Who were the first humans to populate Fennoscandia and northwest Europe and where did they come from? Believe it or not, until quite recently these questions have been a hotly debated issue among archaeologists that seems to be reaching some resolution in the early 21st century. And those of you who have read even my superficial discussions of human evolution and migration in this series should be able to anticipate the tool that’s making this possible. Of course, that would be the science that allows the decoding and sequencing of the human genome. So, let’s dive into that pool.

Apparently the twain did meet.

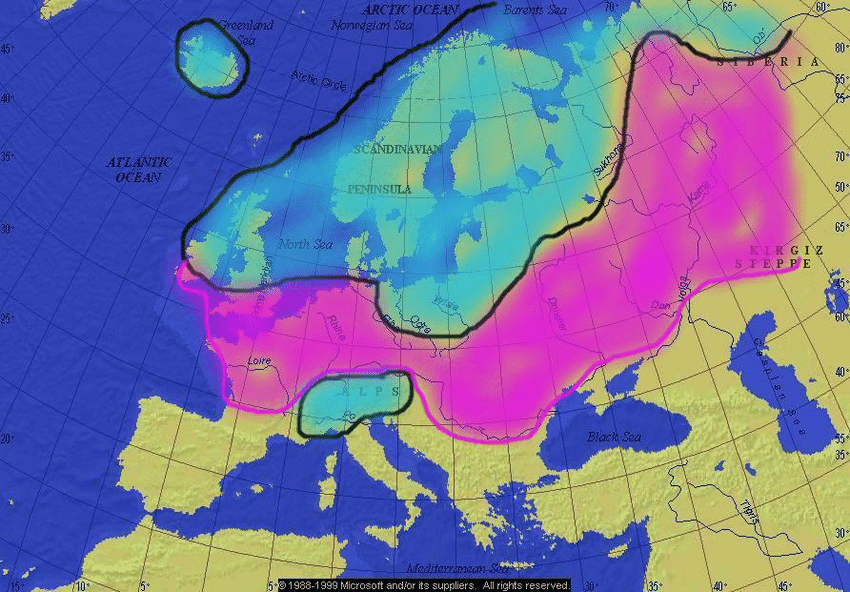

Archaeologists have a high degree of certainty about two aspects of human migration into the Nordic part of Europe. (Note: For brevity, I will refer to this area as Fennoscandia despite it being imprecise.) The first element is that this was the part of the continent humans occupied after the end of the last glacial maximum (LGM) when Europe looked something like this.

[Map from Researchgate].

The ice sheet gradually receded and, as the land became more habitable, different types of flora and fauna reemerged. As they proliferated, human expansion was all but inevitable. The earliest evidence for human habitation on the Scandinavian Peninsula dates to about 11,700 BP.

The second aspect on which there was general agreement was that this migration came from the south and southwest areas of Europe proceeding northward and inhabiting mainly coastal areas which were the first to lose their ice coverage. This not only makes sense geographically but its supported by similarities between late-glacial lithic toolmaking methods in southwestern Europe and Scandinavia – particularly coastal Norway.

Some confusion arose because of stone tools in Arctic Norway that used a flaking technique called pressure blade that differs from the direct blade percussion technique common in the south. In fact the pressure blade method was commonly used in eastern Europe. The attempt to explain this difference had two alternative hypotheses. One is that there was some contact with cultural exchanges between groups in the west and groups from the east. The other is that there was, in fact, a second migration into Fennoscandia originating from the east.

Does DNA-man have the answers?

Once again, those of you who have been reading along know that the advent of DNA sequencing has had a dramatic impact on archaeology and the way archaeologists approach their subject. With DNA sequencing in their toolbox, no longer do they need to rely solely on interpreting tools and artifacts.

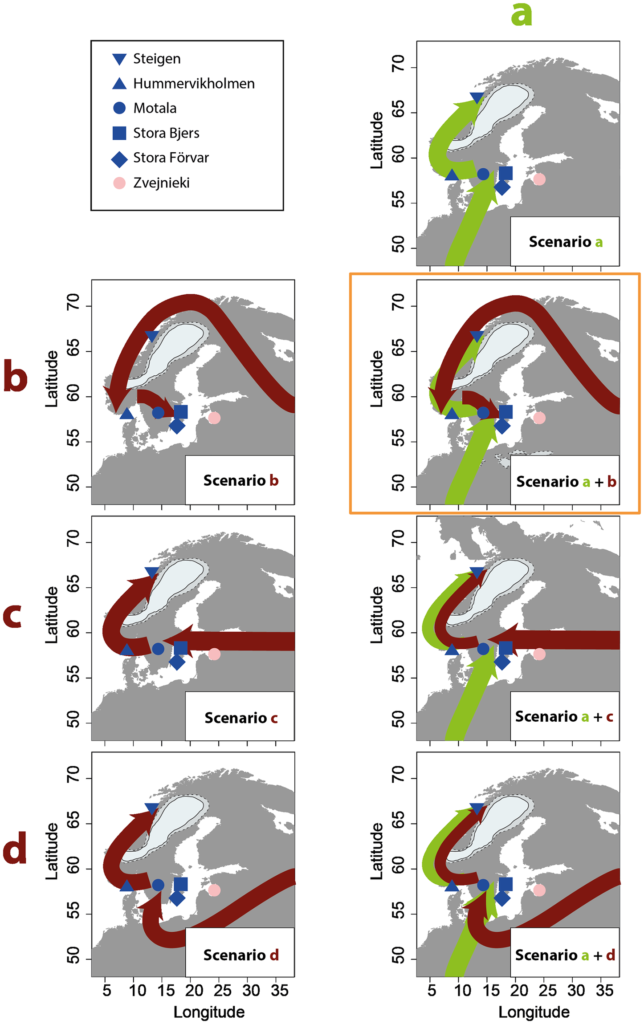

Two distinct source populations emerged from the earliest results of sequencing the DNA of Mesolithic human remains from central and eastern Fennoscandian hunter-gatherers.

[Genetic map from journals.plos.org.]

Unsurprisingly, one source originated in western, central, and southern Europe. However, these intact bones also revealed that there had, indeed, been a migration from northeastern and eastern Europe. The geographic distribution showed that DNA from fossilized bones in northern and western Fennoscandia most closely resembled DNA of people from northeastern Europe. Skeleton fossils from southern and eastern Fennoscandia most closely matched DNA from southwest Europe.

Now, scientists can generally agree that humans took two distinct migratory paths into Fennoscandia. At present, the probable route or routes remains an open question.

[Maps of possible routes from journals.plos.org.]

Another intriguing clue might come from Finland. A joint project between researchers from the Max-Planck-Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of Helsinki analyzed the first ancient DNA from mainland Finland. While not dating to the Neolithic, and certainly far from definitive, scientists extracted DNA from bones and teeth from a 3,500 year-old burial on the Kola Peninsula in Russia, and from a 1,500 year-old water burial in Finland. The results revealed a possible path for ancient people from Siberia to spread to Finland and to Northwestern Russia.

Could Fennoscandia have been the original melting pot? Could it have been a place where people from continental Europe and the Urals came together and shared new technologies from as far away as China such as the manufacture of ceramics? Admittedly, this conclusion is a bit of a leap and it’s far too early to conclude too much yet. But it’s certainly an intriguing possibility.

Blonde hair and blue eyes.

In terms of genetic diversity, the human population of Stone Age Europe has some markers of being more the inverse of present day Europe than its parallel. And, in light of the previous section, this makes some intuitive sense. The mixing of populations in the north created wider genetic variation in its populations than the more homogeneous south. In today’s Europe, we find greater genetic heterogeneity in the south and more homogeneity in the north even as new migrations bring new diversity across the continent.

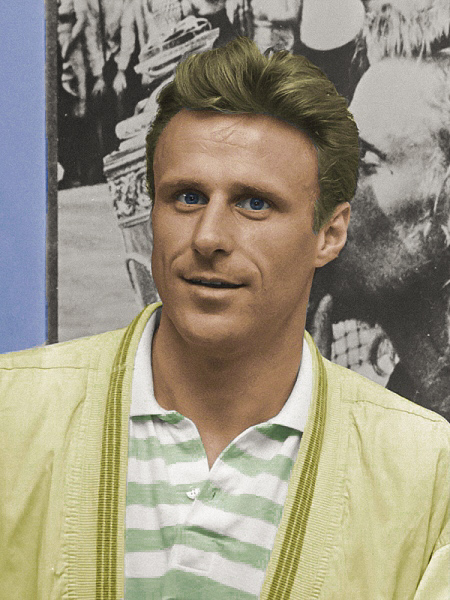

When you picture a typical Fennoscandian you might think of Björn Borg (if you’re old enough)

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons BY Roland Gerrits by CC-SA3.0.]

or maybe someone who looks like Malin Akerman

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons BY David Shankbone by CC-SA3.0.]

Work on the genome has revealed that the people from the south brought blue eyes while people from the northeast brought pale skin. Likely because variants associated with light skin help people better absorb and synthesize vitamin D, they are found in greater frequency among Fennoscandian hunter gatherers than their counterparts from other areas of Europe. Thus, it’s likely that local adaptation to the high-latitude climate and its associated low levels of sunlight took place in Fennoscandia after these ancient groups arrived.

But why?

I can’t speak for anyone else but I know that someone of my constitution will assuredly wonder what motivated these ancient people to migrate into that cold climate and its months of short days and long nights. Frankly, I wonder that today when we have technology that makes those circumstances far more bearable.

Could it have been a desire to escape tribal power struggles? Could the changing climate have filled these northern climes with an abundance of food? Perhaps it was a Neolithic Romeo and Juliet rebelling against their parentally arranged marriages to someone they hated. Or maybe it’s simply because as the image below states,

I’m fairly certain we’ll never know but, as Christopher Prescott of the Norwegian Institute in Rome said, “Traditionally, people have roots. But in recent years, I’ve become more and more convinced that it would be more accurate to say that people have feet.”

A few words about the Sámi.

For much of recent history, the Sámi people have been known as reindeer hunters but this aspect is a more recent development in a culture that has inhabited the northern parts of Europe (Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia – especially Siberia) for around 5,000 years.

In the DNA section above, I mentioned the joint study by researchers from the Max-Planck-Institute for the Science of Human History and the University of Helsinki. The study compared not only the ancient individuals to one another, but also to modern populations, including Sámi, Finnish, and other Uralic language speakers. (Uralic languages are spoken by the majority of the population in Finland, Estonia, and Hungary. Uralic languages are also spoken by minorities in the far northern reaches of Norway, Sweden, and Russia.) The study found that among modern European populations, the Sámi have the largest proportion of this ancient Siberian ancestry.

(Traditional Sámi dwelling taken on my visit to Skansen in Sweden.)

Thiseas Lamnidis, co-first author of the study says of the findings, “Our results show that there was a strong genetic connection between ancient Finnish and ancient Siberian populations suggesting that ancient populations from Siberia may have also shared a subsistence strategy, languages and/or cultural behaviors with Bronze Age and Iron Age Finns, despite the large geographical distance.” This raises the intriguing possibility that ancient Finnish populations lived a mobile, nomadic life, trading and moving over a large geographical area.

Since this is the first exploration of ancient DNA from Finland, it adds to our knowledge of how the ancient people in the area lived while simultaneously raising more questions for researchers to explore.

Next stop, Sarajevo.