From Opening….

For all its success in design and execution, for all the glory of the athletic competition, for all the kindheartedness and generosity of spirit displayed by the Norwegian people, one troubling scene staged a backdrop to these most successful of Winter Olympic Games. It was happening more than 2,000 kilometers to the south in the largely sectarian religious war that had begun years earlier when the death of Josep Broz Tito unraveled the flimsy scrim that had obscured the sham of a unified Yugoslavia – and where Serbian troops continued their siege of Sarajevo, the beleaguered capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina that had hosted the Winter Olympics a decade earlier.

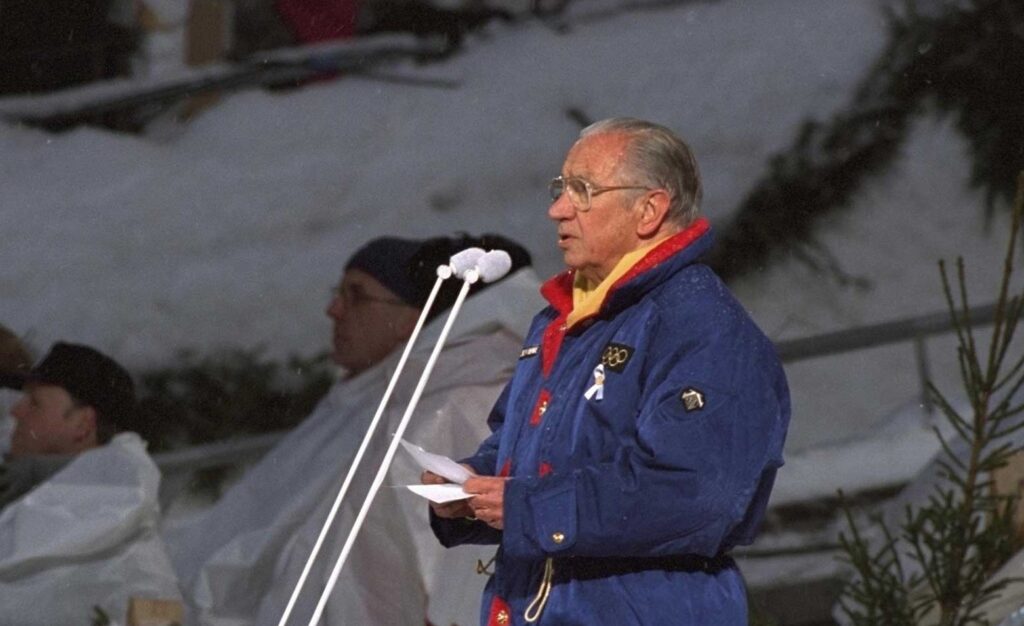

The day of the opening ceremony of the Lillehammer Olympic Games was the 679th day of the Serbian Army’s siege of Sarajevo and, almost incomprehensibly, the citizens of that city had not even passed through half the time they would ultimately endure under siege. Olympic opening ceremonies are always celebratory and anticipatory. The one held at Lysgårdsbakken in Lillehammer was little different until the moment IOC President Juan Antonio Samaranch reached the podium with the same task he’d had almost precisely a decade earlier in the now besieged city.

[Photo from Olympics.com].

More than 40,000 people listened as Samaranch, the white peace ribbon clearly evident on his blue parka, briefly stepped outside his role as promoter-in-chief. “Please stop the fighting, stop the killing,” he said in an impassioned tone. “Drop your guns, please.” He then asked everyone in attendance and those watching on television to stand for a moment of silence in memory of the victims on both sides of the strife in Sarajevo. The gesture may seem small and insignificant but it was undoubtedly a difficult step for a cautious man particularly coming barely a week after a deadly mortar attack on the Markale open air market in Sarajevo that killed 68 people and wounded another 144. It certainly set a more somber tone for the Games to come than the usual President’s speech.

Bonnie Blair said she thought about the siege during those weeks in Lillehammer. She said she wondered about the family who’d hosted her own family in Sarajevo. Was that family still there? Was that family even alive? “It really was sad to know that they were using the 1984 ski jump as a missile launch. And that our rink was now a graveyard.” (So many people died in Sarajevo that the Olympic Zetra Ice Rink had to be used as a morgue.)

The spirit of sport.

Through all the strife and disruption in the young nation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, through circumstances that led to a news conference where the president of the country’s Olympic Committee called Sarajevo “the largest concentration camp in the world,” they nevertheless sent a 10 person team to Lillehammer. That team was:

Enis Bećirbegović – Alpine Skiing.

Arijana Boras – Alpine Skiing.

Bekim Babić – Cross Country Skiing.

Nedžad Lomigora – Men’s Luge.

Verona Marjanović – Women’s Luge.

Zdravko Stojnić – 2 Man Bobsleigh w/ Zoran Sokolović.

4 Man Bobsleigh – Zoran Sokolović; Izet Haračić; Nizar Zaćiragić; Igor Boras.

[Photo from Olympics.com].

Boras, arrived in Oslo via a United Nations flight on the day of the Markale massacre and was walking through the terminal when he saw it reported on Norwegian television. He knew that had he not been on that flight he might have been among the dead or wounded because he lived in a Catholic seminary only 100 meters from the market. When he reached the Olympic Village he later told reporters, “I couldn’t stop crying. Life is so cheap now, not worth the price of one bullet.” With heavy hearts and conflicting emotions, the Bosnian athletes went on.

As they entered the stadium behind their country’s flag, the CBS announcer noted that most likely the bobsledders, who were all from Sarajevo and who had risked their lives simply getting out, would be sent to refugee camps.

The day after the Opening Ceremony, when asked about his feelings, Zaćiragić told an ESPN reporter that yes, he had enjoyed the ceremony adding,

But yesterday, every single athlete was so empty. It was awful. I felt so terrible. It was the worst feeling I have ever had. I felt, ‘Should I be here? Is this right?’ I thought of all the people suffering back home. They have nothing. No heat. No clothing. No food. I am here to help our battle against the fascists, but should I be here?

I notice everything here, but I can’t feel it. I was a young man before the war. I used to chase girls. I used to have fun. Now I just spend my time sitting in my room writing.

But still he competed.

Verona Marjanović, the daughter of a Serbian father and Croatian mother who would compete in the women’s luge said,

I’m ashamed to be here. I left all these people and they are getting killed, and I’m here just to do sports. If you live in Sarajevo, you don’t know what it is to be free. If you’re not in Sarajevo, you don’t have to worry about food, you don’t have to worry about getting killed while you sleep, you don’t have to worry about drinking a cup of coffee in a café.

But still she competed.

There would be no medals for any of the Bosnian athletes. Had the USA 2 sled not been disqualified, the Bosnian four man bobsleigh team would have finished last. The team had a noteworthy makeup, though. It was comprised of two Muslims, a Croat, and a Serb. Igor Boras told reporters, “In our small bobsled, we try to symbolize our country and show the world that we can and we must live together.” (This very much reflects the sentiments expressed by the people I met on my 2016 visit to Sarajevo – a visit I’ll recap in a later post in this series.)

….to Closing.

Anthony (Tony) Maglica was born in New York City but grew up on the Croatian island of Zlarin. Maglica’s Croatian mother had returned to her homeland during the Great Depression and the family had to remain in Croatia throughout World War II.

They returned to the United States in 1950. Tony was 20. Living in Ontario, California, Tony established a business in his garage that he named Mag Instrument. He invented a flashlight he called Maglite that earned him hundreds of millions of dollars.

Although he was Croatian, when the war began in Bosnia, he hurriedly shipped 50,000 of his company’s six-inch black flashlights to aid people with no electricity. In 1994, he sent 40,000 special Maglites to Lillehammer.

The plan was to use them at the end of the Closing Ceremony during a moment of silence where they would serve as gestures of hope, candles of peace.

Years later, Blair recalled that Closing Ceremony, “They asked for a moment of silence for Sarajevo. We all stood and waved thin, black flashlights that had been labeled ‘Remember Sarajevo.’ I still have mine.”

[Photo from Popsugar.]

And beyond.

One American who was watching that opening ceremony paid close attention when the announcer talked about the Bosnians returning to refugee camps and “wondered if there was something I could do.” Her name is Susan Osterberg. She was 30 years old and living in Washington, DC where she was the manager of Applied Communications.

It was a slightly more innocent time but the next day when Osterberg phoned CBS in Lillehammer, she spoke to a producer who knew Boras and connected the two. She asked Boras how she might help the team avoid being sent to refugee camps. Boars asked if it was possible for them to come to America.

Osterberg began working the phones calling immigration lawyers and trying to find an organization who would sponsor the team. Having been rejected by three universities, Osterberg finally spoke with Professor Joshua Goldstein, American University’s chairman of its Bosnia Support Committee. Goldstein then persuaded A U officials to give the team the “Keeper of the Flame” award and sponsor their visit. The U S State Department could now set the wheels in motion.

After Osterberg agreed to pay for two airfares and Tony Maglica the remaining four, the five bobsledders and their alternate Alan Durmic flew to America after the closing ceremony. At the invitation of A U’s president, Elliott Millstein, they were able to stay at least through the academic semester. In a June 1994 story about Osterberg and the Bosnians, the Washington Post wrote,

The six won the award because they are examples of what Sarajevo once was and needs to be again: a city of tolerance and tranquility. The bobsledders — three Muslims, two Eastern Orthodox and one Catholic — represent the diversity that long prevailed: Haracic is a Muslim married to a Croatian; Stojnic is a Serb married to a Muslim. If the Bosnian bobsled team had ethnic or religious restrictions placed on it — which is how those who are calling for a partitioning of Bosnia want the country to be shaped — these athletes couldn’t have come together to race in Lillehammer.