When I reported on the segment of the trip from Deadwood to Sundance, I mentioned my stop at the Southeast Wyoming Welcome Center where I’d had the odd coincidence of crossing paths with the family from Maryland for the second time that day. While I was there, I also found information about an interesting place to stop that required only a small detour on my way from Laramie to Fort Washakie on the Wind River Reservation which itself was just a small detour I’d planned to make en route to Jackson. And if you don’t take detours, what’s the point of road trips?

Independence Rock – Gray whale of the prairie

From a distance of 150 yards or so, Independence Rock looks like this

and, of course, if you take in the satellite view from Google Maps, you get a broader perspective.

and, of course, if you take in the satellite view from Google Maps, you get a broader perspective.

Human nature is enough to make a place like Devils Tower an object of wonder because it’s not merely singular within its local geography, there’s nothing comparable to it anywhere in the world. (Some might consider Gilbert Hill in Mumbai as similar but it’s one-fourth the height of Devils Tower and wasn’t always as isolated a formation as it is currently.)

Even if Independence Rock was the lone formation of this type in the area, and the satellite photo above shows that it’s not, neither its composition nor its size makes it unusual. For example, although it’s more than 1,200 miles to the south, the larger rounded granite batholith called Enchanted Rock near Llano, Texas is similar both in composition and appearance.

Also, unlike the Tower or the rocks of the Foothills Erratics Train, Independence Rock itself fits with its surroundings. It’s a large, rounded monolith of Archean granite that’s typical of the surrounding region. It stands out a bit because of it size, and relative isolation at the southeast end of the Granite Mountains. (Nearly 700 feet wide and 1900 feet long, the rock is more than a mile in circumference and peaks 136 feet above the prairie below.) So it’s not particularly special geologically or geographically. To get the first hint of its importance, you need to look at the map reproduced below. Independence Rock is a place of significance with regard to westward migration along the Oregon, California and Mormon Trails.

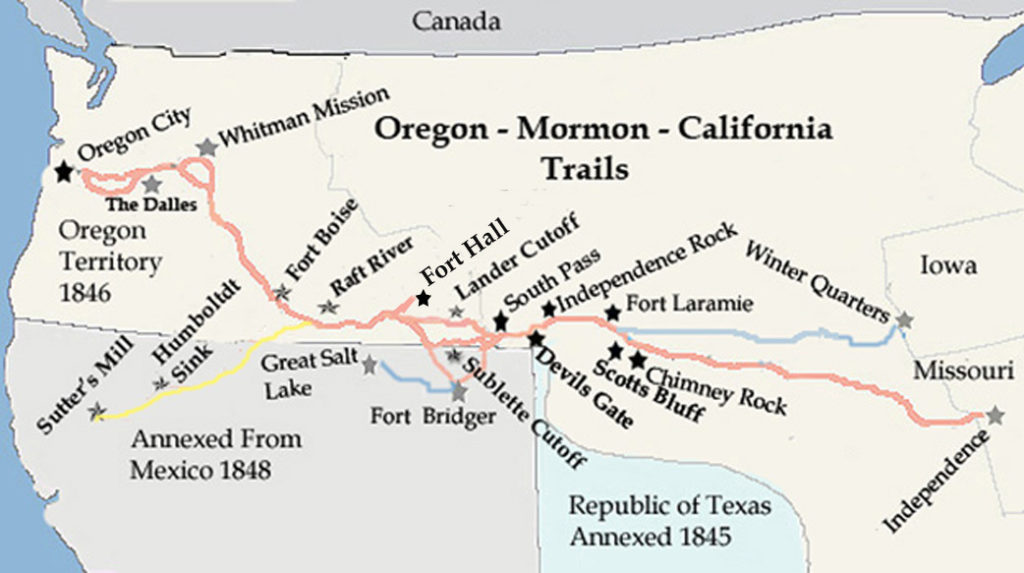

Search the internet for a map of the route of the Oregon Trail and you’re likely to find a map like this:

Perhaps the most important route used by European Americans as they settled the west throughout the 19th century was the Oregon Trail – a route connecting Independence, Missouri at its eastern terminus and ranging as far as Oregon’s Willamette Valley in the west. Recognizing the importance of water, the trail was designed to follow river valleys whenever possible. And, as you can see from the photo above, Independence Rock is adjacent to a river – in this case, the Sweetwater.

You don’t have to look very closely at the map to spot Independence Rock just west of Fort Laramie. (Note the pale blue line that indicates the Mormon Trail – a route I discussed in recounting my trip to Arizona and Utah. The map also shows in yellow the southern cutoff used by prospectors headed for Sutter’s Mill or elsewhere in California.)

The earliest European accounts of the rock date from the 1820’s though the tribes that ranged the central Rocky Mountains – Arapaho, Arikara, Bannock, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, Lakota, Pawnee, Shoshone, and Ute – were all familiar with and left pictographs and petroglyphs on the site they came to call Timpe Nabor or the Painted Rock (though I could find no account that indicated the rock held any special spiritual significance). Perhaps inspired by the Native American markings, westward bound Europeans then painted and carved their names into it.

The best evidence for the source of the formation’s current moniker is that a fellow named William Sublette, while leading a wagon train toward Wind River, christened the rock in 1830, “having kept the 4th of July in due style.” One other legend claims that Thomas “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick named “Rock Independence” when he passed by it on 4 July 1824. Yet another proposed explanation for the name is that emigrant wagon parties bound for the west coast attempted to reach the rock by July 4 to facilitate reaching their destinations before the first mountain snowfalls.

Rising from the surrounding prairie as it did, the formation evoked many colorful descriptions. In 1832, John Ball thought the rock looked “like a big bowl turned upside down,” and estimated that its size was “about equal to two meeting houses of the old New England Style.” Hervey Johnson, a Civil War veteran described it as looking like “a big elephant up to his sides in the mud.” And a Mr. J. Goldsborough Bruff wrote that the rock “looks like a huge gray whale.”

However one sees its appearance, an uncounted number of migrants left their marks either painted or carved into the rock (or in some cases paid someone to leave a mark on their behalf). By the time pioneer priest, Pierre-Jean De Smet, (whose name you remember from the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie) saw the rock in 1841, he found “the hieroglyphics of Indian warriors” and “the names of all the travelers who have passed by are there to be read, written in coarse characters.” He dubbed the rock “the great register of the desert.”

Visitors today can climb the rock

though I chose not to do so. Frankly, it was the descent not the ascent that sparked my caution.

A second Devil in Wyoming

Take another look at the map above and just a tiny bit west of Independence Rock you’ll see a spot marked Devils Gate. In the 19th century, travelers needed nearly a day to journey from Independence Rock to Devils Gate. On the second of September in 2017 I needed all of eight or ten minutes to drive near the site and less than an hour to walk around the Sun Ranch historic site to get quite close to it.

Although it’s considered a major landmark along the three trails (Oregon, California, and Mormon) none of the trails actually passed through the narrow cleft in the granite Sweetwater Rocks carved by the river of the same name. According to Wikipedia,

Devil’s Gate is a remarkable example of superposed or an antecedent drainage stream. The Sweetwater River cuts a narrow 100-meter deep slot through a granite ridge, yet had it flowed less than a kilometer to the south, it could have bypassed the ridge completely. The gorge was cut because the landscape was originally buried by valley fill sediments. The river eroded downward and when it hit granite, it kept on cutting.

One Native American legend describes the formation of the rift as being the work of an evil beast with enormous tusks that once roamed the valley. The beast prevented the Indians from hunting and camping and eventually, the Indians decided to kill it. From the passes and ravines, the warriors shot the beast with a multitude of arrows. However, the enraged beast tore the cleft in the mountains with his large tusks and escaped.

The cleft itself is 370 feet deep and 1,500 feet long. Even more noteworthy, it’s a mere 30 feet wide at the base but nearly 300 feet wide at the top. As they did at Independence Rock, emigrants frequently stopped to hike around these rocks and carve their names while also watching bighorn sheep climbing the hills. “The chasm is one of the wonders of the world,” emigrant Charles E. Boyle wrote in 1849. “The water rushes roaring and raving into the gorge, and the noise it makes as it comes in contact with the huge fragments of rock lying in its course is almost deafening.”