A visit to Johnston Canyon.

Named for a prospector who discovered gold there some time prior to 1910, Johnston Canyon is neither remote nor off the beaten path but it presents a different aspect than the lakes and mountains of Banff. The 2,500 meter walk to the upper falls is among the most popular hikes in the park. Although it wasn’t particularly pleasant on my sore ankle, with an elevation change of between 135 and 150 meters it wasn’t particularly strenuous.

Johnston Creek – a Bow River tributary – is primarily responsible for carving through the limestone rock that lines the sides of Johnston Canyon but it was a landslide that prompted its inception. Rivers naturally seek a base line elevation – the point at which it reaches the elevation of the larger body of water into which it will drain. Because the river wants to drain as efficiently as possible, the larger the difference in height between the river and its inlet into, say, another river or a lake, the more energy the river expends in the process of erosion. The more energy it expends, the more rock it carves through and the more rock it carves through the speedier its drop in elevation.

This was the case with Johnston Creek. When landslides blocked its initial pathways, they forced the flow to find new channels. Like most of the canyons in Banff, Johnston Canyon is relatively young with an age of merely a few tens of thousands of years.

The trail to the two sets of falls (Lower and Upper) is paved most of the way and is almost always within either eye shot or earshot of Johnston Creek. However, it’s also narrow and barely wide enough in most places to allow the passage of upward and downward travelers without one or the other turning to the side.

The falls themselves are lovely though not particularly dramatic in either flow, volume, or height. On the other hand, opening yourself to the walk through the forest and along the river can be a reward in and of itself.

For the best, most serene views of the falls, I’d suggest arriving before 10:00 or after 15:00. You access views of the falls by following spurs off the main trail and during midday, you’ll encounter long queues at both. For those healthier and more adventurous than I was on my sore ankle, you should consider walking the additional three kilometers (plus 200 meters in elevation gain) to the Johnston Valley and the aquamarine pools called the Ink Pots.

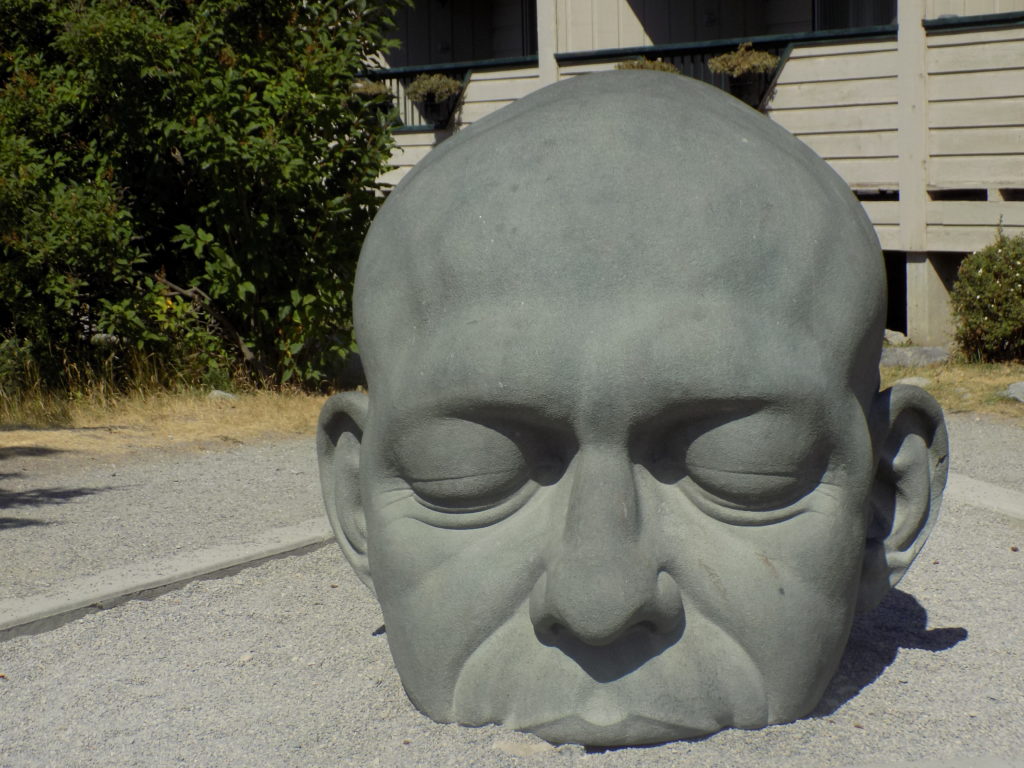

No need to get a big head about it.

By the time I finished my hobble through Johnston Canyon, I’d worked up a bit of an appetite. The town of Canmore is about 30 kilometers east of the park and I’d planned on making at least a brief stop there on my way from Calgary. Since the auto rental delay had forced me to change those plans, I decided to pop out to Canmore for lunch.

I had put this small town on my list of places to see because of this.

The whimsy of the work induced my visit. Since I suspect few of my readers have proficiency in Gaelic, let me explain. The town itself was named for a village in northwest Scotland called Ceannmore named after King Malcolm III who ruled Scotland from 1057-1093 and who was also called Malcolm Canmore.

The whimsy comes from the Gaelic phrase ceann mór that translates as “big head.” This particular big head rising out of the ground is the creation of Alberta artist Alan Henderson. He carved the nine-ton statue from blue granite and, although I only saw him with closed eyes rising contemplatively from the ground, I’d read that from time to time the community accommodates his preference for pirate wear in the summer and a more practical warm cap in winter.

Cave and Basin.

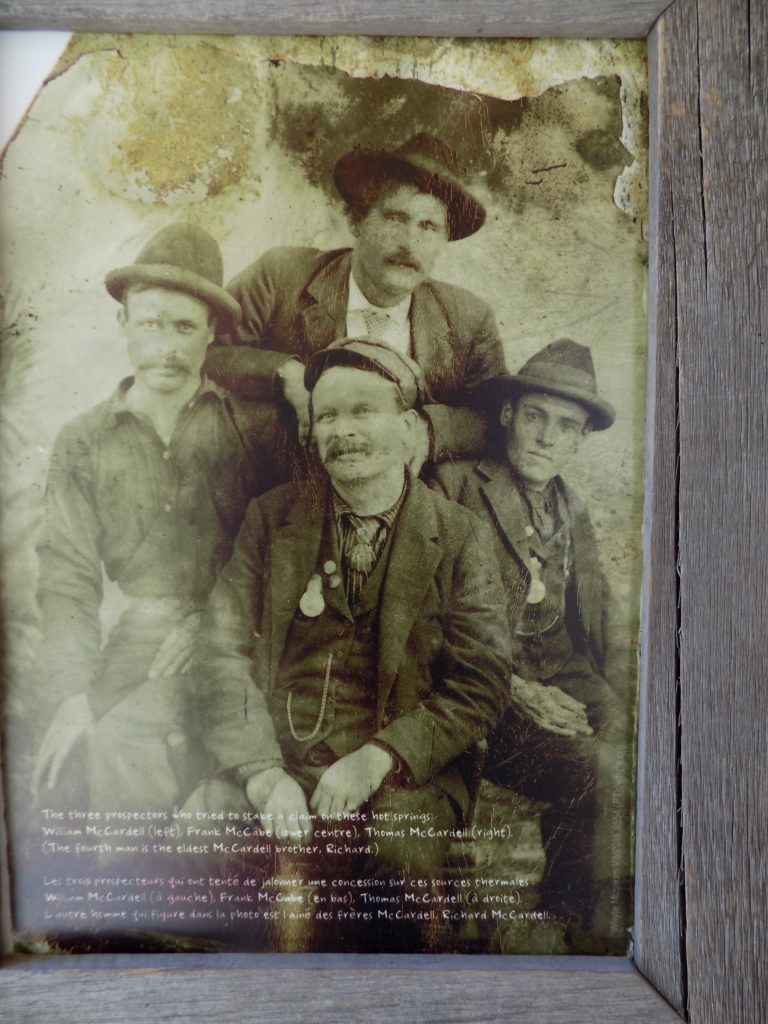

After my lunch in Canmore, (which included an Okangan Spring Honey Kolsch that was a bit too hops bitter for my preference) I returned to the park to visit the Cave and Basin National Monument in the town of Banff. Now it’s time to recall the three CPR workers, the brothers William and Thomas McCardell and Frank McCabe, who were out prospecting when they happened upon a warm stream, followed it uphill where they saw a pool blocked by a tumble of logs, and nearby, a hole in the ground emanating a strong odor of sulfur.

William carved a tree trunk ladder and descended into the hole where he discovered another pool and a spring welling up from the ground. McCardell disrobed and likely became the first European to bathe in the spring. (James Hector, a member of the Palliser Expedition made the first recorded reference to the site in 1859 and a prospector named Joe Healy did the same in 1874 or 1875.)

In a place and at a time when hot water was a rarity, the three men sensed a commercial opportunity. They submitted a claim to the land but since it was neither a traditional mine nor an agricultural site, the government didn’t know how to approve their claim.

Soon five other men tried to stake claims to the site. The Canadian government ended the dispute by claiming the site for itself in 1885, paying a settlement to the McCardells and McCabe, and setting aside those 26 square kilometers that eventually grew to become Banff National Park.

Soon after taking possession of the site, in 1887, the government blasted a tunnel into the Cave and Basin to facilitate entry to the grotto and built a bathhouse. By 1914, they had added a naturally heated outdoor swimming pool that remained in use for eight decades.

The pool no longer exists and visitors to the site today, who are still greeted by an intense sulfuric odor, can walk around the cave but aren’t allowed access to the pool itself. Human intervention over the decades denuded the cave of many of its delicate formations. The introduction of nonnative species – such as the western mosquito fish in 1924 – has led to significant habitat destruction.

Access to bathing in the spring appears to have closed permanently in 1992 and in 2000, Canada placed the Banff Springs snail – first identified in 1926 and which resides exclusively in the various Banff Springs – on the endangered species list. Thus the only permissible human contact with the water is in a small fountain outside the Cave and Basin Building.

Prisoners – but not of love.

Those who are willing to walk a few steps beyond that building, might be surprised to find this small one –

detailing Banff’s World War I internment camp. At the main camp, located at Castle Mountain, the prisoners generally lived in tents. Conditions there were considered exceptionally harsh and they moved to Cave and Basin during winter. Unlike the site I visited in Salina earlier in the summer, this wasn’t a site that housed enemy combatants but rather, men the government viewed as enemy aliens.

Nearly 60 percent (or 5,000 men) of this camp’s population was Ukrainian and it’s sometimes called the Ukrainian Camp. However, its population of 8,759 also included about 2,000 Germans. There were immigrants from other parts of eastern and central Europe and a handful of Turks. The men worked six days a week building much of the park’s early infrastructure and road construction.

Although internment camps were once again set up in Banff during World War II, Canada didn’t reopen the sites at Castle Mountain or Cave and Basin. Megan Hjorleifson of Parks Canada sent this email in response to my inquiry:

“The internment camp barracks were not re-used in the S W W in fact, most were removed by 1922. A part of one may have been used by the Banff Curling Club for a while. Some of the SWW structures from the P O W camps in Kananaskis were re-used as parts of the youth hostels on the Parkway.”

(Kananaskis is a mountainous area between Banff and Calgary.)

There were saw camps at Lake Louise, Stoney Creek, and Healy Creek in the Second World War whose populations were largely composed of Mennonites from Saskatchewan. Internment camps for people of Japanese descent were not sited in Banff during World War II. Rather, these were located in Jasper National Park where detainees worked on the Yellowhead Highway and other projects.

This brings to an end a rather busy day. I’m off to spend the night at the Hotel Blackfoot in Calgary where, together with my “Garlic Shrimp with Angel Hair Pasta” dinner, I’ll discover that Big Rock Brewery’s Grasshopper Honey Lager will have a less foamy head but even hoppier bite than did their Kristalweizen.

Tomorrow I set off for a night in Billings, Montana and if you join me along the way you’ll learn about glacial erratics, a Canadian town that found an interesting way to benefit from its name, and a very short river.