Not the mountains, not the prairies.

In supplement one for Salt Lake City, I introduced the term physiography and it’s going to be useful again as I write about Calgary and the nearby area. Technically, you can find three of Canada’s seven physiographic regions in Alberta but the Canadian Shield section is only a small sliver of the province’s northeast corner. Most of Alberta is in the Interior Plains with the Cordillera nudging its way in from the west.

[Physiographic map from The Canadian Encyclopedia.]

Calgary, in the foothills of the front range of the Rocky Mountains, approximately straddles the two. Elsewhere in this blog, I’ve written in some detail (some readers might call it excruciating detail) about the process of building the Rocky Mountains (Laramide Orogeny), the types of mountains and rocks you will find throughout the chain, and some of the other processes (such as the waxing and waning of the Western Interior Seaway) that created the current topography. So I’ll take a slightly narrower view of Calgary and its surrounds.

Not a pelvic thrust but still a bit in-say-yay-yay-n.

Hop on the Trans-Canada Highway driving west from Calgary toward Canmore (home of the cross country skiing and biathlon events in 1988) and in about 45 minutes you get the first real sense that you’ve arrived in the Canadian Rockies when the wall of Mount Yamnuska pierces the sky in front of you.

[Photo of Mount Yamnuska from Wikimedia Commons BY Chuck Szmurlo CC 3.0.]

I chose this mountain as one point of focus not because of its proximity to Calgary relative to other mountains in the chain but because of several characteristics that make it particularly interesting – not the least of which is its name but more on that later.

Walk around Calgary and the land you’re walking on is likely part of the Belly River Formation which is a stratigraphic layer comprised primarily of sandstone in the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin. As I noted in the post linked above, the Western Interior Seaway once covered much of this area and it laid sandstone deposits along coastal and near shore environments in the late Cretaceous about 75 million years ago.

One of the interesting characteristics of Mount Yamnuska is that the Belly River sandstone is at the bottom of the mountain. Moving up the mountain we find massive limestones, with dolomite mottling. These are from the middle Cambrian Eldon Formation making these particular rocks on the order of 500 million years old.

In the normal course of examining rock strata one would expect to find the oldest rocks at the bottom layer that get progressively younger as one moves closer to the surface or farther above it.┬Ā So, it would be reasonable to ask how did the 500 million year old rocks get above the 75 million year old Belly River sandstone.

The answer is the McConnell Thrust Fault. A thrust fault is a place on the Earth’s surface where older rocks are pushed above younger ones. It happens something like this:.

[Depiction of thrust fault from cgenarchive.]

The mountain’s dramatic shape results from differential weathering of the two rock units that make up the mountain – Cambrian limestone and Cretaceous sandstone.

An interesting name change.

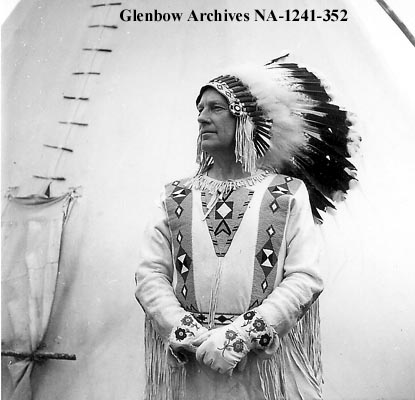

Now, about the name. The name I’ve used thus far, Yamnuska, is derived from the Nakoda (also known as Stoney) word Iyamnathka┬Āthat means wall of stone. However, in 1961, the name was officially changed to Mount John Laurie (sometimes just Mount Laurie). My interest in the name designation piqued when I learned that the change had been made at the request of the Nakoda people. Here’s a little about Mister Laurie (who also has an eponymous street in Calgary).

Laurie was born on a farm in Blenheim Township, Oxford County, Ontario. He moved west after serving in the Canadian Armed Forces during World War I where he taught at Western Canada College in Calgary for several years before moving in 1927 to Crescent Heights High School where he spent the remainder of his teaching career as a drama and English teacher (which certainly makes me feel some affinity toward him).

By 1939, he allowed his concern about various native causes to turn him into a political activist who aggressively supported the drive for native rights. He also advocated for native education not only by housing some indigenous boys himself so they could attend Crescent Heights, but also finding housing that would accommodate tribal girls.

In 1940, Nakoda Chief Enos Hunter and his wife adopted Laurie and named him White Cloud.

[Photo of John Laurie as White Cloud from Calgaryguardian.]

Four years later he became Secretary of the Indian Association of Alberta – a post he held until 1956 when he became too ill to maintain it.

When the Canadian government proposed the New Indian Act, a law that granted First Peoples the right to vote, Laurie fought against it as aggressively as he had fought for other tribal rights in the past. The original proposal granted natives the vote but erased their native status which would have effectively denied their land rights. He wrote of the proposed law in 1950, “It’s only equal is the miscegenation laws of the deepest south.” You can read more about John Lee Laurie here to discover even more reasons why the Nakoda hold him in such high esteem that they chose his name over the native one for the wall of stone mountain.

Know the nose.

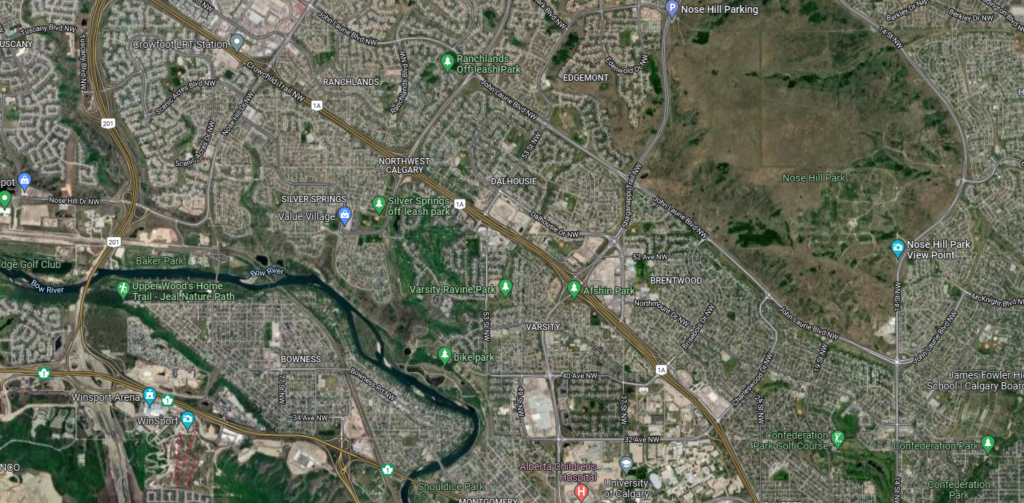

Before I move on to the earliest human settlements in the Calgary area, I’m going to make a brief stop at Nose Hill Park – the fourth largest urban park in Canada. For the moment, let’s jump into the WABAC machine and let it carry us back about 60 million years to watch the birth of the Canadian Rockies. As we look down at the site where we will land in Calgary when we return to the present, we see a broad river perhaps 10 or 12 kilometers wide flowing down out of the mountains. It might be following a path similar to today’s Bow River as seen in the image below taken from Google maps.

However, the ancient river and riverbed would cover nearly everything we see as dry land today. (And if you enlarge the map, you should be able to spot John Laurie Boulevard.)

Rivers being what they are, this one would have been slowly eroding the mountains and leaving fluvial sediments along its course. These deposits are the earliest beginnings of Nose Hill.┬Ā As we rush toward the present, many periods of glacial advance and retreat will similarly rush past our view so quickly that we’re unable to notice the gradual deposition of glacial till to the top of the hills as the glaciers carve the valley. We slow to a stop about 20,000 years ago to look at the retreating glaciers of the Last Glacial Maximum.

Now we see ice from the Rockies cutting into the valley, eroding the fluvial gravel, and dropping boulders called erratics as the ice recedes and melts. (There’s an erratic boulder on Nose Hill and I visited the largest of them in the province called simply the Big Rock in Okotoks on my 2017 trip.)

Before I close today’s post, I’ll add this tidbit from Wikipedia about Nose Hill’s name,

The origin of the hill’s name is unclear but common legend tells of a European explorer asking an aboriginal translator the name of the hill seen far off in the distance. The man replied: Nose Hill is the name it was given because from here it resembles the nose of our chief.