On 28 June 1914, near the Latin Bridge in Sarajevo, Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie were shot by Gavrilo Princip – a political assassination that triggered World War I. History often portrays it as that simple. It’s not. History is rarely simple – something that’s especially true in the Balkans.

In the picture of the Latin Bridge posted in the first Sarajevo entry, I was standing on the corner of Zelenih beretki and Obala Kulina bana streets. I was probably close to being directly opposite the spot where the assassination occurred. The archduke wasn’t on the bridge itself and neither was Princip. More on that later. Meanwhile, here’s a different perspective:.

I took the first photo just to the left of the woman in white and the assassination happened just opposite the museum. City Hall is two or three blocks to the right and the Hotel Europe is one block ahead then one block to the left.

The Main Players.

Serbia Black Hand.

Black Hand was a conspiracy group founded and led by Dragutin Dimitrijević who entered the Serbian Army at age 16 immediately following his graduation from the Belgrade Military Academy. Upon establishing Black Hand in 1901, Dimitrijević adopted the name Apis. The group planned and carried out the assassination of King Alexander 1 of Serbia and his wife Queen Draga. Most reports say the scene of the murder was quite gruesome. There are conflicting reports whether Apis was present or not. There’s little question, however, that he planned the act.

The Serbian Parliament, which had seen its constitutional rights suspended by Alexander just days before his assassination, hailed Dimitrijević as a savior of the fatherland. This played well with Dimitrijević who had a borderline obsession with seeing the liberation of all the south Slavs – especially Serbs – from Austro-Hungarian rule and the creation of an independent Serbian state. In his military life, after creating several battle plans that helped the Serbs win a number of skirmishes against the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913, Dimitrijević grew in stature and power ultimately reaching the rank of colonel. In his life as Apis, he and his men, disguised as Albanians, helped Black Hand carry out political executions across Europe. Here’s a photo of Dimitrijević from Wikipedia (Public Domain as are all the historical photos herein):.

Dimitrijević had latched on to an idea that had first appeared in 1844 – uniting all territories where Serbs lived into a “Greater Serbia.” It’s possible that the formal 1908 annexation of B&H by Austro-Hungary to which the Turks eventually acceded, intensified Serbian nationalism. The notion of pan-Serbianism had appeared early in the 19th century but the idea of territorial expansion didn’t take hold until the middle of the century. (The notion of a “Greater Serbia” also wove its way into the rhetoric of Slobodan Milošević more than a century later.)

In 1911, fearing that Emperor Franz Joseph’s plans to grant concessions to the South Slavs would complicate his desire to establish a unified Serbian country, Apis plotted the emperor’s assassination. Those plans went nowhere.

Eventually, news that the emperor’s nephew Franz Ferdinand had accepted an invitation to visit Sarajevo and review troops there reached Apis now Chief of Serbian Military Intelligence in Belgrade. He sent seven men from Bosnia to assassinate the presumptive heir to the throne. The eventual killer, Gavrilo Princip, was one of three Bosnian Serbs among the seven.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Presumptive Heir.

Franz Ferdinand was born in Graz, Austria in 1863 and was the nephew of Emperor Franz Joseph. When Franz Ferdinand was 26, his cousin Crown Prince Rudolph, committed suicide leaving his father Karl Ludwig as first in line to the throne. In 1896, Karl Ludwig died of typhoid fever and Franz Ferdinand moved one step closer to becoming emperor.

Historians paint conflicting pictures of Franz Ferdinand’s politics. On one hand he’s known to have advocated granting greater autonomy to ethnic groups within the Empire and addressing their grievances, especially the Czechs in Bohemia and the south Slavic people in Croatia and Bosnia. On the other, he exhibited a clear measure of dynastic centralism, Catholic conservatism, and tended to speak bluntly and clash with other leaders.

Franz Ferdinand broke from tradition when he married for love. He met his future wife Countess Sophie Chotek at a ball in Prague in 1894. Unfortunately, the Choteks were not one of the reigning or formerly reigning dynasties of Europe which was a prerequisite to marry into the Imperial House of Habsburg. The two carried on a secret relationship for years and Franz Ferdinand fell so deeply in love with Sophie that he refused to consider marrying anyone else.

Franz Joseph finally relented and in 1899 permitted their marriage but with many conditions. First, that their descendants wouldn’t have succession rights to the throne. Additionally, Sophie was barred from sharing her husband’s rank, title, precedence, or privileges. As such, she wouldn’t normally appear in public beside him. Typically, when the couple assembled with the other members of the imperial family, Sophie was forced to stand far down the line, separated from her husband.

They were married on 1 July 1900 and had three children – a girl, Sophie, and two boys Maximillian and Ernst. The public appearance ban held until a trip to Sarajevo in June 1914.

If at first – The Assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

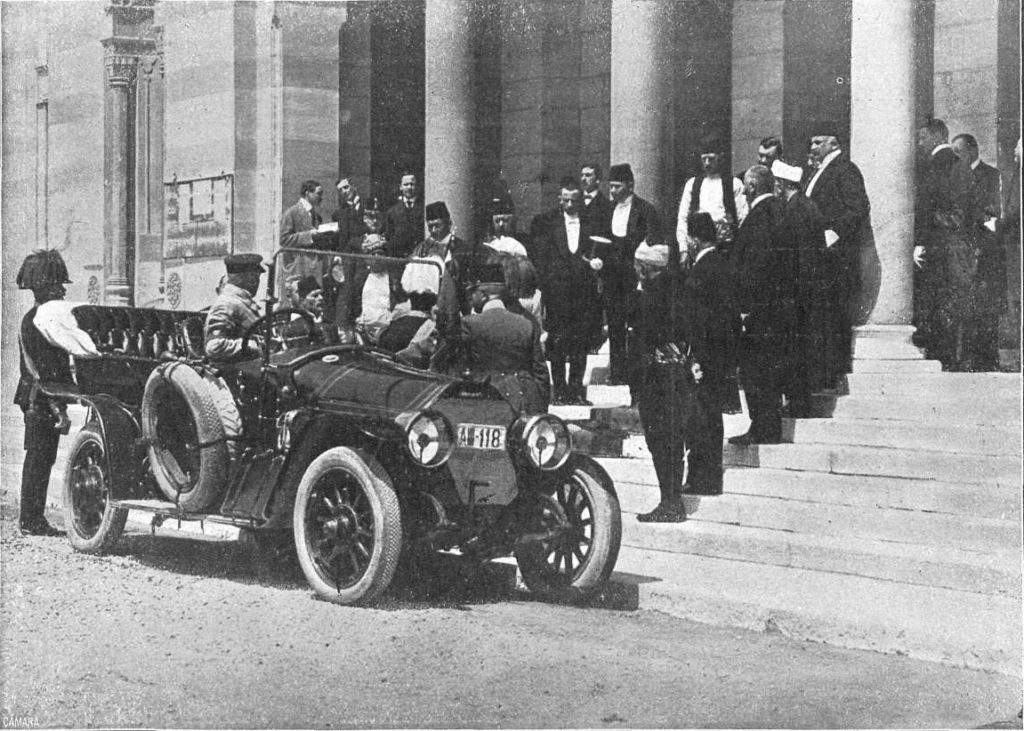

Before their planned arrival in Sarajevo, Franz Ferdinand and Sophie had stopped at the thermal spa in Ilidža. (If you’re thinking you’ve heard about this spot, you have. I mentioned it in connection with the Romans and their use of it during their rule. It’s near the airport about 11 kilometers from the city center.) They arrived in Sarajevo by train where the governor and a six-car motorcade met them. Then the mistakes began.

First, although an officer in the Serbian Army had informed the Serbian prime minister of the assassination plot, the security arrangements were rather thin. The local military commander fearing that lining the route with military troops would offend the locals, ordered that protection of the visitors be left to the local police only 60 of whom were on duty that day. Additionally, three of the local police officers got into the first car with the chief officer of special security leaving behind the special security officers who should have accompanied their chief.

The seven assassins were stationed near various bridges along the route. The first two, perhaps losing their nerve, took no action. The third, Nedeljko Čabrinović, was on the opposite side of the river carrying a hand grenade armed with a timer. He missed his target but the bomb exploded near one of the trailing cars in the motorcade injuring about a dozen people – most of whom were simply bystanders.

The already dense crowd thickened as people tried to flee the scene and the motorcade sped up leaving the remaining conspirators unable to attack it. Following orders, Čabrinović swallowed a cyanide capsule and jumped into the Miljacka River but his suicide attempt failed and the police soon took him into custody. The motorcade completed its rush to City Hall

where the mayor greeted the Archduke who was less than diplomatic in his response. Sophie calmed her husband and the program soon got back on track. After addressing the assembly at City Hall, Franz Ferdinand was scheduled to meet with town leaders at the Hotel Europe (coincidentally, where our group was staying). However, the royal couple changed their plans deciding to visit those wounded from the bombing.

where the mayor greeted the Archduke who was less than diplomatic in his response. Sophie calmed her husband and the program soon got back on track. After addressing the assembly at City Hall, Franz Ferdinand was scheduled to meet with town leaders at the Hotel Europe (coincidentally, where our group was staying). However, the royal couple changed their plans deciding to visit those wounded from the bombing.

With the change in plans, the general in charge of security decided the couple should travel directly along the Obala Kulina bana or Apple Quay as it was then known. Unfortunately, one of the general’s aides had been injured in the bombing and the chief of police, who was tasked with notifying the drivers, neglected to do so. The lead driver, following the original plan then turned onto Franz Joseph Street. The police chief, riding in the following car with the royal couple shouted for him to stop. The car in front stalled trying to back up and Franz Ferdinand now presented a stationary target.

It’s possible you’ve heard the story that, after the first failed assassination attempts, Princip had stopped in Schiller’s Café (now the museum in the top photo) for coffee or a sandwich. The likelihood that this isn’t true is well documented in this Smithsonian Magazine article written in 2011. It’s more plausible that Princip chose the location strategically thinking it might be an opportune spot on the return route where he would have a second chance to carry out his plan. Seeing the stalled car, Princip stepped forward coming to within about one-and-a-half meters and fired. One bullet found its target hitting Franz Ferdinand in the jugular. The other missed Princip’s supposed second target, the governor, and hit Sophie in the abdomen.