On any day in the second half of the 19th century if one were to travel south from Paris 60 kilometers or so to the small town of Barbizon and the nearby Forêt de Fontainebleau, there is some likelihood that they would see an artist sitting at his easel. That artist might be Camille Corot,

[Fontainebleau Forest by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, from Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0.]

Theodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, or later in the century Auguste Renoir or Edouard Manet all painting en plein air. The ancient trees and rugged countryside attracted them to a place where they could elevate landscape painting from mere background to central subject. What these artists, some of whom would go on to establish the Barbizon School, likely didn’t know was that, though in a very different medium, ancient artists, perhaps as long as 15,000 years before them, had worked all around them in this very area.

[Photo from CRNS News.]

It’s not that complicated.

Why in the Vézère Valley in southwestern France can we find what is likely the greatest trove of Paleolithic cave art of perhaps any location on the globe? As Desmond Collins and Lydie Huyghe wrote in the Larousse Encyclopedia of Prehistoric & Ancient Art,

…the richness of glacial age occupation in certain valleys of south-west France is unparalleled elsewhere and these people were the finest artists. In particular the occupation sites of a short stretch of the Vézère valley in the Dordogne département have revealed a series of superimposed culture strata sometimes totalling many feet thick, which have enabled a sequence of culture types to be established.

They speculate that the area may have had an abundance of game which, in turn, may have allowed for a more settled lifestyle and thus more time for creative expression. This might or might not be true but we can be certain that the area had an abundance of caves. This art dates to about 17,000 years BP and the ice that covered much of Europe would have been in retreat so the notion of a habitable valley rich in diversity is not unreasonable.

The most famous cave paintings, of course, are found at Lascaux most of which, including the horses below date to some 15,000 years BP

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons by Pline CC-SA 2.0.\

There’s also the depiction of a fish in Abri-du-Poisson – dated at 25,000 years – one of the oldest such depictions known.

[Heinrich-Wendel-©-The-Wendel-Collection-Neanderthal-Museum-CC-4.0.]

Even the care given the remains of the five humans at a rock shelter near Les Eyzies that gave its name Cro-Magnon as a term to apply to all early modern humans in Europe survives as an indication of early human activity.

Travel northeast toward from Dordogne toward Paris and when you arrive in the area you will find a dearth of caves and less abundant game. As one researcher points out, the Paris Basin not only lacks habitable caves but, “has few karstic cavities that could have been used for highly developed rock art.” And yet, here in the Fontainebleau Forest less than 80 kilometers from Paris, we find rock art.

The art that has been found and studied spans thousands of years and an untold number of creators. There’s significant variation in style, content, and the time in which it was created as each individual expressed their own vision. Whether we discuss the 25,000 year old fish of Abri-du-Poisson or the cave painting of Lascaux and others, the art found in the Vézère Valley dates from the upper Paleolithic to the early Mesolithic periods.

In the case of Fontainebleau, while a definitive answer regarding the initial date of creation remains unsettled partly because of all its multifaceted layers, the oldest art found in Fontainebleau was likely created no more than 6,000 years BP and is usually attributed to the last groups of hunter gatherers who occupied the Paris Basin before the advent of agriculture some 4,500-5000 years ago.

[Human migration map from ScienceDirect Anne Tresset, Jean-Denis Vigne, “Last hunter-gatherers and first farmers of Europe”.]

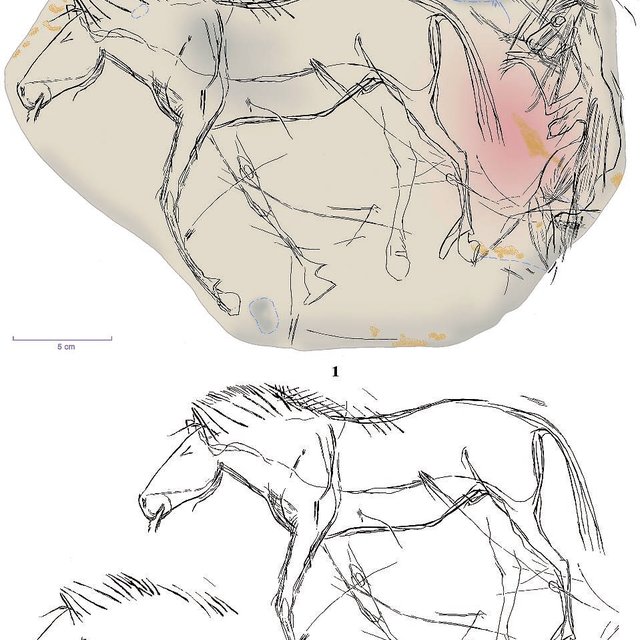

The art itself is characterized by grooved lines and grids etched and chiseled into the soft sandstone walls. There is also a notable absence of animal representations of the sort well established in the Dordogne area. However, although most Fontainebleau art is non-figurative, some figurative engravings have been found such as the finely engraved figure of a horse on a pebble discovered at Ségognole à Noisy-sur-Ecole in Seine-et-Marne.

[Reproduction from ResearchGate by Carole Fritz.]

It is stylistically similar to those in the Dordogne which opens the intriguing possibility that it dates from the Magdalenian Era in the Pleistocene Epoch.

Two techniques typify the engravings in Fontainebleau. Outside shelters and on open-air boulders, the artists used a pecking technique. The majority of the figures inside shelters are grooved. Stylistically, the Neolithic art has several points in common with megaliths in Brittany. These have been dated to the 5th millennium BCE thereby adding some measure of support to the age attributed to the early works found in Fontainebleau.

In addition to a range of motifs, the Fontainebleau art is accumulatively layered. Hundreds, if not thousands, of lines that are superimposed and intertwined cover several square meters of the walls of the densest sites. This suggests not only different graphic intentions but different chronological periods as well. It seems that each subsequent artist who came to a location left their mark with little regard to maintaining a coherent vision attributable to any preceding creator.

A brief digression.

Someone recently asked me why I’ve restricted the award of the scholarship I’m endowing at UMBC to students with a declared major in Visual or Performing Arts. I replied that it bears some relation to my major when I attended but that I also wanted to recognize the importance of the arts in not only reflecting but often shaping the human condition and more specifically our worldview. {Contributions to help me build the endowment and accelerate grants to current recipients are welcome, by the way. Use this link, choose select my designations, scroll to the bottom to select Other, then enter Carton Family Scholarship.}

In researching and drafting this post, I realized that, while true, my answer was also incomplete. The arts and creativity must in some way be essential to our humanity. Whether in the caves at Lascaux or the rocks at Fontainebleau the need for artistic expression seems to have emerged with the genesis of our humanity. If, indeed, the rock art at Fontainebleau spans generations, it cannot help but emphatically point to our very human need to create.

Regardless of where our rapid technological advances take our species, I cannot imagine that this core part of who we are will ever be absent from who we become.