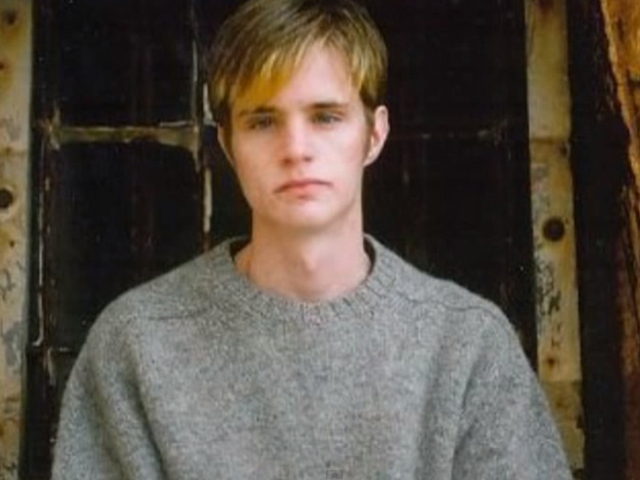

A fuller portrait.

There’s no question that Matthew Shepard was a bright young man. The child of an upper middle-class family, by the time he enrolled in college, he was a straight-A student who spoke three languages. Physically, though, he was small and looked younger and more vulnerable than his age.

Rather than fulfilling an apparently promising future, sometime during his time in Laramie, Shepard’s behavior changed. According to Jimenez, Shepard had been raped during a visit to Morocco several years earlier and was prone to bouts of depression. Jimenez came to no conclusion regarding the significance of this event in changing Shepard but, over time, his grades fell and he began using drugs – principally crystal meth.

Jimenez learned that by the night of his murder by Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson on 6 October 1998, Shepard had been prostituting himself to support his drug habit, he was also selling drugs, and he was HIV positive. Further, Shepard knew both McKinney and Henderson and had occasionally had sex with McKinney who, it appears, had also periodically prostituted himself alongside Shepard. The key difference between them was that Shepard had, in some ways, come to terms with his sexuality while McKinney, as evidenced by both his court testimony and his interviews with Jimenez, had not.

Like Shepard, McKinney was also a meth addict and it wasn’t Jimenez’s account alone that gave some credence to the notion that McKinney had been on a methamphetamine bender for at least five days before the night he and Henderson murdered Shepard. In fact, McKinney assaulted three other men later that night. In an interview after the trial, the prosecutor stated that it was “a murder that was driven by drugs.” It’s possible Matthew Shepard’s murder was a drug crime. It’s also possible it was a hate crime motivated in part by Aaron McKinney’s self-loathing and fueled by a drug induced rage. It’s likely it was a bit of both.

In the end, none of this changes the sheer brutality of Matthew Shepard’s murder nor his vulnerability as a gay man. Neither does it necessarily make him less deserving of his memorial bench on the University of Wyoming campus or being honored by the law that bears his name. Nor does it in any way minimize the loss felt by his family and friends.

But, as Aaron Hicklin wrote in The Advocate,

There are valuable reasons for telling certain stories in a certain way at pivotal times, but that doesn’t mean we have to hold on to them once they’ve outlived their usefulness. In his book, Flagrant Conduct, Dale Carpenter, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, similarly unpacks the notorious case of Lawrence v. Texas, in which the arrest of two men for having sex in their own bedroom became a vehicle for affirming the right of gay couples to have consensual sex in private. Except that the two men were not having sex, and were not even a couple. Yet this non-story, carefully edited and taken all the way to the Supreme Court, changed America.

In different ways, the Shepard story we’ve come to embrace was just as necessary for shaping the history of gay rights as Lawrence v. Texas; it galvanized a generation of LGBT youth and stung lawmakers into action. President Obama, who signed the Hate Crimes Prevention Act, named for Shepard and James Byrd Jr., into law on October 28, 2009, credited Judy Shepard for making him “passionate” about LGBT equality.

There are obvious reasons why advocates of hate crime legislation must want to preserve one particular version of the Matthew Shepard story, but it was always just that — a version. Jimenez’s version is another, more studiously reported account, but he is not the first to challenge the popular mythology. Way back in 1999, Wypijewski rejected what she called the “quasi-religious characterizations of Matthew’s passion, death, and resurrection as patron saint of hate-crime legislation” in favor of what she called “wussitude” — a culture of “compulsory heterosexuality” that teaches young men how to pass as men, unfeeling, benumbed, primed to cloak any vulnerability in violence.

If Shepard’s martyrdom has played a role in creating a more humane world with respect to the gay community, then the full picture of his life shouldn’t diminish that view of him. But, as is the case with most martyrs to any cause, however righteous, we need to see his portrait not in black and white but in full color.

One last and very quick stop.

On my way out of Laramie on the morning of 2 September, I stopped to fill the car with gas and coincidentally spotted one last photo op that Roadside America had mentioned. The site bills it as “The Gas Station Town of Tumbleweed” and describes it this way:

The “Gunslinger 66” (Phillips 66) gas station has been a Laramie tourist stop since at least the 1970s, and probably before that. Inside the mini-mart are animal heads on the walls, displays of Old West artifacts in glass cases, and a good selection of postcards. Out back, behind the diesel pump island, is a full-size fake-front Wild West main street, complete with a boardwalk sidewalk and a livery stable, bank, hotel, general store, and the Dry Skull Saloon.

It seems to have been designed as a very elaborate backdrop for visitor photos. A sign next to pumps identifies it as the town of Tumbleweed, with a dwindling population of 7.

The morning of my visit, this was its appearance:

and turning to the right from this perspective, you can see that the store is closed but the pumps are open. And yes, that’s my shadow on the right.

And now it’s time to set off and see some more of the Cowboy State – or at Wyoming officially calls itself – the Equality State.