A Not So Mellow Yellowstone Afternoon

Although not quite a canyon wall cliffhanger, my previous post ended as I was driving south toward Old Faithful to see yet another different facet of the park.

Visiting the Midway.

When our ranger guided south rim walk was done, some folks set off for more hiking – of which there was plenty even with some of the more famous trails such as Uncle Tom’s Trail (named for H F “Uncle Tom” Richardson not the Harriet Beecher Stowe character) and viewpoints closed. I, however, wanted to see one of the more dramatic shows in Yellowstone and, without the power of flight, it was more than 30 miles away.

My goal was the very practically named Midway Geyser Basin found about halfway between the Upper Geyser Basin – home to Old Faithful – and the Lower Geyser Basin home of Firehole Lake and the Great Fountain Geyser. I wanted to visit Yellowstone’s largest hot spring called Grand Prismatic and it’s not merely its size that makes it one of the most remarkable sights in the park. When he first encountered it, Ferdinand Hayden, who led the 1871 expedition, wrote this:

Nothing ever conceived by human art could equal the peculiar vividness and delicacy of color of these remarkable prismatic springs. Life becomes a privilege and a blessing after one has seen and thoroughly felt these incomparable types of nature’s cunning skill.

Even if I’d never seen a picture of Grand Prismatic prior to my time in the park, these words alone would make it worth the effort. Along the way, I passed other geyser fields. I took the picture below through my car window which accounts for the blurriness but what you see has some bearing on what I’ll see so I thought I should share it.

Two elements combine to create the best experience of Grand Prismatic. One is a clear blue sky and the other is elevation. I managed the second but, as the photo above shows, the other was unattainable.

Whether you park along the road or in the usually crowded parking lot, you have to cross the Firehole River to reach the basin. Once there, a sign instructs visitors to stay on the boardwalk because although the ground appears lifeless, it’s actually teeming with a miniature bacterial forest and treading on it would contaminate it. The first attraction along the boardwalk is the Excelsior Geyser pool and crater.

(Believe it or not, I’ve enhanced the color in this photo. The original is on display in the folder linked below.)

Although it’s little more than a hot spring today, the Excelsior Geyser below the spring was once an active gusher. In the late 19th century, it regularly spouted eruptions between 250 and 300 feet before going dormant for most of the 20th century. It erupted for two days in 1985 but has been quiet since. However, given the ever-changing nature of Yellowstone’s geologic underpinnings, a resurrection of activity is certainly possible.

At this juncture, you can continue with the general flow of pedestrian traffic up to the Grand Prismatic or turn right, pass two other springs on the site and save the best for last. While I followed the former, I’m going to take you on the latter.

Following this counter-clockwise path, the first stop is called the Turquoise Pool. I’ve seen photos where this pool does, indeed, appear turquoise but that wasn’t the case for me. Likely the result of the ash in the sky, the day of my visit, the pool was rather drab.

Now, the Opal Pool, was much more intense.

The final stop is the Grand Prismatic itself. Here’s a look from the satellite (and I urge you to look at the enlarged view).

I’ll have some close ups and a shot from elevation, too but before I post those, let’s explore its traits and the biology that makes it so colorful.

Colors of the prism.

With a diameter of 370 feet, the Grand Prismatic is not only the largest hot spring in Yellowstone NP, it’s the largest in North America and third largest in the world. Only Frying Pan Lake in New Zealand and Boiling Lake in Dominica are larger. (Not only does the name Boiling Lake seem to have jumped off the pages of The Princess Bride but it’s in the brilliantly named Morne Trois Pitons or Three Dreary Peaks National Park and is adjacent to the Valley of Desolation.)

The colors of the Grand Prismatic begin 121 feet below the surface of the pool as water with an average temperature of 189° (or slightly lower than the 212° at which water boils) makes its way through cracks and fissures in the Earth’s surface in an unblocked flow rising – as all hot things do. Of course, as it rises, it spreads over the surface, the pressure slightly abates and the cooler water, as all cool things do, sinks. This cyclic process creates distinct temperature zones radiating from the pool’s center.

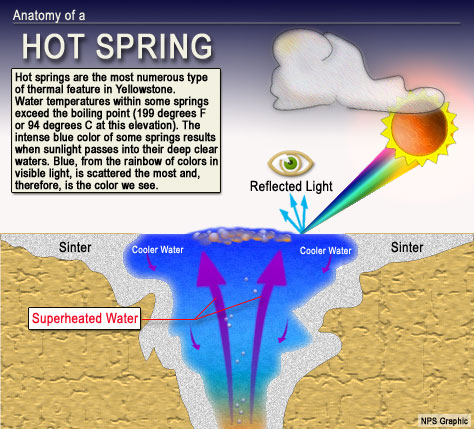

Surprisingly, even at the high temperature and pressure, a few organisms manage to exist by feeding on inorganic chemicals like hydrogen gas. The relative scarcity of living things at that depth and temperature generates the deep blue color of the center of the spring. (Also, blue is the color that scatters most in visible light.)

[Image from https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/images/hotspring_works.jpg]

As the water cools and becomes more “hospitable” several life forms move in. Each distinct temperature zone creates an environment allowing specific bacteria to flourish within that zone but not outside it. These different types of bacteria give the spring its prismatic colors.

Even if you haven’t enlarged the image, you should be able to see that the first band encircling the blue center is yellow. In some ways, the Synechococcus cyanobacteria that occupy that band and that are responsible for its yellow color exemplify the ubiquity and tenacity of life. The water temperature of 165 degrees is considerably hotter than the 145 to 150 degree temperatures in which this bacteria normally lives and thrives. But that’s not the only habitat stress this seemingly unfortunate Synechococcus is fighting.

The satellite image shows that the immediate area around the spring is treeless. The lack of shade would be stressful for these bacteria at sea level but because the spring sits at 7,270 feet elevation the bacteria are exposed to an abundance of harsh ultraviolet light. And still, they’ve adapted.

Here’s how. As they undergo photosynthesis, instead of producing large amounts of chlorophyll, which would, as we know, turn green, they produce high levels of an accessory pigment known as a carotenoid. These carotenoids capture light at harsh wavelengths, convert the light into chemical energy and pass that energy to chlorophyll pigments. In the conversion process, carotenoids produce red, orange or yellow pigments and, because in this instance there’s more carotenoid than chlorophyll, one of those becomes the dominant color. Interestingly, the yellow color that Synechococcus produces is beta-carotene – the same pigment that, at higher concentrations, turns carrots orange.

As our eyes continue moving away from the center, the temperature continues cooling, allowing more diverse populations in the community alongside the Synechococcus. Principally, it’s a type of bacteria known as chloroflexi. Nearly all types of chloroflexi are photosynthetic but two suborders of this class of bacteria have different physiological characteristics. Each suborder is characterized by chlorophyll and carotenoid profiles that are consistently absent in the other suborder. The orange color we see is a composite of the chlorophyll and carotenoids collectively produced by the various types of bacteria.

At a temperature of about 131 degrees, the outermost ring is the coolest and, as one might expect, home to the most diverse community of bacteria. As even more organisms are able to live in the outermost ring, the mix of their various carotenoids produces the dark red-brown of the outer edge. Up close under an ashy sky, the spring looks like this:.

However, the best way to get the full impact of Grand Prismatic is to see it from above and there are two ways to get the elevated view. Both entail a steep and mildly strenuous walk. On the satellite view above, there’s a spot across the Grand Loop Road labeled Midway Bluff. If you want to take the path less traveled for your elevated view, this is your choice. However, be forewarned, as I was by this article, that this is a “social path” meaning it isn’t maintained by the NPS and isn’t marked.

The other route begins at the Fairy Falls Trailhead about three-fourths of a mile south of the Midway Geyser Basin. The path, which is clearly visible in the satellite photo, is well maintained but it’s also a steep climb. This is the path I chose and, after I huffed and puffed my way to the top,

I was rewarded with this view. You can see an enhanced version of the photo where I tried to approximate the view on a clearer day in this folder.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026