I decided to write today’s post in red because it’s about my walk to and past the Ungarisches Haus (Hungarian House) at 12 Augustinerstraße – the Vienna home of Countess Elizabeth Báthory. Elizabeth was born to a noble family in Nyírbátor in the northeast corner of Hungary and while we will never know to what degree the details of her story are true, they are the stuff of legend. A very evil legend.

The birth and early life of Elizabeth.

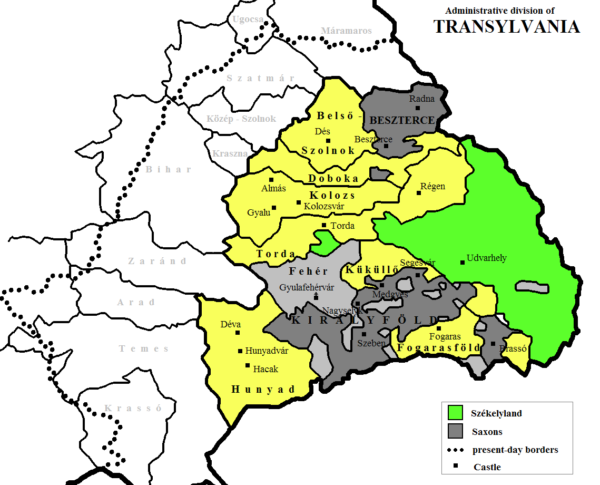

Elizabeth Báthory was born on 7 August 1560 and was the daughter of Baron George VI Báthory of the Ecsed branch of the Báthory family and the niece of Andrew Bonaventura Báthory, who had been voivode of Transylvania – the highest-ranking official in Transylvania within the Kingdom of Hungary from the 12th century to the 16th century. (The native form of her name would be Ecsedi Báyjori Erzsébet but, as always, I will use Western name order.)

[Map of Transylvania from Wikipedia – No attribution CC BY SA 3.0].

As a child, Elizabeth reportedly suffered from “falling sickness” – the term typically used to describe epileptic seizures. Having this condition would be unsurprising since her parents were closely related before their marriage. One of the treatments of the time according to an article published in The Journal of Epilepsy in 1995, included rubbing blood of a non-sufferer on the lips of an epileptic or giving them a mix of a non-sufferer’s blood and piece of skull as their episode ended. It’s impossible to say how much her condition or this type of treatment, if it was administered, contributed to her behavior later in life.

Although she was privileged with wealth, a high social position, and an excellent education she was nevertheless, a girl, and therefore a pawn to be used to form a political alliance. Elizabeth was betrothed at age 12 to Count Ferenc Nádasdy five years her senior. They were married on 8 May 1575 – three months before Elizabeth turned fifteen. Nádasdy gave Elizabeth his household including the Castle of Csejte where she would eventually die at age 43 but I’m getting ahead of myself.

[Portrait of Ferenc and Elizabeth Nádasdy from Wikimedia Commons Csejte Museum By János Korom Dr. >).

What’s a countess to do?

As a youthful bride Elizabeth found herself married to a man of some military ambition and, with the Ottoman Empire occupying much of the Christian southern-central part of Hungary, he had ample opportunity to prove his worth. Early in his career he helped the Hungarians oust the Ottomans from the castles at Esztergom, Waitzen, Visegrád, and Székesfehérvár. In doing so he frequently left Elizabeth alone requiring her to manage the estates. Fortunately for Ferenc, her education and upbringing put her in position to do so effectively.

His frequent absences, however, meant that Elizabeth didn’t give birth to the first of their five children until they had been married for ten years. It’s likely that, given the role of women at the time, this resulted in some people viewing Elizabeth with a degree of unwarranted suspicion particularly since her management seems to have been effective in expanding her family’s wealth and power. Her Calvinist faith in a Lutheran dominated country also made people view her warily.

It was in the last decade of the 16th century that rumors began to surface about some nefarious happenings at Csejte Castle. People began whispering that Elizabeth was torturing her servants. When Ferenc died of an unknown illness on the battlefield in 1604, not only did the rumors proliferate but the violence they described intensified even to the point of murder.

The birth and death of the Blood Countess?

At first, her targets were said to have been poor girls and young women whom she enticed to the castle with promises of servant work with others possibly being abducted. There were certainly credible reports at the time of the disappearance of peasant girls in the vicinity of the castle.

To this point the court and nobility remained unconcerned because they had little interest in peasants who disappeared. However, in the early 17th century, it was said she began killing daughters of the gentry who were sent to her for their education.

[Portrait of Elizabeth Báthory from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Servant girls were one thing. Noble girls were something else altogether. So, in 1610, after Báthory had allegedly killed multiple girls of noble birth, King Matthias II of Hungary sent György Thurzó, the Palatine of Hungary, to investigate.

The reports Thurzó amassed from more than 300 “witnesses” were a compilation of horrifying acts of depravity ranging from covering her victims in honey and allowing bugs to eat them alive to biting off chunks of their skin herself. Others stated that she regularly used scissors to mutilate her victims.

The most infamous accusation against her asserted that she bathed in the blood of her victims believing it would maintain her youthful appearance. This is the claim that gave rise to calling her the Blood Countess. I must stress, however, that this claim doesn’t appear in any of the contemporary testimony even from Thurzó’s witnesses who may have been coerced to provide their evidence. The claim first appeared in print in 1729 – more than a century after Báthory’s death – in a work by Jesuit scholar László Turóczi.

Thurzó ultimately charged her with the deaths of 80 girls. One witness claimed to have seen a book kept by Báthory herself, where she recorded the names of her victims – 650 in total. This is the “evidence” that landed Báthory in the Guinness Book of World Records as the most prolific female murderer in the western world. The diary appears to be more myth than fact.

Báthory and her four servant accomplices were put on trial. All were convicted though Báthory wasn’t permitted to testify in her own defense. The servants were burned at the stake but Elizabeth was effectively placed under house arrest and confined to Csejte Castle where she died in her sleep four years later.

Meanwhile in Vienna.

At the beginning of this post I noted that the residence at 12 Augustinerstraße was called Ungarisches Haus. It was part of Ferenc Nádasdy’s estates. Some say that Elizabeth’s sadistic tendencies first manifested themselves when she stayed there while in Vienna. Certainly, the city’s nearby markets would have been an ideal location for her servants to find and lure girls to the Báthory residence. According to thelocal.at, “Legends tell that the monks in the Augustinian monastery across the street hurled pots at the house, trying to get the screaming from servant girls to stop.” Today, 12 Augustinerstraße is a private residence from which no screams emanate

and which can only be viewed from the outside. But it’s still a fascinating and hidden line written in Vienna’s long history.

Mitigating Evidence.

The aristocratic Elizabeth Báthory was certainly a sadist and almost equally certainly a murderer or, at a minimum, an accomplice to murder. She probably believed her wealth and status protected her. In fact, in some ways, it did. She was unprosecuted for a decade or more – and likely would have remained so had her crimes not extended to other nobility – and, unlike her accomplices who were executed, she was able to die at her home in her sleep. But there could have been other forces at work in her prosecution.

First, as noted above, she was a Calvinist among Lutherans and Catholics. Second, her competence in managing her estates after her husband’s death and continually increasing the wealth and power of her family almost certainly made King Matthias view her as a potential threat.

There’s also some evidence that King Matthias II owed Báthory’s late husband, and by extension Elizabeth, a sizable debt that he was disinclined to pay. Some historians now posit that this, rather than her crimes themselves, provided Matthias sufficient motivation to incriminate her and it certainly seems that Thurzó was intent on incriminating her.

Although it wasn’t imposed, the mere fact that the king called for the death penalty and completing the trial before her family could intervene allowed him to take possession of her land including the Castle at Csejte.

[Photo of Castle at Csejte from Revisiting History].

Is it possible then that the story of the Blood Countess is one of a cruel sadist – perhaps a murderer – who had the misfortune of being an intelligent, powerful woman who owned strategically important land and managed it effectively but who ran afoul of local religious authorities and an indebted intimidated king both of whom used her sadistic behavior to dispose of a perceived threat?

It’s a question likely to remain forever unanswered but one that shows how a little digging can always unearth more to the story.

And there’s still more to the story of my first full day in Vienna but that will have to wait until my next post where you’ll also find a link to all the pictures from the afternoon.

HBaTM

80 proven kills would put her 4th all time on the serial killer list (men or women according to Wikipedia). Anything above 300 as her mythical diary suggested, would move her to the top spot. Her problem was she got greedy. She should have kept it to peasant girls (why no boys?) and she could have kept going for years. Take that glass ceiling..

I know life expectancy wasn’t that great back then but dying in her sleep at 43 while under house arrest sounds a little suspicious to me.

Keep in mind it was 80 charged not 80 proven. I’d guess that 16th century Hungary (or England for that matter if you think of Anne Boleyn) had rather different standards of evidence than even 21st century Hungary let alone western systems of justice.

The notion of getting greedy seems to be an element of human behavior particularly for people in positions of power even today. They think of themselves as untouchable and they often are.

As for my inference from your final statement that she might have been murdered, that’s interesting speculation and certainly not unreasonable but something I haven’t investigated so I have to keep it as an unresolved mystery in the end much as the other parts of her biography.