Seeing the Cité.

From the HĂ´tel de Ville it was time to cross one of the 37 Paris bridges that span the Seine. In this instance the Pont d’Arcole.

(Here’s a list of some of the French words and their English equivalents you might see repeated throughout this journal – particularly while we’re visiting Paris:  pont = bridge; passerelle = footbridge or pedestrian bridge; quai = dock or bank; Ă®le = island; rue = street; place = plaza; Rive Gauche = Left Bank; Rive Droite = Right Bank.)

While it might not be the most famous or glamorous of the Paris bridges, the Pont d’Arcole is, in its own right, quite interesting.Â

The original bridge, built in 1828, served mainly as a passerelle connecting what was then called Place de Grève with the Île de la CitĂ© and was originally called Passerelle de Grève or Pont de l’HĂ´tel-de-Ville. In about 1830, it was given its present name. The general assumption is that the name honored NapolĂ©on’s victory at the 1796 Battle of Arcole when he is said to have personally led the charge that defeated the Austrians. There is an alternative theory that a young man who, imitating NapolĂ©on by waving the tricouleur (or Fench flag) as he crossed the bridge, was killed during the “Three Glorious Days” of the July Revolution and who, as he died, shouted, “Remember that I am called Arcole!” As is often the case, the more speculative story is the more interesting story.

In 1854, increased carriage traffic prompted the replacement of the original structure with one better able to withstand those stresses. The new bridge had two innovations. It was the first unsupported bridge across the Seine to be made entirely of wrought iron rather than cast iron. It also had a low, lightly cambered arch. In modern times, the Pont d’Arcole is significant because it was the bridge General LeClerc’s tanks crossed to enter the Place de l’HĂ´tel de Ville in the August 1944 liberation of Paris.

After walking past the Hôtel Dieu (to which this narrative will shortly return) and through the flower market we stopped in front (or perhaps in back) of the Palais de Justice (Palace of Justice) that was in a previous incarnation called the Palais de la Cité.

A Gallo-Roman fortress existed on the site of the present-day palace at least as early as the fourth century and it’s the site where Julian the Apostate was declared Emperor of Rome in the year 360. The palace continued to expand in size and by the sixth century the Merovingian kings used it as their residence when they were in Paris. Recall that Charles the Bald paid a substantial ransom to Viking invaders in 845 to convince them to withdraw from Paris. He then rebuilt and strengthened the walls of the residence and fortress.

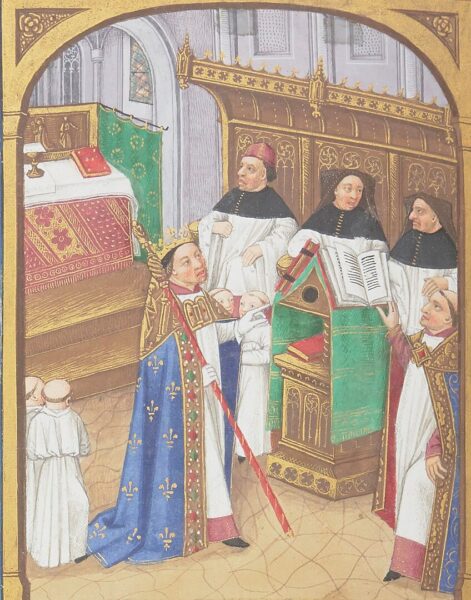

It was under the reign of Robert the Pious that the fortress began to take shape as a palace.

[Image of Robert the Pious from Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

(Robert was the son of Hugh Capet, who had become king in 987 and established the Capetian dynasty that ruled France almost continuously until 1848. Direct descendants of Capet ruled until 1328 followed by branches known as Valois (1329-1589) and Bourbon who ruled until 1792 and again from 1814-1848.) Subsequent kings continued to expand and add on to the palace over the ensuing centuries but it was under the reign of Phillip II who ruled from 1180 to 1223 and who placed the royal archives, the treasury, and courts within Palais de la Cité that Paris truly became the French capital.

In 1187, Phillip hosted the English and Norman king Richard the Lion-Heart thereby demonstrating the new status of the palace and Paris. Records of the time from the royal court show the creation of a new official position, the Concierge, who was responsible for the administration of the lower and mid-level law courts within the Palace. The palace later took its name – the Conciergerie – from this position.

In the middle of the 13th-century, Louis IX, the man who would eventually become Saint Louis, built the long admired Sainte-Chapelle

known today for its stained-glass windows. (I took the photo above on our extended stay in Paris after the cruise.)

During the inaccurately named Hundred Years War (1337-1453) between England and France, Charles V decided to move his residence a safe distance from the center of the city. He built a new residence, the HĂ´tel Saint-Pol, in the Marais district. Later, palaces at the Louvre and the Tuilleries also became royal residences.

While the kings of France didn’t abandon the Palais de la CitĂ© following Charles’ move, its primary purpose shifted to being the center for the administration of the treasury and especially of royal justice. Important prisoners were held at the palace as early as the 14th century. In this way, it wouldn’t be necessary to transfer them for trial from the city’s major prison then at Châtelet.

Although several people important in French history were confined in the palace, for Americans, it’s likely that the most famous prisoner to be held and tried at the Conciergerie is Marie Antoinette. She was transferred to the palace prison on 1 August 1793 where she was held until her execution just more than two months later on 16 October. The area of the Conciergerie where she was held is the section on the right of the photo below.

It’s a HĂ´tel but not a Hotel.

The CathĂ©drale Notre Dame de Paris looms above a square about half a kilometer from the Palace of Justice and adjacent to that square sits the HĂ´tel Dieu. Although the current facility isn’t the original building – in fact its original location was on the opposite side of the island – the HĂ´tel Dieu was established some 500 years before work began on its more famous neighbor.

The Hôtel-Dieu was founded by Saint Landry in 651. It’s considered to be the first hospital in the city and the oldest still operating worldwide. However, hospitals, as we know them today, didn’t exist in the seventh century. It’s more accurate to describe its original purpose as a general institution to serve the poor and sick that offered food and shelter in addition to medical care.

The idea behind institutions like the HĂ´tel Dieu linked piety (which might have inspired the name which translates as “hostel of god” becoming synonymous with hospital) with the idea of providing some measure of assistance and medical care to the poor and thus became an opportunity for many of the bourgeois and nobility to come to their aid. During the Middle Ages, the HĂ´tel Dieu grew in an unplanned and chaotic way and it continued to be a refuge for Parisians until the 17th century. By that time, it had spilled over the river occupying two bridges and a parcel of land on the Rive Gauche.

Building on the notion of assistance and medical care, (and probably also hoping to keep the masses placid) the 17th century elite began to establish a more centralized approach to extreme poverty in France. Under the pretext of fulfilling a religious obligation, they developed a system that was based on the premise that medical care was a right for those without family or income. As part of this effort, they formalized the admission process in hospitals to try to prevent overcrowding and unsanitary conditions.

In truth, things only got worse for the Hôtel Dieu over that span of years. This situation had deteriorated so far that, in 1773 after hearing of its poor patient conditions in which a quarter of those admitted died, often from diseases contracted within its walls, King Louis XV ordered its demolition. However, and perhaps ironically, he died before the order could be executed and his successor, Louis XVI was persuaded to reconstruct rather than raze the damaged parts of the hospital.

In the mid-19th century, the hospital moved to a new, purpose-built home on the other side of the parvis – the location that it occupies today. Following an English model of limiting the size of the wards to about a dozen beds, it finally began to shed its reputation as a disease trap and became a place where people might be treated and even cured.

The HĂ´tel Dieu is still in operation today primarily treating diabetes and endocrine illnesses. According to some hospital literature, it deals almost exclusively with the screening, treatment, and prevention of the complications associated with diabetes mellitus. This is the hospital’s courtyard.

If you’ve been waiting for our visit to Notre Dame, it’s coming in the next entry.