Feeling sLOVEnia – part 1

Thus far on our trip around the Balkan Peninsula the countries we’ve visited have had long, troubled, and war-ravaged histories standing in sharp contrast to both the natural beauty of the territory and some of the stories of cooperation and coexistence we’d heard. And these contrasts certainly supported the purported etymology of the peninsula’s name. Our group leader Damir recounted this story to us early in our visit.

We know that the peninsula was long a part of the Turkish Ottoman Empire. Now, unite the Turkish words for honey (bal) and blood (kan) and Balkan becomes the land of honey and blood. In fact, some of you might even remember that Angelina Jolie wrote and directed a movie about the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina

with an image that evokes the Sarajevo roses and whose title appears drawn from this notion of the┬Āetymology of the word Balkan. While this seems both appropriate and somehow poetic, it doesn’t appear to be true.

Most dictionaries state that the region takes its name from a mountain range in Bulgaria called Balkan and that, while the word itself does indeed stem from Turkish, it’s more likely source is a word meaning “a chain of wooded mountains.” The first use of the term in English comes from the end of the 18th century by an Englishman named John Merritt. Soon thereafter other writers started applying the name to the area between the Adriatic and Black Seas and the idea of the “Balkan Peninsula” was created by the German geographer August Zeune in 1808. Still, it is nice to hold onto the notion that if our time in Bosnia and Herzegovina had exposed us to the kan of the story, our stay in the small but beautiful country of Slovenia would be the soothing bal.

Slovenia is the smallest of the former Yugoslav republics that is now an independent nation. (The newly formed country of Kosovo which, as of this writing, is recognized by 24 of 28 NATO nations, 23 of 28 EU member states and only 109 of 193 UN members was a region of Serbia and not a Yugoslav republic.) At a bit over 20,250 square kilometers it is about the size of New Jersey and, according to Damir, 153rd in size of the current complement of 193 UN member states.

More than half of the country is covered in beech, beech-fir, and beech-oak forests making it the third most forested country in Europe behind just Finland and Sweden. Slovenia is also quite hilly with more than 90 percent of its land 200 meters or higher above sea level. The tallest peak is Mount Triglav which rises 2,864 meters above sea level.

Damir also often liked describing the countries by analogizing them to a recognizable object. You might recall his characterization of Croatia as a boomerang and B&H as a triangle. Here’s a map of Slovenia:

To Damir, it looks like a chicken. I’ll leave the accuracy of his analogy to you.

To Damir, it looks like a chicken. I’ll leave the accuracy of his analogy to you.

Our route from Opatija would be fairly direct. We’d travel north and cross the border at Rupa (look down from the ‘O’ in Slovenia) then turn a touch to the east across the Karst Plateau to Postojna before our afternoon arrival in the capital Ljubljana. (Here, I’ll digress to thank Pat whose tongue-in-cheek pronunciation ‘le-jub-le-jah-nah’ – the correct formal pronunciation is the tongue twisting ‘lyu-bli-yah-nah’ – gives me the perfect mnemonic to spell it correctly.)

Above, I wrote that Slovenia, would be the metaphorical honey of the trip. Historically, it’s the most stable of the six former Yugoslav republics. Yes, the area was part of the Roman Empire and evidence indicates that the first Slavic tribes came to the territory in the middle of the sixth century. But by the 14th century, the area was taken over by the Hapsburgs and, other than a short five-year span, it remained part of Austro-Hungary until the end of the First World War when it became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia).

Because of this period of long stability under one ruler, Slovenia was as close to monolithic as any of the Balkan nations with 97 percent of the population declaring themselves as Catholic┬Ābefore World War II. However, this didn’t insulate┬ĀSlovenia┬Āfrom the impacts of the war during which time the country was divided between Italian, German, and Hungarian domination. With the liberation by the Partisans, Slovenia once again became part of Yugoslavia.

In 1987, an article calling for Slovenian independence appeared in the magazine Nova revija (New Journal) and by 1989 local legislators had amended the republic’s constitution to introduce a form of parliamentary democracy. On 23 December 1990, the republic became the first to hold an independence referendum. It passed with 88 percent of the vote.

Slovenia declared its independence on 25 June 1991. It was followed by a brief Ten-Day-War between the Slovenian Territorial Defense forces and the Yugoslav People’s Army controlled by Slobodan Milo┼Īevi─ć. The brevity of the war meant few casualties┬Ā– the Slovenians claimed 18 killed and 182 wounded – and only limited property damage. The European Union recognized Slovenia as an independent state on 15 January 1992 and the United Nations accepted it as a member barely four months later. Slovenia gained EU membership in 2004.

A word about today’s title.

The appearance of this entry’s title, “Feeling sLOVEnia” is not a typographical error. It’s actually a recognition of a clever marketing campaign that takes advantage of the fact that it’s the only country that has the word love contained within its very name. Shortly after crossing the border, you’re likely to encounter some variation of this sign

and now, I’ll bet you’ll never again see the name Slovenia the way you did before.

Lessons in geography and geology.

Our first stop in Slovenia would be the famous Postojna Caves. But before we get into the cave system itself, I think it’s worth looking at the area’s geography.

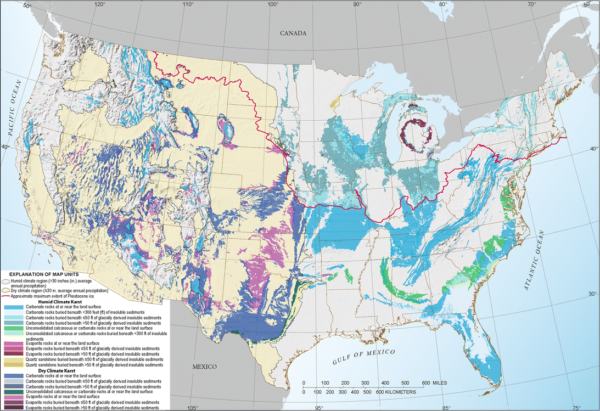

I already mentioned that to reach Postojna we’d be driving across the Karst Plateau. The Karst region covers most of southwestern Slovenia and a portion of northeastern Italy where the edge of the plateau marks the traditional ethnic boundary between ethnic Italians and Slovenes. The formation of the Karst Plateau is unique enough that it gave rise to the geological term karst topography. Thus, it’s sometimes called the Classical Karst. But you can find karst topography all over the world. For example, there’s a very large karst area in the U S that covers part of southern Indiana, central Tennessee, and western Kentucky along with others throughout the country as seen on the map from Springerlink below. And,  you can see some international karsts in photos farther down the page.

you can see some international karsts in photos farther down the page.

What is a karst? A karst develops when acidic water flows through and across porous bedrock composed of limestone, dolomite, or gypsum. This rock, more susceptible to erosion than other types of rock, begins to break down near its cracks or bedding planes. With time, as the process continues, the cracks get wider and eventually a drainage system of some sort may start to form underneath. When that happens, the process of erosion and breakdown generally accelerates.

When the process accelerates, a variety of small-scale to large-scale┬Āfeatures emerges both on the surface and beneath it. Small surface features have some cool monikers like rillenkarren, runnels,┬Āor clints and grikes. Medium-sized surface features will often include sinkholes or closed basins known as┬Ācenotes, vertical shafts,┬Āinverted funnel shafts called foibe (Remember the foibe massacres of Istria? They were so named because bodies were buried in this type of shaft.), disappearing streams, and reappearing springs. Large-scale features may include limestone pavements, poljes, and karst valleys.

In a mature karst landscape, you might see karst towers like this one in Andalusia

or this one in China.

Now that you should have a reasonably clear picture of what the surface of a karst looks like, in the next post we need to look at what’s happening below the surface. (We are going into a cave, after all!)

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kuk├½s

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026

2 responses to “Feeling sLOVEnia – part 1”

What a lovely chapter, Todd. Dragons, Caves and Castles. Splendid. The cave is amazing – and I found myself making a note to see if I could find documentaries on the engineering feat to make the train and general excavation of the cave to allow for visitors. Fascinating.

As was the capital city – great architecture and the dragons are compelling (especially to those of us who read Science Fiction and Fantasy).

Felt Parisian, for some reason, only with more whimsy.

You make it sound more Tolkienesque than it was. I like it!