The only sign of Montezuma is the sign.

As I continued my northward drive toward the Grand Canyon, my next stop would be Montezuma Castle National Monument. There’s an old joke that I first saw on a Benny Hill show about what happens when people assume. The joke goes like this:.

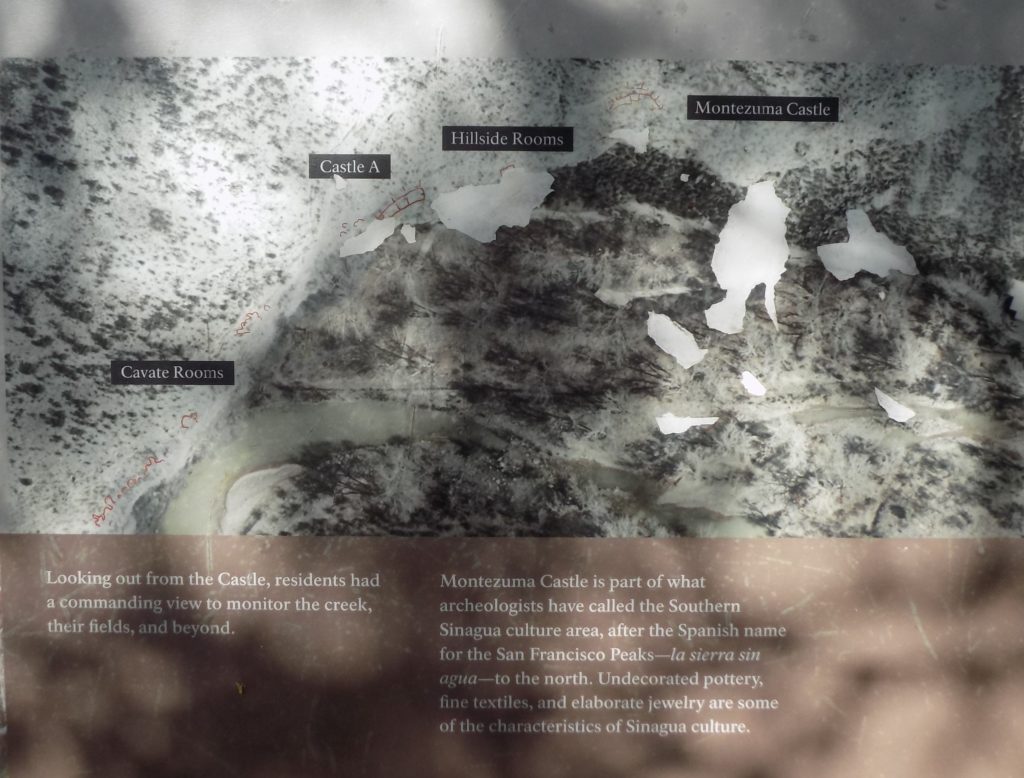

And assuming is just what the early American settlers who came across this five-story 20-room dwelling in a cliff recess sitting 100 feet or so above the Verde Valley floor did. They were so impressed by the structure that they assumed it had to have been built by the Aztecs and named it Montezuma’s Castle. The Hopi who are among the descendants of the ancient people who built it call the place Sakaytaka (“the place where the ladders are going up”) and Wupat’pela (“long high walls”).

Much like Father Kino’s naming of Casa Grande, the colloquial term became part of the lexicon, so Montezuma’s Castle it has remained. Also, like the structures at Casa Grande, we are not likely to learn which ancient people actually built and lived in this complex of cliff dwellings.

Most (if not all) of the available literature attributes the castle’s construction to the Sinagua Indian culture. Although Sinagua creates some distance from Aztec attribution, people familiar with Spanish will recognize that this, too, is not a Native American word but rather as a compound of the Spanish words sin (“without’) and agua (“water”) a term created in the 1930’s by Doctor Harold S Colton – an archaeologist who founded the Northern Arizona Museum. Although scholars remain as uncertain about the origins of this prehistoric people as they do about the people who built Casa Grande, I will call the people Sinagua and the place Montezuma’s Castle because, like Hohokam, they represent commonly accepted usage.

At about the same time the Hohokam built Casa Grande – between 1100 and 1350, the Sinagua constructed and occupied Montezuma’s Castle roughly 150 miles to its north. Somewhat curiously, many archaeologists believe that, despite the apparent risks in its construction, this complex was built by Sinagua women. As at Casa Grande, the 65-room five-story “castle” itself

is the centerpiece of a larger community of dwellings.

A small lake dubbed Montezuma Well lies roughly six miles upstream from the castle’s location and Sinagua farmers diverted its water (making this tribal name a bit ironic) to irrigate their crops.

Biologically, the Verde Valley is an ecotone. This is a transitional area between two more distinct biomes. This mingling of biomes provided more than twenty-five species of plants that the Sinagua used for medicine, dyes, baskets, roofs, and food. Seeds of buckwheat, rice grass, and amaranth, or dried cactus fruit provided the people with several sources of flour. Oils came from sunflower seeds and walnuts as well as nuts from piñon pines and oak trees. The area was fertile enough that they could harvest fruits such as hackberry, cactus, yucca, rose, and grapes throughout the year.

By the eighth century, adapting the irrigation systems of the Hohokam to their south, corn had become their primary crop though they also grew beans and squash. It also appears that the Sinagua were a part of the trading system of which Casa Grande was an essential part.

In another connection with their neighbors to the south, the Sinagua appear to have abandoned the area around Montezuma’s Castle sometime between 1400 and 1450. Here, too, the reason for their departure is unknown – obscured by the mists of time. Fortunately for us, these traces of their vibrant culture and intricate society remain to inspire awe in us all these centuries later.

The final stop for the day.

By the time I finished at Montezuma’s Castle, the afternoon was getting late. I still faced some 150 miles and at least two hours of driving before reaching the Grand Canyon. So, I filled a bottle with water, took a deep breath and started north.

I didn’t notice the time when I arrived at the entrance to the park, but it was well past 17:00. Despite it being early June, I encountered no delays there. I showed the attendant my senior pass (perhaps the best $10 investment I’ve ever made) and driver’s license, got directions to the Yavapi Lodge and cruised into the park.

Entering the park through the south entrance, you drive through a few miles of piñon and juniper forest that looks something like this

and, I have to admit, it surprised me. For some reason, I expected it would look more like this

because a forest seems out of place while, to me, this scene looks a bit more like it attended some sort of canyon prep school. Since I was surprised, I did a little research.

The piñon pine and juniper grow together so frequently that they are typically referred to as a “PJ” forest. The trees average about 10-15 feet in height but can top out between 20-30 feet tall.

The piñon pine produces a nut that has served as food for both human inhabitants of the area as well as animals like the Abert’s squirrel. The junipers are known for their often gnarled and twisted form. Indians used the stringy bark to weave into sleeping mats and other commodities.

The relatively dry conditions on the south rim restrict the size of the trees that grow there creating what is sometimes called a “pygmy forest.” The moisture necessary to sustain this PJ forest arrives in the summer as thunderstorms and in winter as snow. The trees can survive on a limited amount of moisture because they feature modest foliage, thick bark which resists evaporation, have extensive root systems, and grow very slowly.

The south rim is also host to the drought tolerant yucca plant which was one of the most widely used plants by the prehistoric inhabitants of the canyon area. Apparently, the flora of the north rim (which I didn’t research) is quite different.

The forest reaches almost to the rim of the canyon and, as I did when I rode into South Dakota’s Badlands three years ago, I tried to imagine riding through this forest thinking nothing out of the ordinary is in the offing when suddenly the forest ended and I looked ahead and saw this.

Almost certainly my first thought would have been, “Hole-y bleep!”

The photo above was, indeed, one of my first looks at the canyon. It came after I’d picked up my room key and deposited my belongings in my room at Yavapai Lodge which was about a half mile walk to the canyon rim. I stayed along the rim until sunset which, at first, looked like this

and later, like this:

In my next post, I’ll let you accompany me on my long walk along the South Rim Trail and my short walk down the Bright Angel Trail.