And so it begins – assassination and aftermath

Immediately after the assassination, the Sarajevo police had both Čabrinović and Princip (who also failed in his attempt to commit suicide) in custody. By the following day, 29 June 1914, their interrogation revealed the names of the five co-conspirators. Seeing the complicity of Serbian subjects, Austro-Hungarian and German diplomats began making requests to their Serbian counterparts as early as 30 June demanding a thorough investigation. Further interrogations of the plotters pointed to a major in the Serbian Army who was also believed to have been a member of Black Hand as the person responsible for giving the assassins their orders. In both cases, the Serbians refused to launch any internal investigation. This triggered what is known as “The July Crisis.”

The Austrians wanted to immediately launch a war against the Serbians but the positions of both the Germans and Russians complicated the situation. The Austrians needed to know which side the Germans would support because the Russians, for reasons of their own, were working toward forming an alliance with Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro against Austro-Hungary. To determine the German position, Emperor Franz Joseph wrote to Kaiser Wilhelm II (pictured below).

(Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain)

The letter closed with him advocating the end of Serbia as a political power factor – a position Wilhelm soon indicated he would support.

The next step toward a declaration of war was finding a mechanism to provide a reasonable and juridical basis for such a declaration. To that end, a council of ministers met in Austria and agreed to present Serbia with a list of demands they would almost certainly reject. Soon the German Ambassador to Austro-Hungary, and the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister were holding almost daily meetings about how to co-ordinate the diplomatic action to justify a war against Serbia.

Some in Austria worried that an Austro-Serbian conflict would likely trigger a world war because they believed any attack on Serbia was bound to lead to intervention by Russia, which saw itself as protectors for the Slavs. Even though Russia was not among the strong military powers in Europe at the time, the Russians had a history of using their almost unlimited manpower to wear down opposing forces. The Austrians repeatedly told the Russians that they had no plans to attack Serbia that summer. On the other hand, the Austrians also feared that the Germans would view not proceeding with their plans as a sign of weakness. The ultimatum was delivered on 23 July 1914 and expired just two days later.

The Serbians turned to the relatively weak European powers of France and Russia neither of which agreed to support them. Faced with this lack of support, Serbia accepted all of the terms of the ultimatum except one. Winston Churchill wrote of the ultimatum, “Europe is trembling on the verge of a general war. The Austrian ultimatum to Serbia being the most insolent document of its kind ever devised.” Still, he believed the British should remain neutral should war break out.

Predictably, the situation quickly spiraled out of control. On 28 July 1914, Austria declared war on Serbia. On 1 August Germany declared war on Russia and then on France two days later – a war they began by invading Belgium. Despite Churchill’s belief that Britain should remain neutral, Britain declared war on Germany on August fourth.

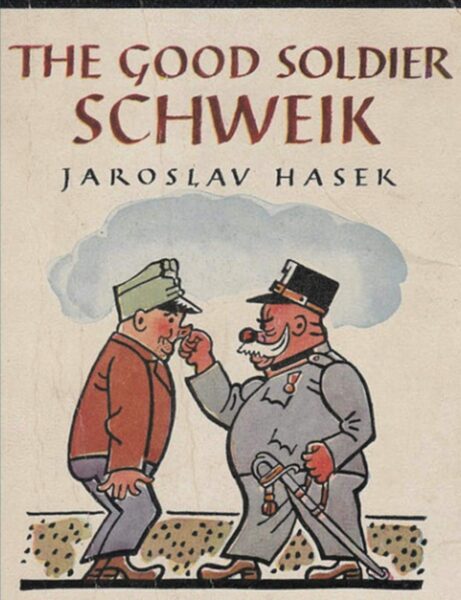

Before returning to what I did in Sarajevo on 12 August 2016, please understand that I have barely scratched the surface of the machinations, feuds, political maneuvering, and squabbles that led to World War One. Princip’s successful assassination of Franz Ferdinand was merely the trigger that provided the excuse to launch a war that had, in all probability, been brewing for decades. But the assassination was the trigger and I stood at or walked very near the spot where it happened. This allowed history to extend its long, long arm and tap not only my shoulder but the shoulder of a young writer in Prague who might have been in a bar drinking at the time. Although he would never finish his planned six volume novel The Good Soldier Švejk,

he would create, in the three volumes he finished, the most widely translated novel in all of Czech literature. (Someone now owes me a beer.)

Let there be bureks!

It’s time to pick up a few threads from my first entry about our time in Sarajevo. In that post I mentioned that, after the first Jewish synagogue burned, Gazi Husrev-Beg endowed the second Jewish synagogue from his personal funds. The fact that a Muslim Bey would make such a gesture might have surprised you particularly in light of the generally belligerent relationship between many Jews and Muslims today. The Bey’s gesture might have become clearer when I later wrote that Muslims and Jews constituted the majority of Sarajevo’s population, that there was no ghetto and, in fact, that Jews and Muslims lived as neighbors while trading openly and equally in the baščaršija.

In fact, the old synagogue, now a museum,

was among the last stops on our group’s walking tour of the city. Jews had a very interesting history in B&H in general and in Sarajevo in particular. While many history books will say that the first Jews arrived in B&H after the expulsion from Spain in 1492, there is some local evidence that at least a small Jewish community predated this mass migration. Still, the Bosnian Jewish population was almost exclusively Sephardic until the Austrians conquered Hungary in 1686 and the first Ashkenazi Jews arrived in B&H and, like their Sephardic counterparts, began living, working, and prospering side by side with their Muslim neighbors.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire gained full control of B&H in 1878 and with them came European capital, companies, and business methods. Many professional, educated Ashkenazi Jews also arrived with the Austro-Hungarians. The Sephardi Jews continued to engage in their traditional areas, mainly foreign trade and crafts.

(It’s time for another digression. This one is for those who don’t know the differences between Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews: Generally, three elements distinguish Ashkenazi from Sephardi. These are religious practice, culture {including language} and ethnicity.

With regard to religious practice, in addition to following Halakha or religious law, most observant Jews also follow minhagim or ancestral traditions. Some examples where the groups’ traditions differ are in the observance of Passover when Ashkenazi Jews traditionally refrain from eating legumes, grain, millet, and rice and Sephardi Jews typically do not prohibit these foods. Sephardim generally have stricter requirements concerning what makes meat kosher. Thus, meat products that might be acceptable to Ashkenazim might not considered kosher by Sephardim.

Culturally, an Ashkenazi Jew can be identified by the concept of Yiddishkeit, which is the Yiddish word for “Jewishness.” In this case Jewishness means an emphasis on religious study by men and a family and communal life governed by the observance of Jewish Law as interpreted by the Ashkenazi for men and women. Some will say that this Jewishness can also be identified in manners of speech, in styles of humor, and in patterns of association. While not true today, most Ashkenazi spoke Yiddish as a first language while the Sephardi generally spoke Ladino in addition to the local language. Another specific cultural difference between the two groups pertains to naming babies. Ashkenazi Jews frequently name newborn children after deceased family members {typically using only the first initial}, but not after living relatives. By contrast, Sephardi Jews often name their children after the children’s grandparents, even if those grandparents are still living.

From an ethnic standpoint, most Sephardic Jews have Mediterranean ancestry while Ashkenazi Jews trace their ancestry to the Jews who settled in Central Europe. A Wikipedia entry about Ashkenazic Jews has this note:

A 2006 study found Ashkenazi Jews to be a clear, homogeneous genetic subgroup. Strikingly, regardless of the place of origin, Ashkenazi Jews can be grouped in the same genetic cohort – that is, regardless of whether an Ashkenazi Jew’s ancestors came from Poland, Russia, Hungary, Lithuania, or any other place with a historical Jewish population, they belong to the same ethnic group. The research demonstrates the endogamy of the Jewish population in Europe and lends further credence to the idea of Ashkenazi Jews as an ethnic group.

{I point this out because my recent DNA test on Ancestry.com showed me to be 100% Ashkenazi.})

To be continued.