We were still crossing the Baltic Sea when I ended the previous post with Finland holding its first local elections between 17 and 28 December 1918. But the Finns weren’t quite done with the electoral process. So, let’s pick up the story from there.

They held their first parliamentary election in March 1919 and ratified their Constitution on 17 July. Eight days later Finland elected its first president. But many wounds from the Civil War remained open. Some 36,000 people, more than one percent of the country’s population at the time, died in that war and many were due to acts of terror and assassination carried out by both sides. The Civil War left upwards of 15,000 children orphaned. The war had deeply gashed the fabric of Finnish society and much work remained to stitch it back together.

Ultimately, the weakness of both Germany and Russia after World War I empowered Finland to act in its perceived best interests and, bolstered by the cultural ethos of the Finnish people, they reached a peaceful, domestic Finnish social and political compromise settlement. This reconciliation led to a slow and painful, but steady, national unification.

Even as this internal reconciliation took place, some work remained to finalize the border between Finland and Russia. The Finns and the Russians wrapped up this bit of business in October 1920 when they signed the Treaty of Tartu. The treaty confirmed the border between Finland and Soviet Russia and established the boundaries of the nation that would be drawn on twentieth century maps until the end of World War II.

The Finns and World War II

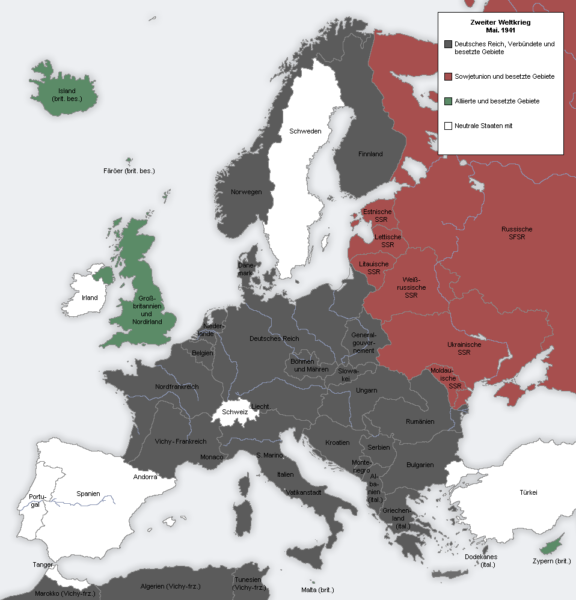

Finland’s involvement in the second world war transpired in what the Finns see as three main phases – the Winter War (1939-1940), the Continuation War (1941-1944), and the Lapland War (1944-1945). The Moscow Treaty of 1940 ended the Winter War but the terms, which included ceding nearly all of Finnish Karelia in the south and parts of Salla in the northeast, were so harsh that they quite likely gave rise to the circumstances that set the stage for the Continuation War.

The Winter War started in 1939 with a Soviet invasion that initially had the look of a border skirmish but that concealed a deeper intention. The Soviets intended to cut Finland in half and capture both Petsamo in the north and Helsinki in the south. The powers of the world applauded the tenacity of the outgunned and undermanned Finns but did little to help them in any material sense. The Finns eventually lost the ability to withstand the greater forces of their much larger, richer, and more powerful neighbor and, under duress, signed the Treaty of Moscow granting the Soviets even more territory and sovereignty than they had initially sought.

Still fearing additional aggression by the Soviet Union, the Finns sought to make defensive arrangements with Great Britain and Sweden but when these efforts proved fruitless, Finland turned to Germany for military aid. The Germans were preparing to launch their attack on Russia known as Operation Barbarossa. This set of negotiations allowed German troops to establish positions in Finland as they had done once before.

[Map by DIREKTOR at en.wikipedia. – From en.wikipedia to Commons., CC BY-SA 3.0.]

Three days after the beginning of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941, the Soviets launched massive bombing raids against Finland leading the Finns to declare war on the Soviet Union. This became known as the Continuation War. Like much of the history I’ve skimmed over here, what transpired during the Continuation War is far more complex than I can explain with any semblance of brevity (a phase rarely attached to any of my writing).

The big picture has the Finns on the offensive early in 1941 and regaining much of the territory they’d lost in the Winter War. There was something of a three-year lull before the Red Army launched a major offensive in late June 1944 that more or less pushed the Finns back to the 1940 positions. The situation had become so bad that Risto Ryti, the president of Finland, promised Nazi Germany that they would not negotiate a peace treaty with the Soviets.

This promise led the Germans to ship arms to the Finnish Army allowing them to halt the Soviet advance. With that accomplished, Ryti resigned his presidency. The Finnish Parliament appointed a new president and charged him with negotiating peace with the Soviet Union beginning with a cease fire agreement. This was sufficient for the Soviet Army and political leadership at the time because they had a more pressing focus. The success of the invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944 saw British and American troops advancing apace toward Berlin and the Soviets wanted to reach the German capital before the western allies.

Somewhat ironically the foes in the final phase, the Lapland War, were the erstwhile allies Finland and Germany.

[Lapland War – Image from War History Online.]

The cease fire between the Finns and the Soviet Union required the Finns to break diplomatic ties with Germany and publicly demand the withdrawal of all German troops from Finland by 15 September 1944. The Germans were none too happy about this as they had a strong strategic interest in the nickel mines near Petsamo.

On the other side, the Soviets were none too happy with the passive manner the Finns had adopted in urging the German retreat. Goaded by the Soviets, the Finns became more forceful and the Germans, did in fact, retreat into Norway while laying waste to most of northern Finland on their way.

The concessions of the 1940 treaty together with some others were formalized in a second armistice with Moscow in 1944 and again in the final peace accord signed in 1947. These made permanent the changes in the border between Finland and the Soviet Union.

Still, through all of this, by the end of 1945, Finland was the only European country that shared a border with the Soviet Union that was not occupied. Through the course of the war, only three European capitals were never occupied by outside forces: Moscow, London, and Helsinki. Finland was the only co-belligerent of Nazi Germany that maintained democracy throughout the war and, despite its union of convenience with Germany, perhaps because Finland never signed the Tripartite Pact, it also managed to keep almost all its native Jews and refugees safe.

Now that you know a little bit about Finland, imagine me looking out the starboard side of the ship as we pass the island fortress of Suomenlinna (originally built on six islands in the middle of the 18th century by the Swedes) – a UNESCO World Heritage Site – that guards the seaward access to the city of Helsinki where we will shortly dock and I’ll spend an all too brief visit in Finland’s beautiful capital city. That visit will be the subject of my next posts.