the Mississippian into its own hybrid. Over the next century, the Rood style of pottery disappeared and, in a demonstration of the principle that it’s often easier to conquer territory than it is to hold it, the Wakulla regained control of their traditional territory ultimately outlasting the invaders from the west.

However, in another century or so, the natives would face a different form of invasion – this one coming from the east. I’ll talk about the arrival of Hernando de Soto and James Oglethorpe in the third and final supplement.