One of the aspects of Stockholm I found so appealing was the abundance of preserved buildings. Though you see many Neoclassical buildings from the 19th century, Stockholm retains a broad range of architecture from with structures ranging from the late Renaissance to Art Nouveau. Like many Nordic people, Swedes see great value in preserving and reusing as many of their assets as possible so they are inclined to preserve and restore rather than raze and replace. Sweden also has the advantage of practicing studied neutrality from early in the 19th century and this kept Stockholm free from much of the destruction that would be visited in other European cities particularly in the two great western wars of the 20th century.

The Finns have perhaps an even stronger preservationist world view. Thus, Helsinki, while not quite as fortunate with regard to avoiding martial destruction, still manages to preserve many of its Neoclassical and Art Nouveau structures.

The Finnish capital was bombed on eight separate occasions during the Winter War with the Soviet Union. In these raids, more than 50 buildings were destroyed and nearly 100 people killed. Prior to the three great bombing raids in February 1944, the city was bombed 39 times during the Continuation War. Although during the Winter War the American President Franklin Roosevelt had somewhat futilely asked the Soviets not to bomb Finnish cities, by the time of the great raids, Stalin had gained approval from the Americans and the British to launch bombing raids. The stated Soviet intention was that these raids would cause Finland to sever its ties with Germany.

The first in the series of two-night raids took place on 6 and 7 February. The second followed 10 nights lighter and the third came after another 10 nights had passed. The Finnish Army estimated that over 2,000 bombers took part in the three raids and dropped more than 16,000 bombs containing about 2,600 tons of explosives. However, the damage to Helsinki was relatively minimal. Of the 16,000 bombs only about 800 fell within the city, and some of these fell in uninhabited park areas causing no damage to structures.

The official death toll was 146 people with another 356 wounded. The bombs destroyed 109 buildings and damaged another 300 including, ironically enough, the Soviet Embassy. This combination of the Nordic ethos and relatively limited damage has allowed Helsinki to retain much of the character and architecture it might have had through the 19th and early 20th centuries as it grew into its role replacing Turku as Finland’s capital and largest city.

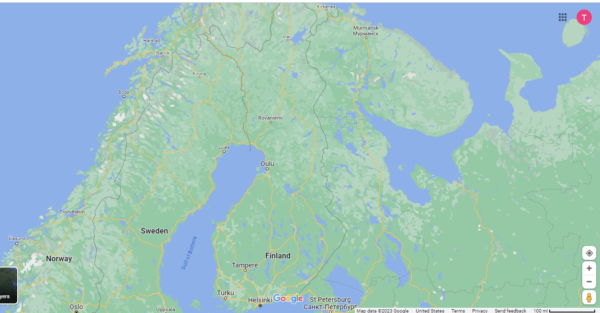

If you look at this screenshot map of Finland, you’ll find Turku in the nation’s southwest corner about 170 kilometers west of Helsinki.

In its earliest settlements, the spot likely served as a market place during the 13th century but was more formally established as a city when its cathedral was consecrated in 1300. Conveniently located about as close to Sweden as any point in southern Finland, and remember the Swedes controlled Finland for the better part of seven centuries, Turku quickly became the most populous city in Finland in addition to being it’s most important cultural and trading center as well as the de facto capital.

After Sweden ceded the territory of Finland to the Russian Empire in 1809, (via the Treaty of Fredrikshamn) Turku became the official capital of the Grand Duchy of Finland. It didn’t retain that status for long, though. Alexander I looked at Turku and seems to have had a thought along the lines of, “Turku. Too close to Sweden. Too far from Russia,” and by 1812 he had relocated the capital to Helsinki – a city he and his successor, Alexander II, would build up very much in St. Petersburg’s image over the ensuing century or so. This influence is dramatically evident in the city center and around the Senate Square with its cohesive Neoclassical architecture.

Alexander II, whose statue stands in the Senate Square in Helsinki,

is something of a hero to the Finns and, had he not been assassinated in March 1881, might hold a similar place in the hearts of the Russian people. Alexander II was 37 when he succeeded his father in 1855. During the first year of his reign, Russia suffered a somewhat humiliating defeat in the Crimean War that ended with the 1856 Treaty of Paris in which the Russians ceded significant territory to the Ottoman Empire.

Alexander began to implement a series of radical reforms that included an attempt to not depend on a landed aristocracy controlling the poor, a move to developing Russia’s natural resources, and a reformation of all branches of the administration. In 1867 he completed a transaction of importance in American history. Still feeling the sting of the losses sustained in the Crimean War and fearful that he might lose more territory in a war with Britain, Alexander completed negotiations with Secretary of State William Seward for the sale of Alaska to the United States for a bit more than seven cents an acre.

Alexander was pressing other reforms in Russia and had a similarly tolerant view of relations with the Grand Duchy of Finland. Unlike the Swedes, Alexander not only didn’t impose the Russian language on the Finns, he elevated Finnish to the status of an official native language. (Although only about five percent of Finns speak Swedish as their first language and they are mostly in the southwest near Turku, Swedish remains an official language in Finland.) He also allowed the Finns to have their own currency as well as their own Diet (or Parliament). This autonomy laid much of the groundwork for Finland’s ultimate independence in 1918. Thus, despite the fact that he headed the government of an occupying power, after Alexander II was assassinated in St. Petersburg in 1881, the Finns thought enough of him to honor him with the statue seen above in the city’s main square.

It’s finally time to end this part of the history lesson. The Senate Square was, in fact, the last stop on our tour but I jumped ahead in our sightseeing to discuss Alexander II because of his historical importance.

I’ll provide more of a look around Helsinki in part two.