Before we reach the Pinkas Synagogue and the adjacent Old Jewish Cemetery – two of the most important stops on any tour of Josefov whether guided or solo – I need to complete the story of the Quarter that, in the previous post, ended on its eve of destruction.

1893 Acts 22 and 23.

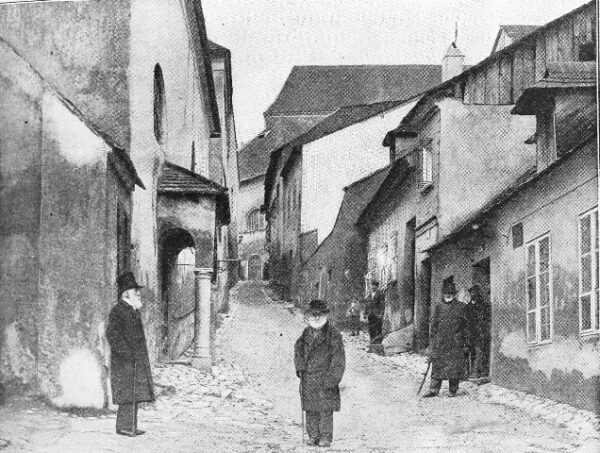

By 1867 Jews in Austro-Hungary were fully emancipated and other edicts in the decade prior allowed them to move out of the Quarter. As more Jews moved out, the Quarter became a little less Jewish and a little more a refuge for Prague’s poor. It wasn’t uncommon to find a two-room flat occupied by 3 or more families. Hygienic conditions began to border on catastrophic and diseases and crime spread nearly unchecked.

EPSON scanner image.

[Image of Old Jewish Quarter from spotlight.anumuseum.org.il].

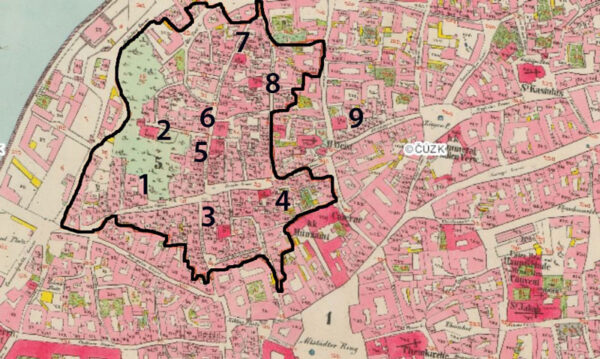

Thus was the situation in 1893 when the government enacted Acts 22 and 23, otherwise known as the Sanitation Laws, that provided the legal basis and financial framework permitting the designation and acquisition of specific redevelopment areas. The city identified 380,000 square meters as Remediation Districts to be targeted for redevelopment. At 92,984 square meters, Josefov accounted for a bit less than 25 percent – an amount that seems not unreasonable given the described conditions.

Work on Josefov began with the acquisition of 260 officially identified residential buildings that would be razed. (The city demolished more than the official number of buildings because many of the buildings in the Quarter were so-called “Black” buildings. These were buildings constructed without permission and that were untaxed, unrecorded on official maps, and uninsured. These types of buildings would have gone unreported in the official count.) Three synagogues would also ultimately face the wrecking ball – the New Synagogue, the Great Court Synagogue, and the Gypsy Synagogue where Franz Kafka had his Bar Mitzvah. When all was said and done, only six buildings survived.

[Map of Old Jewish Quarter from LivingPrague].

The synagogues are:

- Pinkas Synagogue.

- Klausen Synagogue.

- Maisel Synagogue.

- New Synagogue.

- High Synagogue.

- Old/New Synagogue.

- Great Court Synagogue.

- Gypsy Synagogue.

- Spanish Synagogue.

(The Spanish Synagogue for Sephardic Jews was in Josefov but outside the original Jewish Quarter.)

It’s possible that those synagogues that survived demolition did so because the Prague Monuments Commission of Inventory, was established to identify buildings of an historic or artistic nature that could be lost. The Jewish Quarter we walk through today in no way resembles the Jewish Quarter of the late 19th and early 20th centuries let alone that of the 15th century. Although there’s some historical loss, overall, I think we and the residents should be grateful.

From prosperity to slaughter.

The nation of Czechoslovakia came into existence in 1918 at the end of World War I and its foundation received strong support from Jewish organizations. The interwar period not only saw Jews contributing across the economy – particularly in the textile, clothing, shoe, and food industries – but also in the government. Members of Židovská Strana (Jewish Party) gained two parliamentary seats in the elections of 1929 and 1935 and four Jews held ministerial positions within the government during those years.

Then came the Munich Agreement in 1938 and the German annexation and establishment of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia in March 1939. In late 1941 the Nazis established the Terezín ghetto (Theresienstadt) that became a concentration camp for Jews in the Protectorate and for some elderly and prominent Jews from Austria and Germany as well. From that time through March 1945 more than 45,000 Jews were deported from Prague – mainly to Terezín but also to other concentration and extermination camps. It’s estimated that more than 40,000 of them died. In total, more than 80,000 Czechoslovak Jews died in the Holocaust.

Today, the Pinkas Synagogue

is part of the Jewish Museum in Prague. The date of the building’s original construction is unknown but it has a written reference as early as 1492. It became a synagogue in 1535 and was given its name in the late 16th century. After falling into disrepair it was restored in the early 1950s. In the period between 1955 and 1960 it became the main memorial to Czechoslovak Holocaust victims.

Drawing information from card indexes based on transport records, two painters Jiri John and Vaclav Bostik, decorated the walls with names of Jewish World War II victims. The names of deportees from Prague are painted on the walls of the main nave with victims from other towns and communities in Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia inscribed on the other walls of the synagogue.

The original memorial was open for a mere eight years before the Soviet led invasion forced its closure in 1968. After the 1989 Velvet Revolution, the building reopened in 1992 but the walls needed repainting and that wasn’t completed until 1996. It closed again in 2002 after severe flooding prompted another decade of restoration efforts.

(As I looked at this daunting list, the thought that it’s the winners who write history came almost unbidden to me. A Nazi victory in the Second World War would have assuredly turned the mood from somber to celebratory. One person’s benefactor is another’s oppressor. One person’s terrorist is someone else’s freedom fighter. One side’s slaughtered enemy becomes the other’s idealized martyr. And the Butcher of Prague becomes a hero of the Reich)

The Old Jewish Cemetery.

The Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague isn’t the oldest Jewish burial site in that city. That honor would belong to what was once known as the Jewish Garden in Nové Město (New Town) but that was forcibly closed by Vladislav II after demands from the local citizenry. It is, however, the oldest existing Jewish cemetery in Prague and among the oldest surviving Jewish burial grounds in the world. It’s consistently cited as a must see space in Prague.

As you can see from this satellite view from satellites.pro,

the cemetery itself isn’t large and part of it was lost to the construction of the Museum of Decorative Arts during the razing and rebuilding period of the Sanitation Laws. (For some perspective, the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna is nearly 100 times larger.) However, it holds nearly 12,000 tombstones jammed at odd angles like so,

or like so,

and an estimated 100,000 people are buried here. (Graves were often stacked because of the restricted space but also because Jewish tradition – like many other funerary rituals – prohibits Jews from abolishing old graves. Since the community was barred from acquiring more acreage, they opted to add layers of new earth laying it atop collapsed or otherwise eroded tombstones until there were up to 12 layers in a single spot.)

The earliest known grave belongs to the poet Avigdor Kara who died in 1439 and the last known burial took place in 1789. A decree by Emperor Josef in 1784 prohibited burials inside the city wall so subsequent burials took place in a cemetery in Žižkov. (The Old Jewish Cemetery was the second of the three Prague cemeteries I wanted to visit. I didn’t have time to visit the third – Olšany.)

A bit of a lunch adventure.

This ended our time with Jana and we would have a free-ish afternoon before our farewell dinner and final concert. I call the afternoon free-ish because many in the group opted out of taking the tour of the Estates Theater. (I considered using the afternoon for other activities but chose to go on this tour for reasons I’ll detail in the next post.)

Andrea, Bethy, Ross, and I decided to look for a place to have some lunch. The maître d’ at our first choice, a nearby Belgian style restaurant called Les Moules, insisted rather rudely that he had no place to seat us. So we set off first this way, then that with a lot of back and forth arguing about the direction Google Maps wanted us to go. We eventually found our way to a seafood shop and restaurant called Blue Fjord. I don’t think they cater to many tourists and while our server tried hard, I seem to remember a few problems with our order. Still, the seafood was fresh and the meal filling and inexpensive.

Before I leave the Jewish Quarter, I want to comment on one more statue of Franz Kafka. Rather than a rotating head, this one, while featuring a complete Kafka also had him atop

a headless companion. Installed in 2003, it was, believe it or not, the first statue to honor Kafka in Prague. The sculptor, Jaroslav Róna, depicts Kafka as the narrator from his short story Description of a Struggle. The passage that inspired Róna reads, “And now – with a flourish, as though it were not the first time – I leapt onto the shoulders of my acquaintance, and by digging my fists into his back I urged him into a trot. But since he stumped forward rather reluctantly and sometimes even stopped, I kicked him in the belly several times with my boots, to make him more lively. It worked and we came fast enough into the interior of a vast but as yet unfinished landscape.”