In the time before humans.

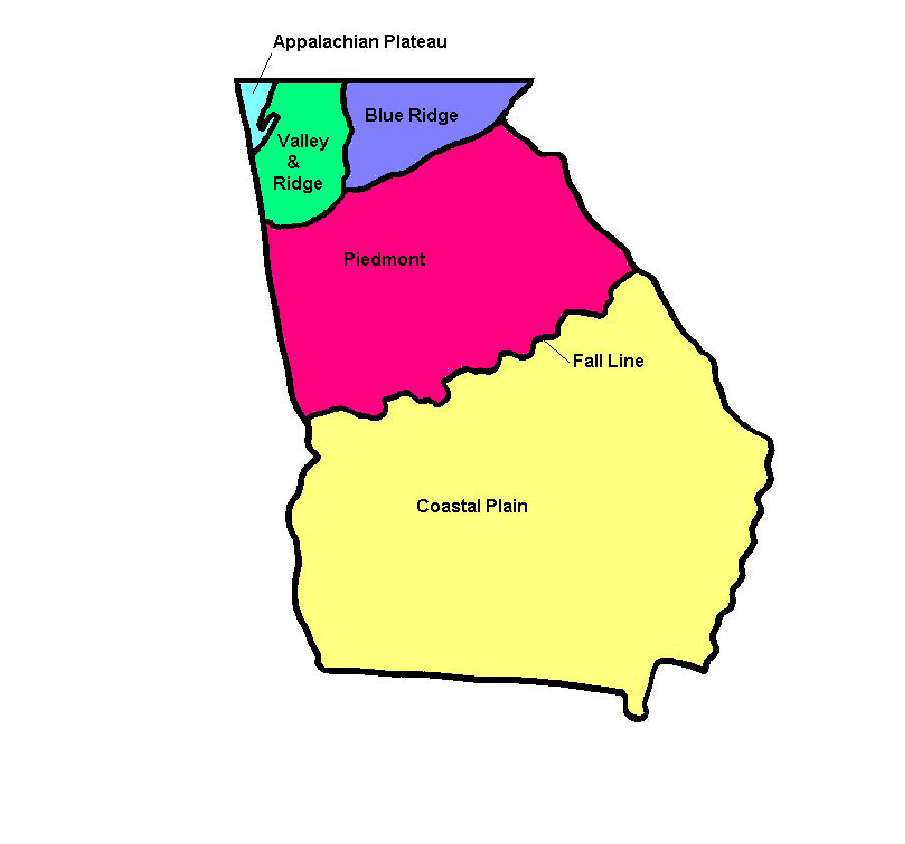

If we took the WABAC Machine far enough into the past, we would see that many of the same forces that shaped Montreal and eastern Canada also played a part in shaping the geology of the southeastern United States. Those of you who read the first Montreal supplement and went on to read about the the period of mountain building known as the Grenville orogeny know that Grenvillian rocks can be found as far north as Montreal and, while not as common, as far south as Atlanta. I won’t take us that far back but it’s noteworthy that the oldest rocks in the state of Georgia are found in the geologic zone called the Piedmont which, perhaps not coincidentally, is the zone where we also find the city of Atlanta.

[(Map from www.New Georgia Encyclopedia.]

[(Map from www.New Georgia Encyclopedia.]

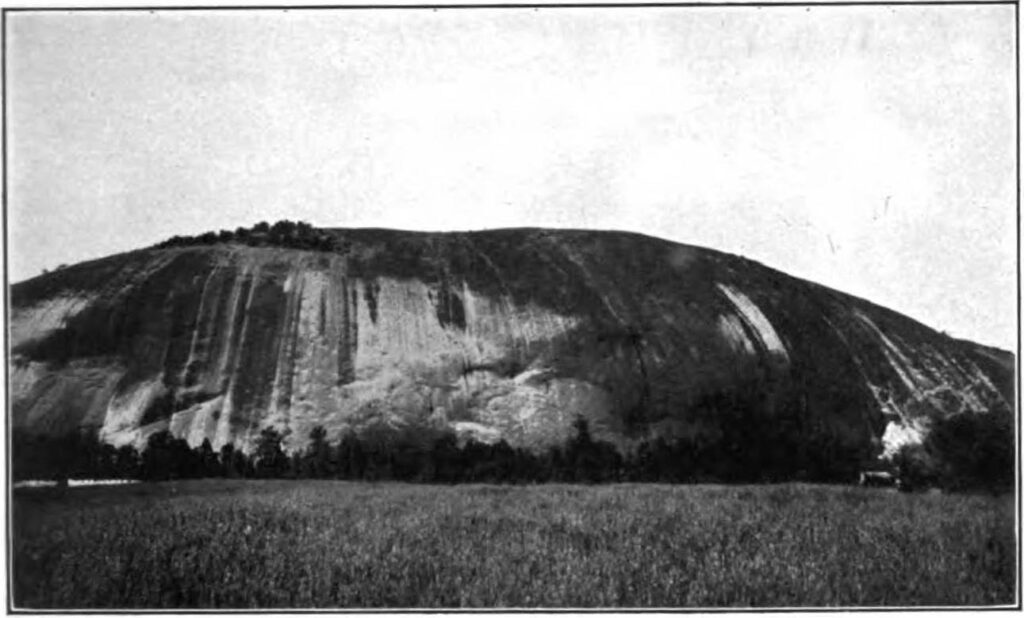

You may recall that in the initial Atlanta and me post I mentioned going to Stone Mountain on my first visit to Atlanta. A large scale intrusion of granite accompanied the Grenville orogeny and since Stone Mountain is the largest piece of exposed granite east of the Mississippi River one might reasonably conclude that it is a remnant of that age. As it turns out, while it’s reasonable, it’s also an errant conclusion.

Stone Mountain granite is igneous rock that collected and solidified some 16 kilometers below the surface some 300 million years before present (BP) during the Pennsylvanian subperiod of the Carboniferous Period which is also called the Age of Amphibians. The rock was gradually exposed through the processes of uplift and erosion over a period of some 285 million years. Its current shape arises from a process called exfoliation which is the gradual stripping away of thin layers of stone that remove pressure from the granite and allow its expansion in all directions.

The sculptor originally contracted to carve the mountain was one Gutzon Borglum who was fired from the project before the carving of the mountain commenced. (Borglum, you might recall moved on to carve another mountain in South Dakota.) In Borglum’s time, it looked like this:

[From Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

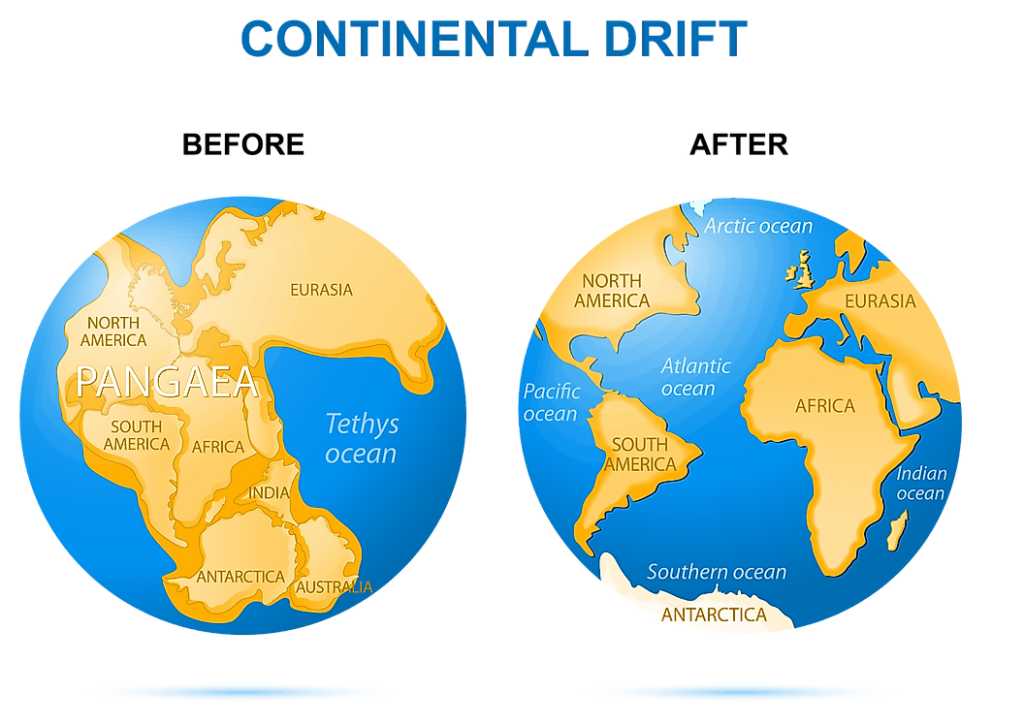

Although the Piedmont, with its ties to the Grenville orogeny, is the oldest of Georgia’s five geologic regions, most of its present makeup is more closely associated with the Alleghenian orogeny that started some 325 million years BP and continued for a period of 60 million years. The Alleghenian marked the end of the Appalachian orogeny which was powered by the collision of North America and Africa. In this late stage, all the previously formed Appalachian components collided to lift mountains that were between four and seven kilometers high and to form the supercontinent Pangaea. But as so often happens in such close relationships, time and erosion took its toll on the mountains and the lands of Pangaea lost interest in each other and began to slowly drift apart.

[Comparative map From WorldAtlas.]

Many Rivers.

Before I wrap up this ever so brief look at the geological forces that shaped Atlanta and the surrounding region, I’d like to provide a brief explanation of the rather odd marker on the Georgia Encyclopedia map that’s called the “Fall Line” and that separates the Piedmont from the Coastal Plain. I find it noteworthy because it’s the only regional boundary that is specifically identified.

While its size makes up nearly half of Georgia’s land area, the Coastal Plain is the youngest of its geologic zones. Here, sedimentary rocks of the Cretaceous period overlap the metamorphic and igneous rocks of the Piedmont.

The fall line is a geological boundary, about twenty miles wide, running southwest to northeast for about 250 miles across Georgia from Columbus to Augusta. While the change in elevation isn’t dramatic, in places it rapidly loses elevation from the north to the south. Rivers flowing across the fall line create a series of waterfalls.

Through the eighteenth and early part of the nineteenth centuries, rivers were a major means of commercial transportation. The fall line marked the upstream limit of navigable river travel and cities such as Columbus on the Chattahoochee River and Augusta on the Savannah River were known as “fall line cities.”

[Chattahoochee River By Joseph Jay/Flicker.]

Ships had to disembark and reload their cargo onto flatboats and barges on the other side of the falls in order to continue their journeys.

Later, fall line waterfalls powered mills and eventually hydroelectric dams. Today, the reservoirs created by those dams are used more for recreation than for power production. Additionally, by the middle of the nineteenth century, railroads came to replace river transportation as the main mode of commercial traffic. This change would give birth to a new city in Georgia when its location was chosen in 1836 to be the terminus of a rail line connecting the region to the U S Midwest. That city would be called Atlanta .

Before we get to the next post and the arrival of humans, let’s take a Jimmy Cliff break.