Although I teased you a bit with the final section header in the previous post, it’s now, time to visit the Vore Buffalo Jump. I know I should call it a bison jump but buffalo is the common term so, as I’ve done elsewhere in this blog, I’ll use it particularly when it’s included in a place name as in this instance.

For perhaps as long as 12,000 years, the people of the plains used the method of hunting bison typified at the Vore Buffalo Jump. Although the pit at this particular location has an estimated age of only three centuries, ongoing excavations continue to push that age further back in time.

Life for the nomadic tribes of the North American plains wasn’t easy and because they had little or no formal agriculture, winters could be particularly harsh. Summer and winter hunting were quite different. To survive the long hard winters, tribes would organize one massive hunt, usually in late autumn, to amass what was needed to feed and clothe the tribe until spring. Before the arrival of horses and rifles, the tribes engaged in a buffalo jump.

One trait of bison is that, unlike their domesticated bovine cousins, they cannot be driven. Try to drive buffalo and the animals respond by charging or running in any direction other than the one of the attempted drive. Thus, to succeed in this type of hunt, a less direct approach is needed. At the beginning of the hunt, one or more young men of the tribe would begin a process described as “worrying” the herd. Sometimes disguised under wolf hides, they would worry the herd enough to encourage it to move in the general direction of the jump.

Often, the tribe would have constructed an ever-narrowing series of stone cairns extending as far as one to three miles from the pit. These served as drive lanes through which the bison could then be funneled into a pit or over a cliff. As they neared the pit, other young warriors, covered in buffalo hides would take the exceptionally dangerous role of leading the herd over the edge.

The animals would be slaughtered on site with a use for nearly every part of the bison – using the hooves to make glue, tanning hides with the animal’s brains, and making pemmican. (Pemmican is a concentrated mix of fat and protein. Etymologically, it’s derived from the Cree word pimîhkân. Pemmican traditionally used lean meat cut into thin slices and dried over a slow fire until it turned brittle. The dried meat was pounded almost to a powder then mixed with melted fat. At this point, ground dried fruit such as cranberries or choke cherries were added. Packed into a rawhide storage bag, the completed product could remain edible and nutritious for as long as a decade.)

A serendipitous discovery.

Sinkholes are fairly common and often ignored in eastern Wyoming and this particular sinkhole had filled with sediment over time so when the Vore family established a homestead ranch on the site in the 1880’s they simply went about their business of farming and grazing cattle and thought nothing of it for nearly a century.

Then, in 1970, the government began its surveys for the proposed route of Interstate 90 and part of that route, the part that would cross the southern portion of the Vore’s property ran the east bound lane over the north rim of that large sinkhole. While it was conceivable that the sinkhole could be filled with compacted dirt, engineers were concerned because sinkholes are notoriously unstable and they naturally wanted to avoid a possible road collapse.

The Wyoming Department of Transportation, trying to test the site’s stability, used a small rig to drill several holes in the bottom of the sinkhole. Much to their surprise, the drill brought up quantities of buffalo bone. At that point they decided to move the route of the interstate south of the sinkhole. They then notified archaeologists at the University of Wyoming that they had discovered a cultural site of unknown size and importance.

The initial cautious excavations made in 1971 and 1972 showed that the Vore Site is, in fact, quite large. Buffalo bones, tools, and other cultural artifacts extend across the sinkhole in a diameter of nearly 200 feet while the earliest digs found bones to a depth of 23 feet. This allowed the scientists to age the initial discovery to the 17th century.

There were no further excavations for nearly two decades until the family of Woodrow and Doris Vore agreed to donate 8.25 acres that included the sinkhole to the University of Wyoming with the stipulation that it be developed as a research and education center within 12 years. Lack of funds prevented the university from meeting that deadline and the property transferred to the Vore Buffalo Jump Foundation in 2001.

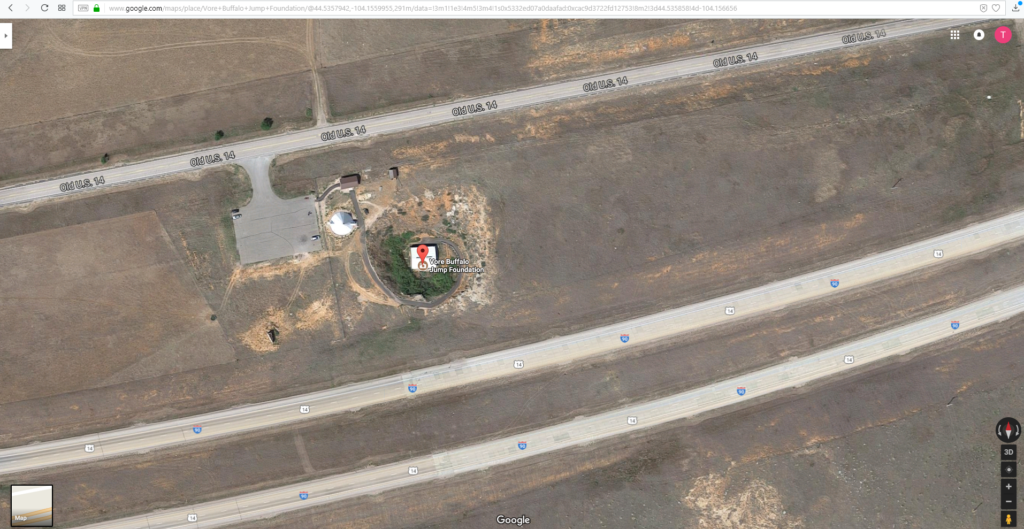

All the work visible in the photo above, from the paved parking lot to the tipi shaped exhibit building to the shelter over the excavation site has been managed with the foundation’s private funds and has been completed in the last decade.

I’m not certain this captures the depth of the hole but I hope it provides some sense of it.

You can see additional photos here.

And finally, Harry Longabaugh.

I think what happened as I left the Vore Buffalo Jump qualifies as ironic. When I travel now, I use a small device that attaches to the air conditioning vent in the car and holds my phone. Since I had no real need for my phone while I was at the buffalo jump, I’d left it in the car. Now, I’ve written at some length about the absence of a data connection that has limited my use of the phone’s navigation apps. You should also recall that I’m still reporting about the same day I misread my hastily handwritten directions and missed the turn to the Needles.

If you look again at the satellite view above, you’ll see that the parking lot exit is onto Old U S Route 14. To reach Sundance, where I’d planned to spend the night, I needed only to turn left out of the parking lot and drive straight for 15 miles into the center of town. Now comes the moment of irony.

I got in the car and started the engine. This then woke up my phone which I kept connected to the car’s USB port to help extend the battery life. Because I have an Android phone, it’s synced to my gmail accounts and when the surge from the USB roused it from its slumber, it began merrily chirping away signifying that I had email messages waiting. This, of course, also signaled that I had a data connection meaning that now that I was a single turn and 15 miles from my destination, I finally had access to the GPS applications. Is this ironic? You decide.

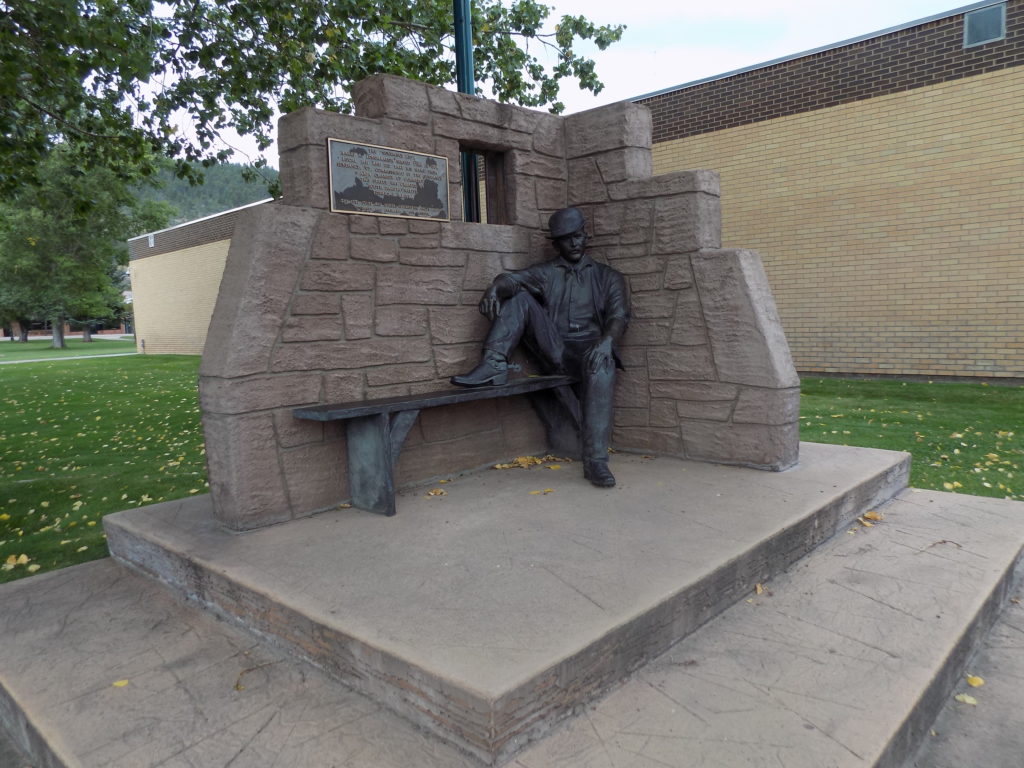

I’d chosen to stay in Sundance because it seemed like a reasonable end point for today’s adventure and a reasonable starting point for tomorrow’s. Even had I not planned to spend the night, I would have driven into the town where one Harry Longabaugh served time in the local jail eventually taking from it the name for which he would become notorious when he rose to fame as the Sundance Kid. And the town is proud of that.

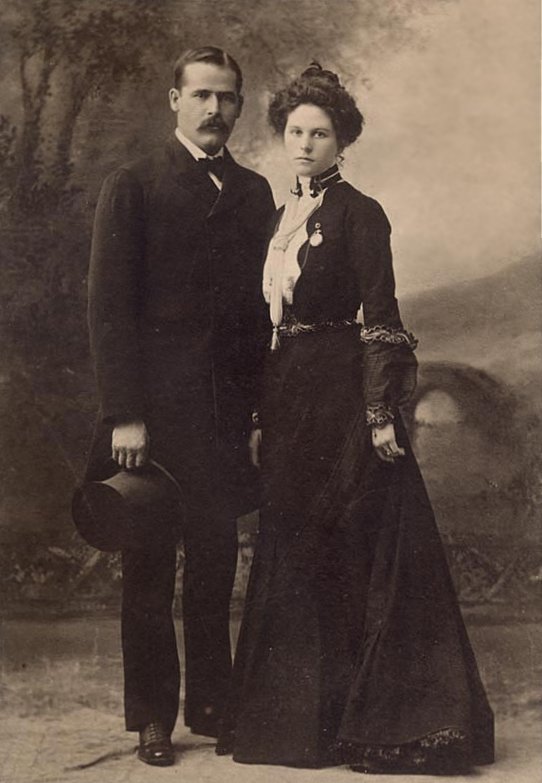

Connected to the “Wild Bunch” gang led by Butch Cassidy, Longabaugh doubtless abetted Cassidy in committing more than a few crimes late in the 19th century. However, the pair were not the close friends as portrayed by Paul Newman and Robert Redford in George Roy Hill’s 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid but Cassidy and Sundance were linked in the public’s imagination when the pair was said to have fled, together with Longabaugh’s wife Ethel “Etta” Place, to South America in 1901. (Cassidy’s best friend in the gang was most likely William Lay, aka Elzy who didn’t appear in the movie.) The truth could be a bit different but I’ll have more to write about that when I visit Laramie.

I’ll have to add my opinion that the real Sundance and Etta [Public Domain photo from Wikipedia.]

were every bit as attractive as their cinematic counterparts (from TCM).

As for the town itself, it’s small with a population around 1,200. I took a handful of photos before having dinner and retiring for the night. Tomorrow, I’ll head south toward Cheyenne and a bit west to Laramie and I promise some surprises along the way.