Based on the end of yesterday’s entry, it shouldn’t surprise you that one of the doses of grandeur referenced in today’s headline is the Grand Canyon. This is where I’ll end the day but there’s some other grandeur to see along the way. So let’s hit the road. First stop –

Picacho Peak State Park.

For the most part, as soon as you get on I-10 headed north from Tucson, you can see Picacho peak which is about 50 miles away. The immediacy of its visibility isn’t because its summit is overly high – in fact, it only rises to about 3,374 feet above sea level or 1,000 feet from Tucson’s elevation. Rather, the surrounding valley is so flat and the peak is so isolated from other nearby mountains that it stands out. Its name is interesting, too. Wikipedia calls the name redundant stating, “”picacho” means “big peak” in Spanish.” My memory of Spanish tells me that big peak would be pico grande but there might be some slang or Native American-Spanish patois that makes the statement accurate – or maybe my memory is faulty.

Those of you who have read some of my other travel stories probably suspect that it’s not merely the peak that I found worthy of interest. And that suspicion would be correct.

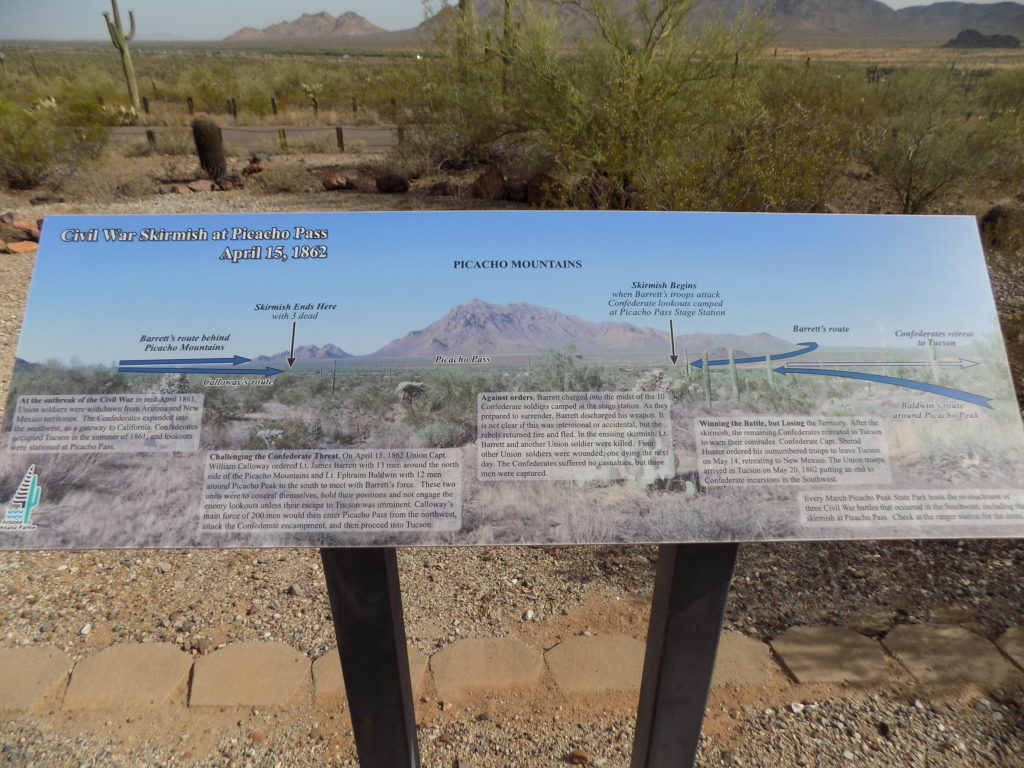

Historians expansively familiar with the American Civil War might recognize that the Battle of Picacho Peak is considered the westernmost battle of that conflict. (A sign in the park indicates a “skirmish” at Stanwick Station near present day Gila Bend which is about 80 miles west but apparently there wasn’t enough of an interaction to consider that encounter a battle.) Those among you who aren’t Civil War experts are about to get a history lesson so buckle up.

The story of the Battle of Picacho Peak begins in 1854 – some eight years before the fighting occurred. James Gadsden, then the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, negotiated the purchase of 29,670 square miles of what had been part of Mexico that would eventually become parts of Arizona and New Mexico. The Gadsden Purchase was intended to end most of the conflicts remaining from the American-Mexican war that had officially ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848.

Although the purchase was completed in 1854, the American military didn’t take control of the area until 1856 and they quickly became unpopular with both the Apache and the few white settlers who had staked claims in the area. It’s also important to note that in 1846 David Wilmot – a congressman and later senator from Pennsylvania – foresaw potential problems with the southwest so he tried to attach a rider to an appropriations bill stipulating “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist in any territory acquired by the United States in the war against Mexico.” Southern senators managed to block its passage. But this effectively set the stage for conflict.

The simmering conflict bubbled to the surface after the American Civil War began when, in July 1861, a force of Texan cavalry and Arizonan militia commanded by Lt. Colonel John Baylor conquered the southern New Mexico territory, including Tucson. On 1 August 1861, Baylor proclaimed the existence of a Confederate Arizona Territory, with Tucson as its capital and appointed himself permanent governor.

Baylor then sent Captain Sherrod Hunter to Tucson, which he occupied rather easily on 28 February 1862 after a freezing winter march. The truth is that Tucson, and its population of fewer than 1,000 people had been largely abandoned by the Union at that time leaving many of the Hispanic merchants, whose territory was subjected to regular Apache raids, with an unsympathetic view of the Union. Together with the Anglo population, most of whom had migrated from the slave states of Missouri and Texas, Hunter was more welcomed than resisted making his so-called conquest of Tucson a rather easy one.

With its new garrison of 75 confederates, Tucson was now the farthest point west in the Confederacy. As long as the Confederate forces helped to suppress the Indians, they enjoyed the support of the local civilians – some of whom had formed secessionist militias even before the official Confederate arrival.

Efforts by the Confederacy to secure control of the region and continue west to California to create an ocean-to-ocean Confederate Empire prompted a quick response from the Union and led to the New Mexico Campaign. (It’s worth noting that the events in Arizona represented the most complete takeover of Union territory the Confederacy managed during its existence.)

The Union response began when Brigadier General James H. Carleton led a force of approximately 1,400 Union troops from Fort Yuma, California across the Sonoran Desert to march on Tucson. When Hunter heard about the approach of the “California Column” he led his troops north to the Gila River where the skirmish at Stanwick Station (mentioned above) took place on 30 March 1862. This encounter slowed the Union advance enough for the Confederates to prepare to face them at Picacho Pass.

The forces that met there were, in reality, quite small. The Union detachment, led by Lt. James Barrett, consisted of 12 troopers and John Jones a civilian scout and Tucsonan. The Confederate force totaled 10 – nine Arizona Rangers and their commander, Sgt. Henry Holmes.

On 15 April 1862, the day of the battle, Jones had gone ahead of the rest of the detachment and reported that the Confederates were not ready for an attack. Barrett, in an act of hubris, ignored two suggestions by Jones – first that he encircle the Confederate troops and ask for their surrender – and then, if he decided to attack, he do so with his troops dismounted because the terrain was unfriendly to a horse mounted battle.

The object was to capture the entire Confederate picket allowing the California Column to launch a surprise attack on Tucson. The outcome was that three Confederate soldiers were captured while the rest were able to fight on for about an hour before withdrawing into the cover of the mesquite trees and arroyos at the base of the mountains. On the Union side, Barrett and two others were fatally shot.

The Battle at Picacho Pass had little significance. A bit more than two weeks earlier, Union forces had effectively won a major battle at Glorieta Pass in north central New Mexico by destroying their supplies. This forced the Confederates’ eventual retreat first to Santa Fe and eventually to Texas. Thus, by the time forces of the two sides met at Picacho, the Confederate campaign in the far west had already begun to collapse.

When the California Column reached Tucson on 20 May only 10 Confederate soldiers remained in the city because Captain Hunter had ordered a retreat to Mesilla a week earlier. As Hunter’s troops continued their retreat into Texas, a certain lore grew around the action because, facing repeated Apache attacks, they reportedly armed their Union prisoners in an effort to survive. With their arrival at the Rio Grande on 27 May 1862, the Confederate invasion of Arizona effectively came to an end although it didn’t officially mark the end of the Confederate Territory of Arizona.

Confederate troops continued fighting under an Arizona banner until the end of the war. Some Arizonans set up a “government in exile” in Texas and continued to send delegates to the Confederate congress.

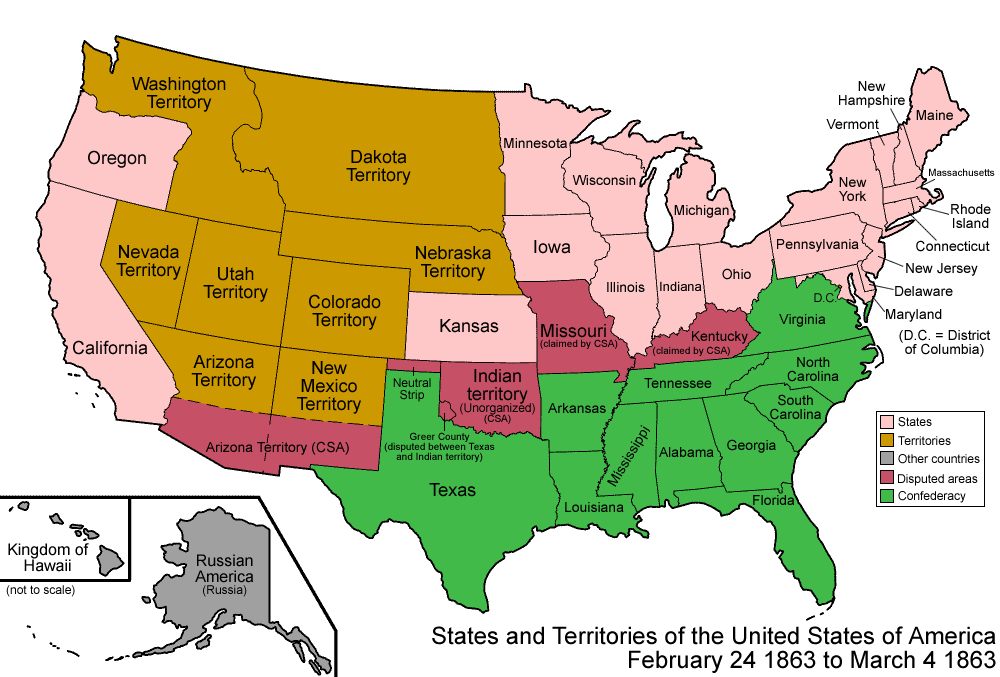

The Confederate withdrawal also played a significant part in drawing the map of the American southwest as we know it today. The Congress had longed feared that Arizona would join the Confederacy so they consistently derailed efforts to admit Arizona as a state. In February 1863, President Lincoln signed the Arizona Organic Act that would have divided the territory north from south along an east-west line that stretched from Texas to the Colorado River. It would have looked like this (from Wikipedia):

However, because this strip of land was too closely associated with the Confederacy, the north-south line we know today was established to more definitively separate Arizona and New Mexico. Arizona became the 48th state on Valentine’s Day (14 February) 1912.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Thank you for sharing my dear friend.

Went to Gettysburg today and then read Todd’s latest adventure to Arizona. Always enjoy learning about the Civil War and the history of this great country. Interesting that the Civil War made it all the way out west to Arizona.

Thanks Todd, and will be waiting to hear about your next trip out west.

Amazing sunset!

PS Once again, WOMEN getting it done!