A real Downie of a day – the Beaumarchais edition – part 2

New Intrigues.

In April 1775 Beaumarchais went to London with a mission from King Louis XVI – to reach a settlement with a certain Chevalier D’Eon. D’Eon was attempting to blackmail Louis XVI by revealing to the British correspondence between himself and the new king’s grandfather Louis XV (the present Louis’ father had predeceased his son) about a possible invasion of England to avenge the losses codified in the 1763 Treaty of Paris that had ended the Seven Years War. (Don’t confuse this with the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the American Revolutionary War – or any of the other Treaties of Paris, for that matter.) This part of Beaumarchais’ mission was effectively an encore of a performance he’d made twice before.

The Foreign Minister for Louis XVI, Comte de Vergennes, was a staunch royalist devoted to the cause of restoring the greatness of the Bourbons and was responsible for recommending Beaumarchais for this role. It was Vergennes who added to it the part of international spy. Bear in mind that the Battle of Lexington and Concord – generally considered the first skirmish of the American Revolutionary War was fought on 19 April 1775.

[The Battle of Lexington painting by William Barnes Wollen – Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

Expecting that any restoration of the Bourbons would require another war with the British, Vergennes believed he needed as much information as possible on the real state of Britain’s relationship and military status with its recalcitrant American colonies. Beaumarchais, who had friends both within the government such as Foreign Minister Lord Rochford and associations with prominent leftist Whigs such as John Wilkes who supported the American cause, was well positioned to gather information from both sides.

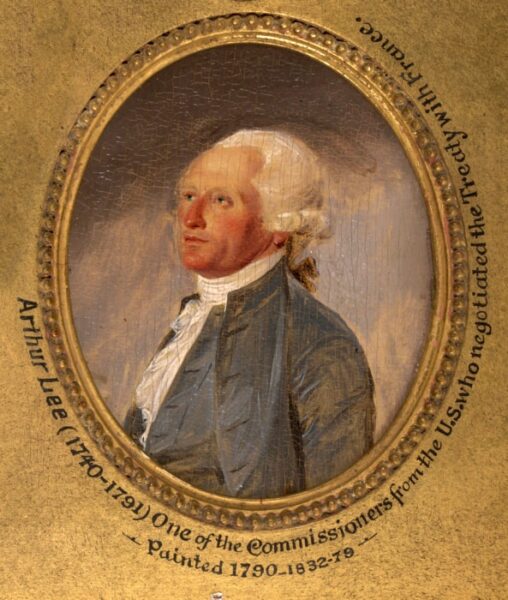

Through his association with Wilkes, Beaumarchais met Arthur Lee an American diplomat, correspondent, and negotiator.

[Portrait of Arthur Lee from Americanrevolution.org – Public Domain.]

Lee, who was a major proponent of American resistance to the British, and who wrote a number of influential pamphlets opposing slavery and British continental and colonial policies, eventually helped turn Beaumarchais into not only an outspoken supporter of the American position but an advocate for French intervention.

The possibility of French intervention was hampered by several factors, however. Foremost among them were the country’s remaining debt from the Seven Years War and a military badly in need of modernization. Beaumarchais, together with Vergennes and others in the French government proposed a solution that would address both issues while allowing the French to maintain the appearance of neutrality.

Beaumarchais set up a firm he called Roderigue Hortalez et Compagnie with a nominal raison d’être of trade with the West Indies. In reality, it was a front for a company that would buy perfectly serviceable munitions from the French government on credit, sell them to the Americans, and then reimburse the government. In this way, the government could dispose of its outdated surplus equipment while earning a tidy profit that it could then use to purchase or manufacture new arms.

Infected with an over-sized sense of theatricality, Beaumarchais attacked his newest role with the fervor of an adolescent wooing his first crush. With the initial capital supplied by a loan of 1,000,000 livres from the French government, a second million provided two months later by Bourbon ruled Spain, and a third million raised from a group of French merchants, Hortalez and Company was ready for business. He returned to Paris where he rented a large building at 47 rue Vielle du Temple called the Hôtel des Ambassadeurs de Hollande,

since it had formerly been the Dutch Embassy. Here he set up the firm’s offices, moved his residence and family into the same building, and sought a responsible American agent with whom to do business. (The famous doors with the Medusa heads must have been off for repairs.)

(The house at 47 rue Vielle du Temple was not Beaumarchais’ final residence. He would build another, more spectacular mansion a bit more than a kilometer east of this location. Here’s how Downie describes them in Paris, Paris:.

Inheritances and settlements, plus real estate speculation and a controlling interest in Paris’ first-ever water utility have made Beaumarchais fabulously rich. Known as the “Mansion of Two Hundred Windows,” Beaumarchais’s estate is a parvenu’s paradise, with a semicircular colonnade, temples to Bacchus and Voltaire, a Chinese humpback bridge, and a waterfall. The Bastille rises to the south, its towers and bastions an ominous theatrical backdrop.

Perhaps fittingly, even his grave was not his final resting place. Writing of Beaumarchais’ death in 1799 Downie adds,

There’s nothing left of the Mansion of Two Hundred Windows and its grounds, where Citizen Beaumarchais spent the final years of his life, still rich and full of fire but no longer a hero. He died in the last year of the eighteenth century, on the cusp of the modern age, and was buried in his garden near Voltaire’s temple on the edge of the Marais. The final irony, a postscript to this extraordinary life, is that, before the estate was demolished to make way for the Canal Saint-Martin and Boulevard Richard Lenoir, King Louis XVIII’s men dug up the freethinking playwright’s bones, in 1822, and moved them to Père Lachaise, a cemetery named for a Jesuit priest. Even in death the itinerant iconoclast knew no rest.

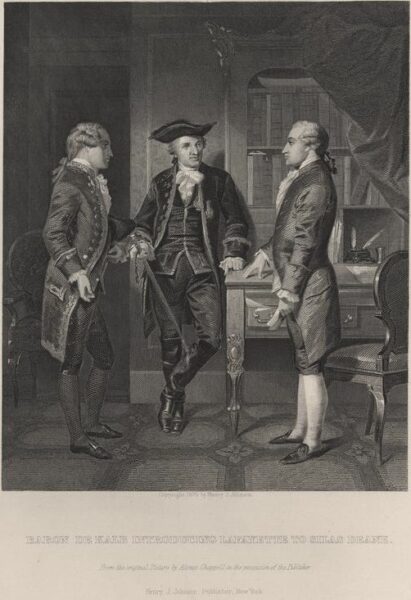

Beaumarchais’ American agent turned out to be Silas Deane (who would later negotiate the 1778 Treaty of Alliance between France and the nascent United States).

[Baron de Kalb introduces Deane to Lafayette – Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

The pair signed agreements on 20 and 22 July stipulating that Beaumarchais would make his goods available to Congress on a one-year credit and that Congress would make payments in kind. Tobacco, indigo, and other colonial goods would all be acceptable.

Beaumarchais, always in search of a profit, immediately began chartering and provisioning ships. He induced Donatien le Rey de Chaumont, intendant for supplying clothing to the French army, to become one of his partners. Chaumont gave the firm a credit of one million livres and undertook to supply copious amounts of clothing. In less than a year, Beaumarchais accumulated 200 field pieces, 300,000 muskets, 100 tons of powder, 3,000 tents, and uncounted rounds of ammunition. He also had a blanket, a pair of shoes, and two pairs of wool stockings for each of 30,000 men and was amassing it all in Le Havre to prepare for shipment.

Unsurprisingly, British spies noticed this. They summoned Vergennes who not only professed ignorance but pointed to his bona fides as a staunch royalist – how could he possibly be involved with supporting such rebels? But there was another problem. The massing of sailors in Le Havre who, while waiting for favorable conditions to set sail, were openly bragging about sailing to America only added to the pressure on the French government which eventually issued ordinances against the smuggling of war supplies.

Beaumarchais now had to operate more covertly. He had to become not just an arms dealer but an arms smuggler – a black marketeer – if you will. Unfortunately, he then went about blowing his own cover when he noted a local theater company’s intent to produce his play Le Barbier. Despite his use of a pseudonym, he began attending rehearsals and too authoritatively instructing the actors and director in aspects of its production.

Lord Stormont, the British Ambassador, went to Vergennes armed with evidence of the involvement of a known confidant of the King and the Foreign Minister obviously trafficking war contraband. Vergennes had no choice but to block the departure of three ships that Beaumarchais had prepared.

After more than a month’s delay, Vergennes quietly signaled to Beaumarchais that the ships could sail if they departed Le Havre under cover of night. Beaumarchais took the bold step of ordering his ships to sail directly for Portsmouth, New Hampshire rather than to the West Indies as initially planned. The supplies, which arrived in April 1777 and were delivered to the northern army under Horatio Gates, were crucial to the American victory at Saratoga in October of that year.

[Surrender of General Burgoyne – from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

It was that victory, proving that the Americans could match blows with trained European armies, that gave the French enough confidence to intervene directly.

Beaumarchais continued sending supplies throughout the summer of 1777 though he returned to using the more cautious and circuitous route of first sending the material to ports in Haiti. Those shipments, accumulated by Beaumarchais and overseen by Deane constituted almost all of the military goods reaching the rebelling colonies in 1777 and 1778. Without the efforts of these two men, the United States might never have survived its infancy.

Perhaps an actualization of the butterfly effect, had Beaumarchais not won his case against Jean-André Lepaute over the invention of the escapement, Pierre might never have come to the attention of Louis XV. He might never have been asked to make that finger watch for Madame de Pompadour and had he not made that watch that so pleased the king that opened access to the court and all that followed, the United States of America might have never come to be.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026