First ruins of the day – the Big House.

Not too far north of Picacho Peak you can find the mysterious Casa Grande Ruins National Monument. In fact, one sentence in the brochure distributed by the National Park Service describes it that way reading, “The mysterious Great House was completed about 1350.” And herein is encapsulated the essential difference between nomadic cultures that frequently moved their settlements and settled cultures that rarely did and between cultures with written histories and those without.

Consider this from my trip to the Balkans last year: “Records show that construction on the walls surrounding the old city of Dubrovnik began in the ninth century and lasted for nearly 400 years.” Think about this for a moment. It means those walls were completed a century or more before this structure and we know more about them than we are likely to ever know about the Casa Grande Ruins. And yet, the culture of these ancient Sonoran Desert people is every bit as old, or perhaps older, than that of the Europeans. Still, between the antiquity and the mystery, it seemed a place well worth visiting.

(A word about terminology: In a minimal effort for economy, I will throughout, use the term Hohokam to refer to all these ancient peoples. This isn’t intended as a slight in any way but simply an effort to minimize my typing. Hohokam is a term used by archaeologists and is thought to be a misinterpretation of huhugam – the O’odham word for ancestors. Hohokam is not the name of a tribe or a people. It doesn’t appear in any of the other Sonoran tribal languages – Hopi, Zuni, or O’Odham but it has worked its way into common use.)

Some archaeological evidence suggests that the first hunter-gatherer tribes moved into the area sometime around 5,500 BCE. The introduction of domesticated corn from Mesoamerica appears to have prompted a gradual shift to a more settled farming existence. But the harsh conditions meant these early farmers had to find ways to use water from mountain run-offs and rivers to irrigate their fields which were generally close to the latter.

Of course, as their villages grew, the available farmland in proximity to rivers diminished. By the fifth century they began digging irrigation canals using techniques that they maintained for a millennium. The crops grown by the ancient Hohokam eventually expanded to include several varieties of beans and squash as well as cotton and tobacco. In addition to their crops, the Hohokam culture also made extensive use of many native plants and animals of the desert including cactus fruits, pads and buds, agave hearts (century plant), mesquite beans, and the medicinal creosote bush.

Farming gradually spread throughout what is today central and southern Arizona and, as farming spread, so did settlements throughout the Salt and Gila river valleys. (The Gila River is less than a mile from the Casa Grande site.) Colonists who shared this culture we call Hohokam moved up the Verde River Valley north of present-day Phoenix, and up the Salt River Valley east of Phoenix. They also moved downstream as far west as Gila Bend. There’s also evidence of new villages and canal systems arising along the Santa Cruz River in the Tucson area.

As their settlements expanded, trade began to flourish. The Hohokam imported turquoise, pottery, piñon nuts, obsidian, and even seashells from the Gulf of California and the Pacific Coast while their ingenious canal systems allowed their farms to produce surplus crops for export. They also traded their finely crafted shell jewelry and distinct “red on buff” pottery.

Evidence points to the compound at Casa Grande Ruins being a crossroads in the trade system. One major route, reconstructed by archaeologists, went from northern Mexico into the Tucson area and from there into the Gila River Valley.

While we don’t know the name of the community or, indeed, whether the community had a name, Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino provided the first written account of the central structure

when he visited the site in 1694 some 250 years after its builders had abandoned it. It was he who dubbed the edifice Casa Grande and it has been so named since that time. Though the structure we see today is little different than it was in the 1940s, it is quite different from the one Father Kino saw in 1694. As more and more was written about the site, by the 1860s and through the 1880s more people began to visit the ruins. The completion of a railroad line twenty miles to the west and a connecting stagecoach route that ran right by the Casa Grande brought even more visitors who had no reservations about hauling pieces away as souvenirs, defacing the walls with graffiti, or simply vandalizing the ruins causing significant changes and raising serious concerns about its preservation.

Massachusetts Senator George F Hoar presented a petition to the U S Senate in 1889 requesting that the government take steps to repair and protect the ruins. In 1892, President Benjamin Harrison set aside one square mile of Arizona Territory surrounding the Casa Grande Ruins making it the first prehistoric and cultural reserve established in the United States.

Although the Casa Grande itself is the central feature, there’s much more to the site than this lone building. First, the two acre compound surrounding the big house is part of a larger group of communities covering an area more than a square mile in size. Though understanding its purpose is necessarily speculative, near the center of the compound there appears to be a ball court that was typical of Hohokam communities. Archaeologists have found over 200 oval-shaped, earthen-sided structures located in large Hohokam villages throughout southern and central Arizona though they seemed to have been gradually abandoned beginning in the 1100s. Their actual purpose and the type of game that might have been contested there remains subject to broad speculation.

These structures and the outlying communities do present some indication of how long the area was settled before the construction of the Casa Grande itself. The best dating methods available indicate that it was built in the 1300s using material for the Casa Grande and the surrounding structures that’s

a mix of the area’s sand, clay, and limestone called caliche. It’s estimated that completion of the Great House required 3,000 tons of caliche. Given the size of this project, the construction had to have been well planned and organized, requiring a significant cooperative effort of many people. Sadly, although it’s only possible to speculate about it, we can assuredly admire it.

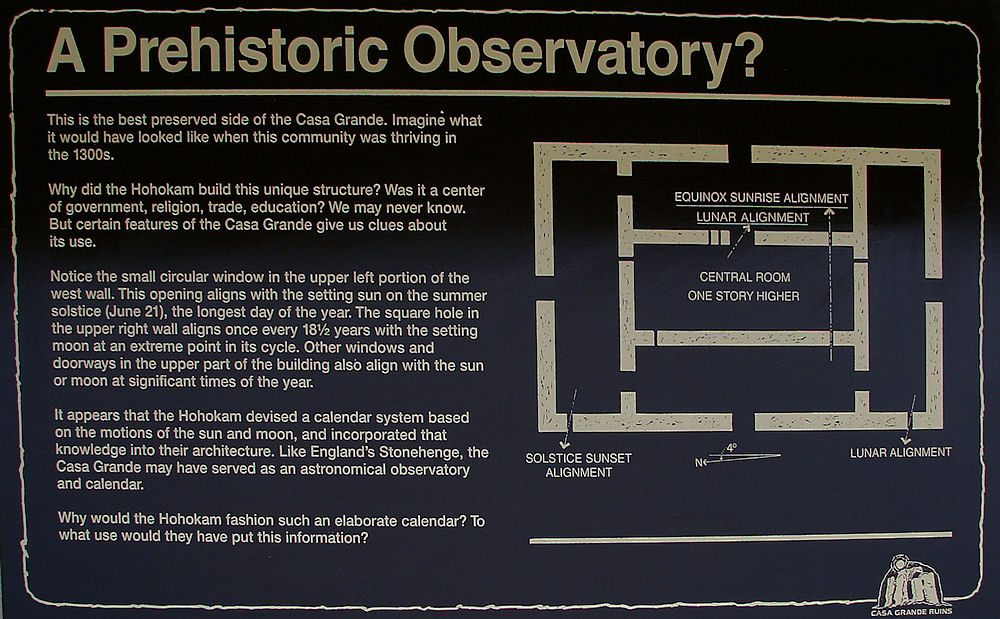

This sign at the site provides one possible explanation.

In truth, it’s unlikely that we will ever know the true purpose of the Casa Grande.