The Tucson wrap-up.

In the historical narrative I started before lunch, I’d reached the overlapping moment when Americans in the east were drafting a declaration and fighting a war of independence from England while in Tucson, Spaniards, under the leadership of Hugo Oconor had started construction on the Presidio marking the founding of the city as we know it today.

Let’s jump ahead 50 years or so and note that in 1821 the territory became part of the state of Sonora after Mexico gained its independence from Spain. Then, in 1836, Texas won its war for independence from Mexico and President Andrew Jackson quickly established diplomatic relations with the fledgling republic.

This exacerbated the tension between the United States and its southern neighbor. The situation remained tense but static until April 1844 when President John Tyler concluded the Treaty of Annexation – a treaty the Senate initially failed to ratify. With the help of President-elect James Polk, Tyler pushed a joint resolution through both houses of Congress on 1 March 1845 and Texas was admitted to the union on 29 December of that year.

Mexico had threatened to declare war if the US annexed Texas but because of weakness in its economy and a number of internal conflicts, it didn’t follow through. Still, several months of border disputes followed and in July 1845, Polk began a two-pronged effort – military and diplomatic – to settle them. First, he sent Zachary Taylor and a 3,500 man army to hold the disputed land between the rivers Nueces and Rio Grande. Then, in November, he sent Louisiana Congressmen John Slidell to Mexico to negotiate the purchase of territory.

The negotiations failed and on 13 May 1846, the United States declared war on Mexico. By September 1846, Taylor had pushed the Mexican Army out of Texas and had captured the Mexican city of Monterrey. The fighting continued and in September 1847, the American Army captured Mexico City. That’s when Nicholas Trist negotiated the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo. The treaty, signed in Mexico City on 2 February 1848, ended the American-Mexican War. The terms included Mexico ceding more than half a million square miles of territory for a payment of a bit more than $18 million. Despite substantial opposition from an expansionist Senate that wanted to keep the money, the body ratified the treaty on 10 March 1848.

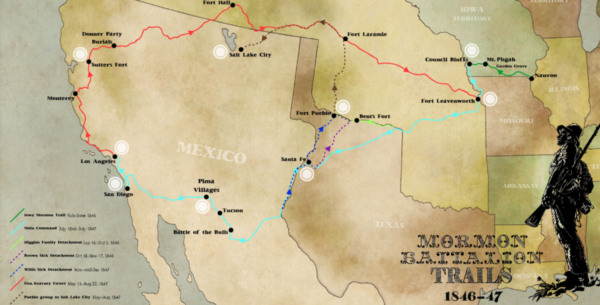

I introduced you to the Mormon Battalion during my visit to the This is the Place Memorial. (This was the unit formed in June 1846 after the negotiations between President Polk and Jesse Little that’s honored at the This is the Place Historical Park.) In their march to California, the battalion “captured” what had become the town of Tucson in December of that year. There was no real battle and the tired troops were more interested in trading for supplies than they were in fighting the Mexicans. You can see the principal routes on the map below taken from https://history.churchofjesuschrist.org.

In addition to what they acquired through trade, they confiscated about 30 bushels of wheat from some 1,500 stored in the town. When they continued their march westward to California, the inhabitants and Mexican forces simply strolled back into the city and Tucson again quickly fell under Mexican control where it would de jure retain that official designation for eight years but, de facto, for ten.

The Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo didn’t quite settle all the disputes between the US and Mexico. For example, both countries claimed the Mesilla Valley (a significant stretch of land along the Rio Grande reaching from Laredo, TX to Las Cruces, NM). The Mexican government also made claims against the US for attacks launched by Native American tribes which, in the treaty, the Americans had agreed to prevent. In an interesting inversion to the current situation, US-Mexican tensions were also aggravated by the persistent efforts of American citizens illegally entering Mexico. In this case, the Americans weren’t seeking jobs but were (not so surreptitiously) attempting to incite rebellions that would yield still more territory for the north.

In September 1853, hoping to settle the situation, President Franklin Pierce ordered James Gadsden, his Minister to Mexico, to negotiate a purchase of land with General Santa Ana (who needed the money to fight rebellions in other parts of Mexico). The US and Mexico completed the Gadsden Purchase on 8 June 1854. The United States agreed to pay $10 million for a 29,670 square mile portion of Mexico that later became part of Arizona and New Mexico. In Arizona the purchased land was south of the Gila River (that runs east to west from just south of Phoenix to Yuma).

And still, not all the disputes were settled. According to the US State Department’s history website, “the treaty failed to resolve the issues surrounding financial claims and border attacks. However, it did create the southern border of the present-day United States, despite the beliefs of the vast majority of policymakers at the time who thought the United States would eventually expand further into Mexico.” It wasn’t until March 1856 that the American military took formal control of the Arizona territory.

This, of course, left the territory vulnerable to the assault from John Baylor. Baylor, as you might recall from the history of the Battle of Picacho Pass (recounted here), had led a unit of Texas cavalry into the territory and declared the Confederate Arizona Territory with Tucson as its capital.

The web the Clifton spins.

When I planned the trip I decided I wanted to have a different experience of Tucson on my last night than I’d had the first two. So, rather than returning to Carolyn’s Air BnB room, I chose to stay at the Downtown Clifton Motel. I suspected I’d succeeded as soon as I pulled into the parking lot.

The hotel is in the Armory Park Historic Residential District and this photo not only encapsulates the spirit of the hotel but of the neighborhood. At least for now.

As I walked through it, the neighborhood felt to me somewhat like the Adams Morgan neighborhood in Washington, DC. Not today’s Adams Morgan, though, but rather Adams Morgan as it was some decades ago. Walking around Armory Park in Tucson, I sensed a neighborhood on the cusp of gentrification. I fear it could be a very different place in five or ten years.

When I checked in, in addition to my room key, they handed me a card that, measuring 3 1/8″ by 6 1/8″ was only slightly larger than my mobile phone. Like the mural, gravel parking lot, and the courtyard, this card also tells you a lot about the Downtown Clifton. I scanned it and reproduce it here because I think you need to read it yourselves (remember you can enlarge it by clicking on it).

The room is pretty basic and if you want, you can read my Trip Advisor review. As I mentioned in an early post, I thought Tucson quite pedestrian friendly and there are plenty of places you can walk to from this motel. For example, the El Presidio neighborhood is about three quarters of a mile and the Fourth Street district a bit more than half a mile. As for the Armory Park neighborhood itself, you can have a look at some eye catching parts of it (plus the last few pictures I took in Tucson) here.

When I returned my rental car, I’d driven an astounding 3,907 miles. I find this noteworthy because in the two years since I leased my Chevy Spark, I’ve driven it a total of about 9,300 miles or about 4,650 miles per year. Put another way, it means that in just more than two weeks, I’d done the equivalent of 10 months of the driving I do at home.

Although I had to sit through a nearly three-hour delay for my connecting flight in Chicago and didn’t get home until after midnight (so early Tuesday morning), there’s little else to say about the final travel day. Zicomo was happy to see me and, while I was happy to see him, I think I was equally happy to fall into my own bed.

I have another trip scheduled for late summer and I hope you’ll return when I recount that one.