Today I’ll begin with a one question quiz: When you think of the greatest Impressionist painters, who is the first painter that comes to mind? Have your answer? Good.

Now I’m going to provide a list of seven painters and predict that your answer is one of the painters on the list. Alphabetically (by surname) the painters are: Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, or Alfred Sisley. If some among you thought of Van Gogh or Matisse or even Mary Cassatt, I think you’d find yourselves in the minority.

If you follow this link to a Wikipedia Category page, you’ll find a list of 36 subcategories including one for French Impressionist Painters that has eight subcategories and 48 painters alone. So, why these seven and not any of the others?

All seven of the painters on my list have something in common and it’s not simply that they are all, with the exception of Sisley who was English but lived most of his life in France, French. What they have in common is another painter – perhaps equally great – whose name you should know but possibly may not. That man is Gustave Caillebotte. This painting, called The Floor Scrapers, is one of his most important.

I’ll return to Caillebotte and the seven Impressionist painters anon but first, join me this morning as our group visits the Musée d’Orsay said to have the largest collection of Impressionist art in the world.

Once a train station, not always a train station.

We set out from the hotel in three buses (I refuse to call them coaches as the travel and bus industries do. To me, coach sounds much more elegant and comfortable than this mode of transportation tends to be. “Your coach awaits, milady.” I think not!) toward the utter chaos that is the Place Charles de Gaulle formerly known as the Place de l’Étoile. This traffic circle with the Arc de Triomphe in the center sits at the western end of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées although that is only one of a dozen streets that converge on it. It’s so large that it has two street names. The Northern half of the circle is called Rue de Tislitt and the southern arc is the Rue de Presbourg. It’s so large that it occupies space in three different arrondissments – the 8th, the 16th, and the 17th.

I somehow recall of one of our guides telling us that in traffic circles in France the vehicles in the roundabout always have the right of way – except in Place Charles de Gaulle when that right is given the vehicles approaching from the right as this video seems to confirm.

We navigated the Place successfully and without incident, crossed the Seine on the Pont de la Concorde to the Rive Gauche and proceeded to our appointed stop at the Musée d’Orsay (hereafter the key stroke saving Orsay). But first, a bit of history.

One side of the 173-meter-long building that is now the Orsay faces the Seine along the Quai Anatole France. The other side runs along the Rue de Lille which, until the death of Marguerite de Valois in 1615, served as the central avenue in the personal garden her husband King Henri IV (the first of the Bourbon kings) had built for her. François Ravaillac had assassinated Henri some five years earlier and, after his mother’s death, Louis XIII, Henri’s successor, started selling the garden in parcels. Private aristocratic mansions began being built in the neighborhood and this mainly residential construction continued for nearly two centuries.

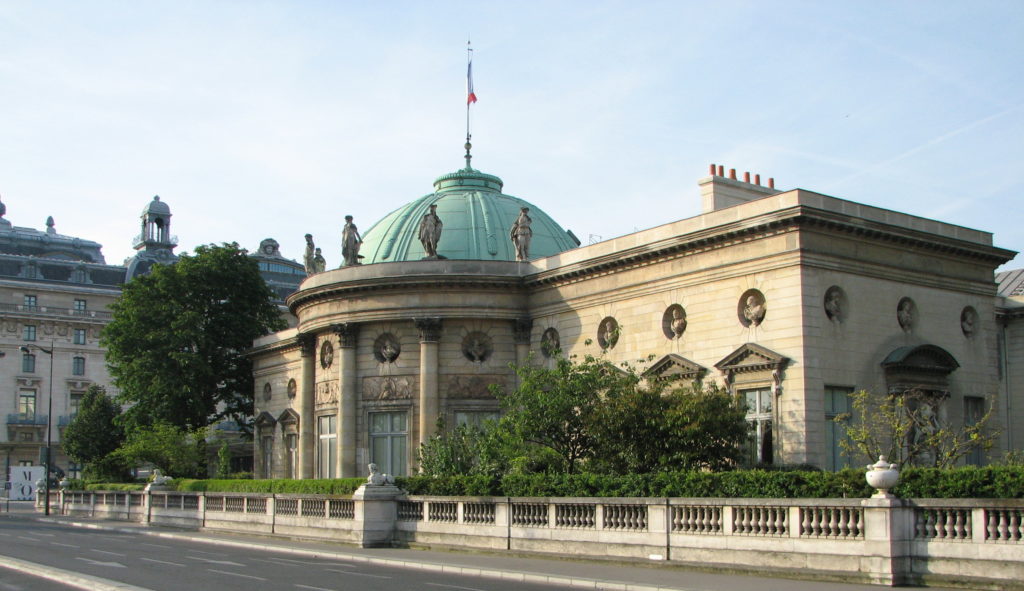

One of the more famous buildings was the Hôtel de Salm built between 1782 and 1787 as a residence for the German prince Frederick III, Prince of Salm-Kyrburg. The building was a favorite of Thomas Jefferson, America’s Minister to France from 1784-1789 who based his design for his home at Monticello on it.

Between 1810 and 1838, two buildings came to occupy the current site – the Cavalry barracks and the Palais d’Orsay. The latter was originally intended to serve as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs but instead came to be used for Cour des Comptes (Court of Accounts) and the Conseil d’État (State Council).

Riots and battles engulfed Paris during what is known as “Bloody Week” which overthrew the Paris Commune in May 1871 (and that I discussed briefly in this post). The Hôtel de Ville was not the only building to burn during that week. Nearly all the buildings in this neighborhood – including the Palais d’Orsay – burned as well. The French left the burned ruins in place for nearly three decades to serve as a reminder of that civil war. However, unlike the Palais d’Orsay, the Hôtel de Salm was rebuilt and serves today as the Palais de la Légion d’Honneur (Palace of the Legion of Honor).

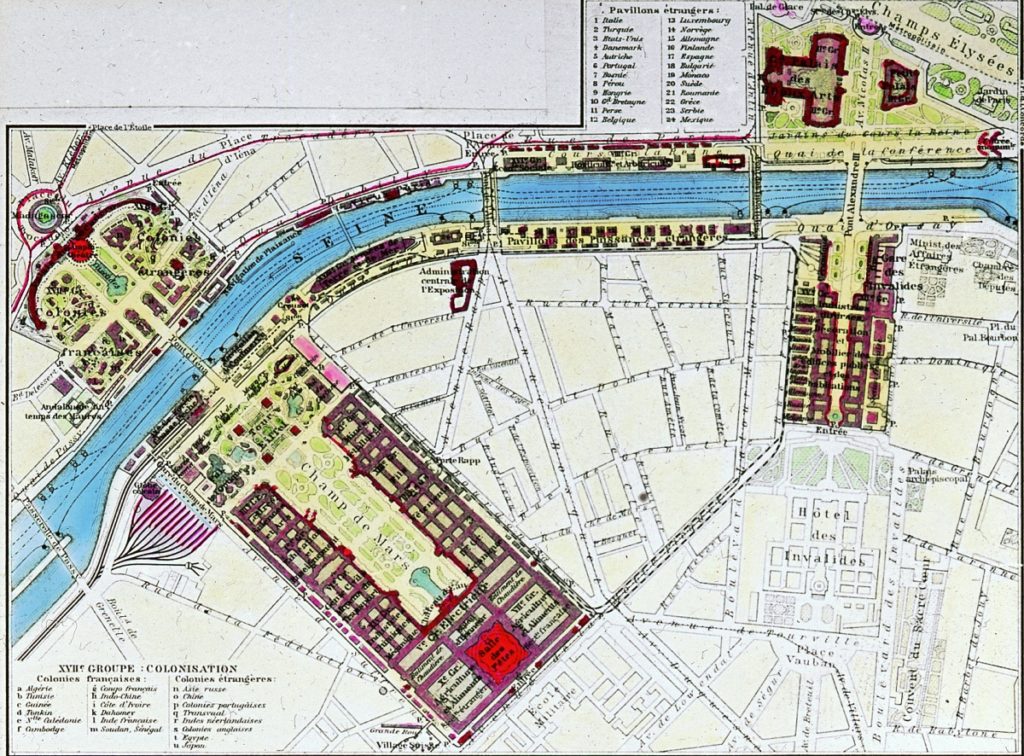

Within about two years after hosting the Exposition for which the Eiffel Tower was built, the French Republic announced plans for a new World’s Fair that would welcome and celebrate the coming of a new century. The site of the fair would be the Champs de Mars.

The main train station at that time – the Gare d’Austerlitz – was operated by the Orleans Railway Company and was the closest station on the Rive Gauche to the proposed site of the Fair but it was some six kilometers distant.

Feeling itself disadvantaged by the remote location, the company convinced the government to cede the land for a new station on the site of the Palais d’Orsay. They designed the new station to integrate aesthetically with the surrounding buildings that included the Louvre on the Rive Droite and the Palais de la Légion d’Honneur next door.

Completed within two years, the Beaux-Arts Gare d’Orsay, which included a 370 room hotel

opened during the middle of the exposition on 14 July 1900 and it served as the main terminus of the southwestern French railroad network until 1939. However, from that year forward the station could serve only the Parisian suburbs with a handful of trains because its platforms had become too short to accommodate modern, longer trains.

Although the station was essentially out of operation – though it did serve as a mail center for packages sent to soldiers during World War II – the hotel managed to stay in business until 1973 when it, too, finally closed.

By 1975, two opposing plans were being formulated to determine the building’s fate. One would have razed the Gare d’Orsay and replaced it with a modern hotel complex. The other, suggested by the Direction des Musées de France proposed installing a new museum there. Abetted by a renewed interest in 19th-century architecture, the latter plan emerged victorious and by 1978 the building had been declared a national monument.

The exterior was restored but with an eye to respecting the original construction and the vision of the building’s original architect, Victor Laloux. The real key would be the design of the interior space. Perhaps in a bit of a surprising decision, that challenge was awarded not only to an Italian architect but to a woman, Gae Aulenti.

Aulenti decided to highlight the great hall and utilize it as the main artery of the museum with different galleries accessible from the skylit atrium. At floor level it looks like this:.

or this from an upper level looking down like this.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

Very interesting, especially the rise of impressionism and the 7…

Their traffic patterns look like utter chaos…I’d have to have a cooler filled with alcohol at all times if I had to drive there…

Would like to hear more about the food when you were in country (not the ship, been there, done that). Maybe some of the dishes and wine you sampled..What you did and did not enjoy…

I’ll have a little more about the food when I return to Paris later in the trip but did very little dining off the ship at this point. It’s mostly a few lunches – one in Arromanches and one in Bayeux come quickly to mind – that I’ll probably mention in passing when they arise. You’ll get almost nothing about wine. I drink beer and beer is basically an afterthought all over France.