What’s in a name? The natives lose twice.

Although Mormon settlers began expanding their settlements south from Salt Lake in the decade following the initial settlement, it wasn’t until 1863 that they reached the area we call Zion. The first settler to build a cabin in Zion Canyon was Isaac Behunin and it is he who, according to legend, sat on his porch one evening reading Isaiah, looked up at a scene something like this

and first called the space Zion.

It would be an understatement to say that Zion, both as a concept and as a physical place, has great importance to the Church of the Latter-Day Saints. They use the name Zion to signify either a group of God’s followers or a place where such a group lives. Latter-Day scriptures define Zion as the “pure in heart.” Isaiah 54:2 reads, “enlarge the place of thy tent; stretch forth the curtains of thine habitation; spare not, lengthen thy cords, and strengthen thy stakes” and some think this might have been the passage that inspired Behunin.

For some Mormons, Zion describes places where the pure in heart live together in righteousness. In a more tangible manifestation, geographical administrative units composed of multiple congregations within the LDS are sometimes called stakes of Zion. To a group that had been persecuted in the eastern states and viewed themselves not only as pioneers but as refugees, the term Zion itself is said to have taken on meaning as a symbol of Mormonism, embracing such qualities as courage, dedication to the cause, physical endurance, resoluteness, ingenuity, and faith. Thus, when Behunin applied the name Zion to the canyon in which he and a few others lived and worked, it was a profoundly important expression of cultural possession, not just personal ownership.

However, the canyon had a more ancient name. The Paiutes who had occupied the territory for centuries called it Mukuntuweap (MEW-kǝn-chew-ehp), which translates as “straight canyon” or “straight arrow.” In his 1872 USGS expedition, Powell, reported the name of the canyon as Mukuntuweap because he believed the native word to be the only proper and fitting name for a place he once described as having “the music of waters.”

If you read history from the perspective of the mostly Mormon Euro-Americans who settled the area, you will find repeated instances of passages like this one:

These canyonlands were once fearsome wilderness, but now they had been made habitable by Mormon pioneers at great sacrifice. Limited arable land, poor soils, periodic flooding (some of it catastrophic), and other factors made agriculture quite risky in the upper Virgin River region.

While undoubtedly true from the LDS pioneers’ perspective, it essentially disregards the fact that the Paiutes had, with some measure of harmony with the “fearsome wilderness,” found the region habitable for centuries.

Although relations between Mormons and Paiutes were generally peaceful, the intrusion of Euro-American settlers and the introduction of their aggressive agricultural practices meant the Southern Paiute people could no longer hunt or gather natural foods. Because they could no longer sustain their traditional way of life and because significant numbers of Paiutes died due to European diseases after the Mormons moved into this area, their numbers dwindled year after year. The surviving Paiutes eventually sought refuge by migrating south.

Few Paiutes remained in the area when, in 1909, President William Howard Taft officially deemed the area Mukuntuweap National Monument, using the original Paiute name. Given the centrality of Zion in their religious beliefs, it’s understandable that local residents were both angered and outraged. In fact, Mormons everywhere viewed the name as not merely insulting but as more evidence of continuing persecution. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints complained loudly and viciously against the name for many years. The natives had no such organized voice. In the end, just as their “taming of the wilderness” had effectively decimated or driven the natives away, the Mormon protests won the day and the National Park Service officially changed the name to Zion National Monument in 1917. It’s possible that among the few Paiutes who remained many, indeed, wept.

Timing matters.

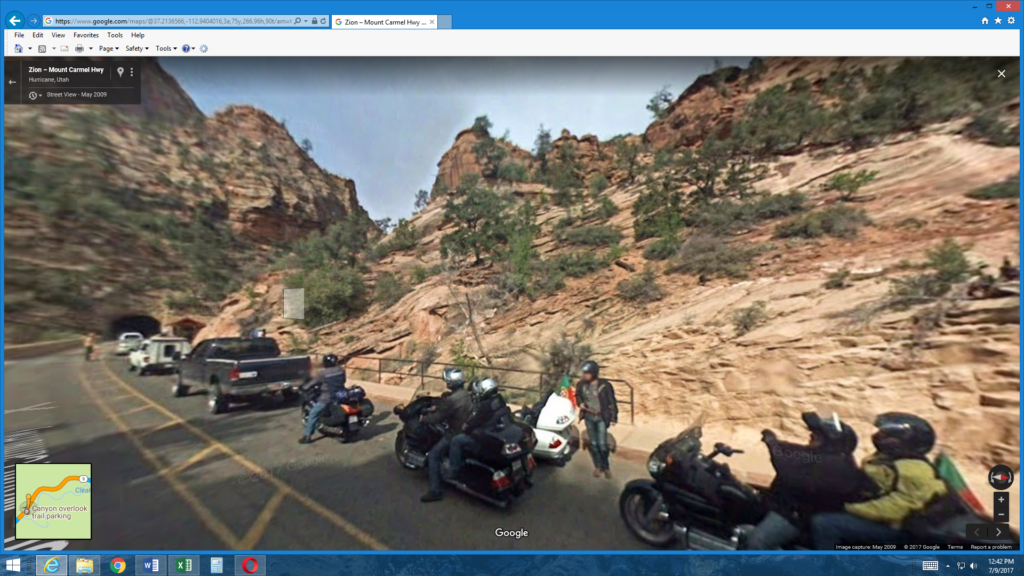

As I noted above, while I wouldn’t say that I frittered away the morning, I didn’t get on the road until a few minutes past 08:00 which was a bit later than had been my custom on this trip. All seemed well until I approached the entrance gate to the park a few minutes before 09:00. Here, about 500 feet from the ranger station, I encountered my first park entry delay and needed 10 minutes or so to clear the gate. But then came delay number two at the Zion-Mount Carmel Tunnel. The backup looked a little like this screenshot from Google maps:

When it was completed in 1930, the more than mile-long Zion-Mount. Carmel was considered a great work of engineering and was the longest tunnel of its type in the United States. The engineers understandably failed to foresee the increasing size of vehicles such as tour buses, motor homes, and trailers decades hence that would need to pass through it. It took until 1989 but a study by the Federal Highways Administration concluded that large vehicles couldn’t negotiate the curves of the tunnel without crossing the center line and causing accidents. Now, regular alternating closures reduce the tunnel to one way traffic and I reached it near the start of a westbound closure. The result was another 10- or 15-minute delay. (You avoid the tunnel if you enter the park from the west at Springdale.)

Once you pass through the tunnel and drive deeper into the canyon the difference between Zion and the other canyons – at least the ones I’ve visited – becomes immediately apparent. In those canyons, you begin at the rim and need to look or hike down to see or reach the canyon floor. Zion Canyon is essentially the opposite. The road leads to the floor of the canyon so the rock formations all loom above you.

If I wanted to view Zion as I’d seen the Grand Canyon, I’d have to hike up. Alternatively, I could have turned off at the small parking lot just to the left of the ranger standing between the yellow lines in the picture above. This marks the beginning of the mile long Canyon Overlook Trail where one can (but I did not) enjoy views like this one (taken from the website citrusmilo.com).

Although that view is spectacular, in some ways, it reduces the Zion experience to one that is, in broad strokes, little different from any other canyon. (I believe the serpentine road winding through this photo is the Zion-Mount Carmel Highway and the formation just to the right of center near the top of the photo looks like the one called the Three Patriarchs.) Looking at the rock formations soaring above you, on the other hand, fundamentally alters one’s perception of canyons – or at least it did mine.

Once I reached the area of the Visitor’s Center, I bumped up against another consequence of my delayed arrival – the park’s very limited parking. The main lot was already full and it looked as though the same was true of the overflow lot but fortune smiled on me when a chap walking across the lot alerted me to possibly the last spot in a back corner of the lot.

Because you’re inside, rather than above the canyon, you can’t drive to a viewpoint and look out as is the case at Bryce or the Grand Canyon. Once you’ve parked, your options are to spend all your time on foot or use the park’s system of shuttle buses to ride to one of the nine stops north of the Visitor’s Center and hike up the canyon’s various trails.

I’d signed up for a 14:30 tour of the sanctuary at Best Friends Animal Society (where I was staying in Kanab but more on this later) and, as I looked at the average time needed to walk each of the four trails I’d hoped to include, I realized, particularly after the 25 minute wait to board the first shuttle at the Visitor’s Center, that I’d have to choose between walking on all of them and reneging on my commitment for the sanctuary tour or skipping at least one of Zion’s trails and fulfill my commitment. This is the point when my late start now had its greatest impact. I chose to skip the longest of the four trails – the Riverside Walk to the Temple of Sinawava. Perhaps I erred. It’s likely I’ll never know.