Good Tuesday morning! After eight days, we’re saying farewell to Norway. It’s a drive of about 120 kilometers to the Swedish border and 525 to Stockholm. Based on the roads, a stop to change our Norwegian kroner to Swedish kronor, and a stop for lunch we should arrive in the Swedish capital late in the afternoon.

In an earlier post, I promised I’d discuss the system of Scandinavian social democracy and now seems like a good time to start. Before I wade into those waters, one aspect of Scandinavia’s relationship with the rest of Europe should be apparent from the opening paragraph of this post. They’re not part of the single currency, the euro. Okay, it’s apparent that two of them aren’t but Denmark completes the trifecta.

Now, I should note that while Denmark and Sweden are part of the European Union (EU), Norway’s voters have twice rejected full membership. The reasons are likely complex and probably wrapped up, at least in part, by the country’s wealth from its oil and gas sales and the sense that, with most trade barriers already lowered by their participation in the Schengen Agreement, they had little to gain by accepting full participation.

[Map from the BBC.]

Remember also that Norway has limited agricultural resources. Their farmers receive significant government subsidies that are unaffected by Norway’s participation in the European Economic Area and the European Free Trade Association. These farmers likely feared they’d lose those subsidies with full EU participation. The same applies to Norway’s fisheries.

Psychologically, the thought of European unity might have also been a difficult element for Norwegians to grasp. Some still feel stung by the humiliation of the Nazi invasion and the idea becomes more complicated because the political party headed by Vidkun Quisling was called the National Unity party.

Finally, before starting my look at Scandinavian social democracy, I want to show you something I found interesting about riding a bus through much of the loop I showed on the map in the previous post.

This is not a back road; this is the main road between Oslo and Stockholm. What I want you to notice is not the rain on the window or even the moose crossing sign but rather the fact that this is a two-lane road. Very few of the roads we traveled had more than a single lane in each direction. Traveling along these two-lane roads with little or no advertising, that are not lined with fast food restaurants and strip malls and no – or I should say very basic toilet facilities – gave me the sense of being off the beaten path and thus evoked some memories of the Mississippi River journey I took last year.

The truth is that in this way, Norwegians are quite practical. There are no Norwegian automakers and they appear to have a limited trucking industry exerting pressure on the government to expand the highway system. Combine this with the country’s population of a bit over five million people and the fact that many of the roads become impassable through the winter months and you add factors that limit the demand for highways as we think of them in the States.

On the other hand, the Norwegians seem a bit like dwarves in the sense that they like to tunnel. Drive or train through Norway and you’ll almost certainly spend time in tunnels and observe that they are busily blasting through more mountains. Though these efforts considerably shorten the time between destinations, they concurrently limit the amount of the country you actually see. Or, as Frederick might put it, “You get to see the country from the inside and the outside.”

Today’s Lesson:

What is Nordic capitalism? I think academics would describe it as a system of competitive capitalism that seeks to promote social mobility and maintain low levels of income inequality while ensuring the universal provision of human rights and services.

While each of the Nordic countries takes slightly different approaches to achieving these goals, certain common features emerge. They combine a large public sector with a generally strong free trade and non-protectionist view of the private sector. They provide generous public and other welfare benefits while encouraging a culture of individualism. Critically, their governments are generally considered to be among the best run and most transparent in the world.

So, while we’re at it and since the issue of voting rights has again bubbled to prominence through the roiling waters of American politics, and, since we’re in Sweden, let’s pour some attention onto its system of government and elections.

Sweden operates as a parliamentary democracy with general elections held quadrennially. The legal voting age in Sweden is 18 making over seven million people (of a total population of 9,650,000) eligible to vote. Voting isn’t compulsory but over the last five election cycles average voter turnout has been nearly 83 percent. (Norway has averaged over 77 percent and Denmark over 86 percent – and yes, I looked that up on the website of the Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.) Sweden grants suffrage to all Swedish citizens aged 18 or over who are, or previously have been, residents of Sweden.

Taking the process a step further, the Swedes make it easy to vote. They have an automatic enrollment system that tracks every citizen’s name, address, birth, and marital status. Unlike the U S which purports to be a beacon of democracy and freedom where voters need to prove their eligibility, the Swedish government sends proof of registration material to the homes of every eligible Swedish citizen in the national database. The number of votes declared as invalid in these countries generally hovers around one percent.

As a parliamentary system, Swedish elections employ the principle of proportional representation to ensure that seats are distributed among the political parties in proportion to the votes cast for them across the country as a whole. The sole limitation is that a party must receive at least four percent of all votes in the election to gain representation in the Riksdag, Sweden’s unicameral legislature.

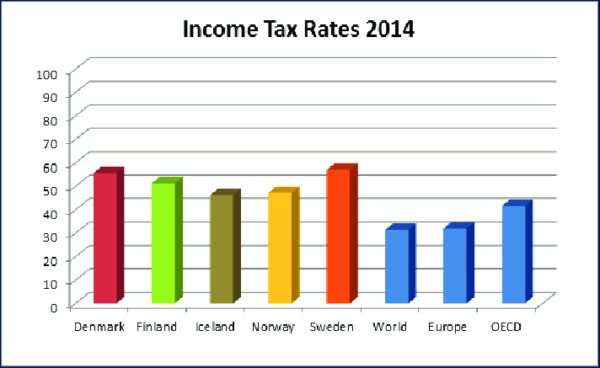

Returning to the idea of Nordic capitalism, anyone would agree that all of these countries are also characterized by heavy taxation.

[Graph from Researchgate.]

When local, municipal and national taxes are combined, marginal income taxes in Sweden peak at nearly 60 percent, there’s also a significant payroll tax and a generalized value added tax or VAT of 25 percent. Total tax revenue is between 45 and 48 percent of GDP while that number is closer to 25 percent in the U S. Low levels of defense spending help support these social programs. Sweden spends about four percent of its government budget and 1.1 percent of it’s GDP on defense. The comparable figures for the United States are 17 percent of its budget and nearly four percent of GDP..

Here are some of the benefits the system provides:

Free public education from kindergarten through a university degree (Sweden has three private universities.)

Nearly free health care. Swedes have an annual health care copayment of about $130 and about $250 for prescription drugs.

A base public pension beginning at age 65 for all Swedish adults that is income adjusted.

The elderly are encouraged to live in their own homes for as long as possible. The government provides support including meal delivery, cleaning and shopping assistance, and transportation services. Senior housing and retirement homes are also available for those who need more support. Costs are largely subsidized by the state.

As I noted above, each of the Nordic countries uses slightly different approaches to both benefits and taxes while sharing a broad commitment to social cohesion, reducing poverty and safeguarding individualism. Certainly, some individuals (especially in Sweden) complain about the high tax rates but in a 2013 United Nations published World Happiness Report, Nordic countries ranked highest on the metrics of real GDP per capita, healthy life expectancy, having someone to count on, perceived freedom to make life choices, generosity, and freedom from corruption.

We crossed the border a bit more than an hour ago and will stop for lunch in Karlstad. The train station was just a block from the hotel where we ate. I took this picture

for old times sake recalling my Beijng to Saint Petersburg trip.

When we arrived at our Stockholm hotel, the Clarion Hotel Sign, in the early evening, the lobby and lobby bar were abuzz with thumping disco and EuroPop. It’s Pride week in Stockholm and our hip, modern hotel seemed to want to be at the center of the festivities. The staff wore tee shirts that declared, “We don’t care who you are or what you do.”

I could only hope that this attitude extended to the guests as well as the staff. My room had an inside view just as it had in Bergen. And, just as had been the case in Norway, any open blinds opposite one another would have, shall we say, an unobstructed interior view.

The time has now come to retire and prepare for a full day of activity in the Swedish capital tomorrow.