I’d been up late learning about hoodoos so when the morning sun began to filter through the windows of my cabin, I obstinately pulled the covers over my face willing to trade a few minutes extra rest for the early start my plans for the day demanded. I’d met no delays entering any of the national parks and monuments I’d visited thus far and, since Zion National Park was less than an hour’s drive, I thought the extra sleep time would have little impact on the day. I was wrong. Timing is important.

As I once again started north on U S 89, I had some time to reflect about some of the places I’d visited to this point on the trip and was struck by a thought I found wryly humorous and perhaps mildly ironic. Here’s a partial list: Grand Canyon National Park, Walnut Canyon National Monument, Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Bryce Canyon National Park and the place I was about to visit, Zion National Park.

The first three all have canyons while, as I explained in the previous post, Bryce does not. There’s no mention of canyon in Zion’s name yet its two most prominent features are canyons – the eponymously named Zion Canyon and, in the park’s northwest, Kolob Canyon. So there’s no canyon in a park that has canyon in its name but two canyons in the park that doesn’t. Does that qualify as at least mildly ironic?

Before I go on, for those of you who don’t know the reference I’ve made in the title of today’s entry, I’ll solve the mystery with this video.

The Grand Design.

While the specifics might differ from one canyon to another, the general processes that create them – uplift and erosion with varying degrees of sedimentation – remain constant. Such is the case for Zion Canyon. (I didn’t visit Kolob Canyon.)

Here’s a brief look at Zion. Most of the rocks throughout the park – both within the canyon and outside it – are sedimentary. Near the beginning of the Triassic period (about 250 million years ago) Zion was a relatively flat basin near sea level. Over the ensuing 150 million years, sedimentation deposited the rock layers seen in Zion today.

Also in a previous entry, I touched on the two major periods of uplift – the first of which (Colorado uplift) began about 80 million years ago. Over those two major periods, Zion’s elevation rose from near sea level to as high as 10,000 feet above that.

Because Zion was near the western edge of the uplift, the streams, flowing rapidly down a steep gradient, tumbled off the plateau with great cutting force as they descended to the sea. The lead actor in this rock cutting drama is the North Fork of the Virgin River (named for Thomas Virgin who, in 1826, was the first Euro-American to see it). Its performance was so forceful that it carried away several thousand feet of rock that once lay above the highest layers visible today. In fact, the stream gradient of the Virgin River ranges from 50 to 80 feet per mile (or 0.9% to 1.5%). According to several sources, this places it among the steepest stream gradients in North America.

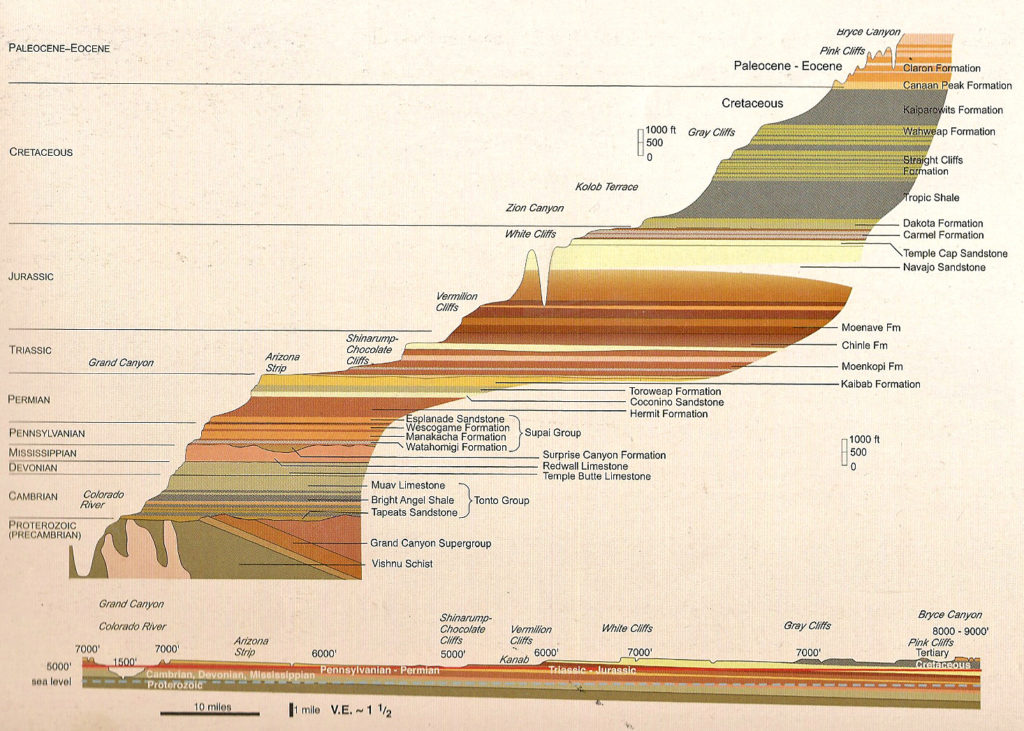

In the post about Bryce, I noted that it lies at the top of the Grand Staircase that the National Park Service describes as “the world’s most complete sequence of sedimentary rocks”. One way of thinking about this is that the series of cliffs stretching between Bryce Canyon and the Grand Canyon are like a sedimentary layer cake. The top layer of the rock at the Grand Canyon is the bottom layer of the rock in Zion and the top layer of the rock in Zion is the bottom layer of the rock in Bryce. Graphically, it looks like this:

(This graphic representation was taken from Doctor Jack Share’s website as was the photo below which he describes as one of the best (among the few) viewing spots to see the entire staircase. There are few of these places because the earth’s curvature often keeps distant areas out of view.)

Living in Zion.

Although the evidence is sparse, there are artifacts – such as flaked stone knives and dart points hafted to wooden shafts propelled by throwing devices called atlatls found in some caves and deeply buried sites – that provide clues that ancestral peoples inhabited the area in and around Zion perhaps as long as 8,000 years ago. Interpreting the existing evidence indicates these people lived highly mobile lives for millennia. This group of ancestral people appears to have begun forming settlements sometime between 500 and 300 BCE with the first appearance of efforts at cultivation – particularly maize and squash. Additional evidence suggests that these people were part of the Basketmakers culture that we first encountered in the Petrified Forest.

By the year 500, two distinct horticultural groups appear that archaeologists call the Virgin Anasazi and the Parowan Fremont (identified by the rivers – Virgin and Fremont – central to their settlements). The Virgin Anasazi seem to have been the more settled of the two. Evidence indicates they likely had a near total reliance on cultivated foods while the Parowan Fremont remained more reliant on wild resources to supplement their cultivated food.

Virgin Anasazi sites typically occur on river terraces along the Virgin River and its major tributaries, overlooking the fertile river bottoms where corn, squash, and other crops could be grown while Parowan Fremont sites are found at somewhat higher elevations farther to the north and west with fewer farming options but where they developed and cultivated a drought and cold tolerant variety of maize.

Near the beginning of the 12th century, a new group – ancestors of the Paiute and Utes – began emigrating into the area and by 1300, both the Virgin Anasazi and the Parowan Fremont disappear from the archaeological record. Over the two centuries, periods of both prolonged drought and catastrophic flooding likely made it nearly impossible for the two more settled groups to successfully compete for resources with the more mobile Paiutes and Southern Utes.

For the next four hundred years, these Numic language speakers were the sole occupants of this challenging landscape. Although the Southern Paiute planted maize, sunflowers, and squash, all these groups traced a highly mobile lifestyle moving seasonally to hunt game or collect ripe seeds and nuts.

The first Euro-Americans began to explore the area in the late 18th century gradually establishing the Old Spanish Trail that tracked north from New Mexico and followed the Virgin River for a portion of its length. Visitors to Zion today have an easier route to the canyon:

By 1847, Brigham Young led members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints to Utah Territory. (For linguistic variation and occasional brevity, I will also use the colloquial term Mormons interchangeably with Latter-Day Saints.) They first established settlements in the Great Salt Lake Valley but within a decade, Mormon pioneers were sent to settle the southern part of the territory and grow cotton in Utah’s “Dixie” with, as we shall see below, devastating consequences for the native peoples that had dwelled there for centuries.

Following his successful 1869 exploration of the Grand Canyon, John Wesley Powell returned to the area in 1872. He explored the areas around Zion Canyon, as part of western surveys conducted by the U S Geological Survey.

Note: In keeping with my 2022-2023 reformation of the blog into shorter entries, backdated to maintain their sequence, any comments on this post might pertain to its new configuration. See the full explanation in the post Conventions and Conversions.

These pictures are amazing!!!