This year I’d planned to visit to the Baltic Republics (Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland) in June that included a stay in Inari above the Arctic Circle on the summer solstice and a few days in the Netherlands. Unfortunately, the operator canceled this trip for lack of sufficient interest and I declined the alternatives they offered for lack of sufficient enthusiasm. Although I briefly considered an autumn trip to Iceland hoping to see the aurora, I vetoed the idea because of my planned extended return to Lisbon late in the year.

However, like an air bubble in a water cooler, an indistinct (and perhaps inaccurate) memory glugged up from the depths of my mental jug to its surface. It was this: Under optimal conditions, it might be possible to see the aurora from someplace as far south as Mackinac (pronounced Mack-in-awe) Island in the northern reaches of Lake Huron.

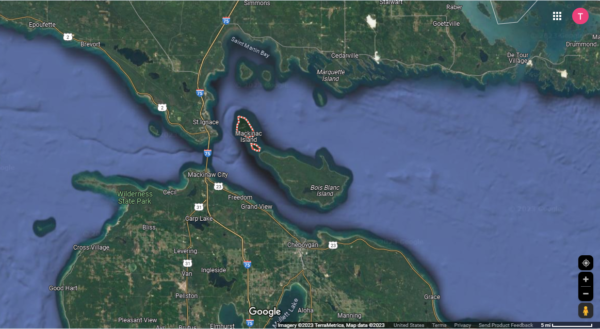

[Satellite view from Google Maps.]

Further research proved that seeing the aurora in this place, while possible, is a rare phenomenon. However, during this investigation, I also recalled that Mackinac Island is the location of Grand Hotel (The absence of the definite article is deliberate.)

and that the island and Grand Hotel were the principal locations of the movie Somewhere in Time – an unsuccessful film in its initial release that’s now considered a cult classic. The hotel operates from the beginning of May to the last weekend in October and in 2023 would host the thirty-third annual Somewhere in Time weekend. For me, attending this weekend would provide the opportunity to fulfill a promise I made years ago to an important person no longer in my life so I booked the room.

And then the Terps.

Most people who know me know I support University of Maryland athletics. As I’ve said on many occasions, “I’m not a sports fan. I’m a Maryland fan.” When I mentioned my plan for this weekend to a fellow Terps fan, he noted that Maryland’s volleyball team was scheduled to play at Michigan State and Michigan the following weekend. He neglected to remind me (and I forgot to check) that the Big Ten Field Hockey Tournament was also scheduled to be held at the University of Michigan on the same weekend as the volleyball games initially scheduled for Friday and Saturday November third and fourth.

Aha! I thought. I’ll fly to Detroit on 26 October, stay on Mackinac Island Friday through Sunday, drive around Michigan for the week and be able to root on the Terps before returning home the following Sunday. Then, after booking all my flights, hotels, and rental car, Michigan moved the volleyball game from Saturday to Sunday because its football team was also playing a home game that Saturday. (Had I remembered about the field hockey event, I would have initially booked my return for Monday. I opted not to change my plans.)

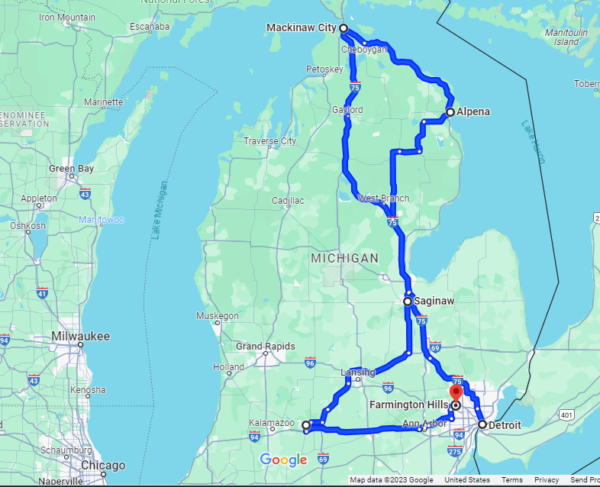

Another complication arose because not only Michigan but Michigan State had a home football game that first Saturday in November. This engendered a prohibitive cost for any hotel rooms in the immediate environs of both Ann Arbor and East Lansing. Thus, my general course around the state ended up looking more or less like this (as plotted on Google Maps)

Other than Detroit and, to a lesser degree Mackinaw City, the circles on the route represent the places I stayed – Alpena, Mackinac Island (my rental car stayed in Mackinaw City because cars aren’t allowed on Mackinac Island), Saginaw, Battle Creek, and finally Farmington Hills. This map outlines only the places I stayed not everywhere I visited. Although I generally prefer urban habitats and adventures, this is one trip where I won’t be livin’ for the city. Those reports are forthcoming but before I strap you into the passenger seat of that ride, I’ll take a brief look at Michigan’s geography.

HOMES.

If you are a person who works on American crossword puzzles, when you see this word in all caps, a specific thought is likely to pop into your mind. Looking at this

satellites.pro image of the United States, the section header’s acronym might be the nation’s most easily and readily identifiable internal geographic feature. The acronym, of course, identifies the Great Lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, Superior). If you then focus your attention on the state of Michigan, where all of this journal will occur, you should notice that it stands alone as the only state with lakeshore on four of the five lakes – all but Lake Ontario. (Not, Erie as I originally wrote. Thanks to Double D for catching my error.) Thus, it should make sense to you that, as I make the first day’s drive north from Detroit to Alpena, I’m going to focus my attention on the Great Lakes and explain how they came to be.

Those among you who have subjected yourselves to reading my essays on geology and geography may be expecting another journey into one or more geomorphic ages of our planet’s past. While I’ll briefly mention such a period, the formation of the Great Lakes doesn’t require a journey of such great temporal length.

About a billion years ago, mountains, spawned by a period of intense volcanic activity, covered the area that we now delineate as northern Wisconsin and Minnesota. As the mountains eroded, the volcanoes continued erupting intermittently spewing molten magma below the highlands of what is now Lake Superior out to their sides. The highlands sank and formed a mammoth rock basin that would eventually become Lake Superior as, over time, the rock tilted down from north to south.

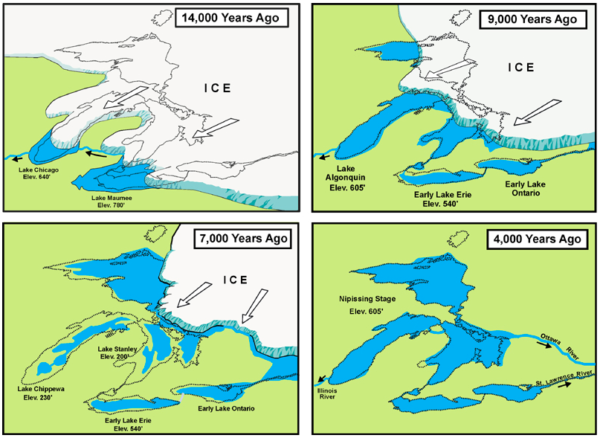

Eventually, the fire turned to ice and repeated periods of glaciation and deglaciation spread across North America over a period lasting more than five million years. All of the Great Lakes are proglacial lakes meaning, in this case, that they were formed by meltwater trapped against an ice sheet due to isostatic depression of the crust around the ice. (Isostatic depression occurs when large parts of the Earth’s crust sink into weak parts of the upper mantle from a heavy weight placed on the Earth’s surface. Glacial ice during continental glaciation fits that bill.)

Eventually, the ice retreats, the weight is removed, and the land rises in a process called isostatic or post-glacial rebound. If we were hovering above the part of the continent about 10,000 years before present (BP), we’d see the shorelines of modern Lake Superior start to develop.

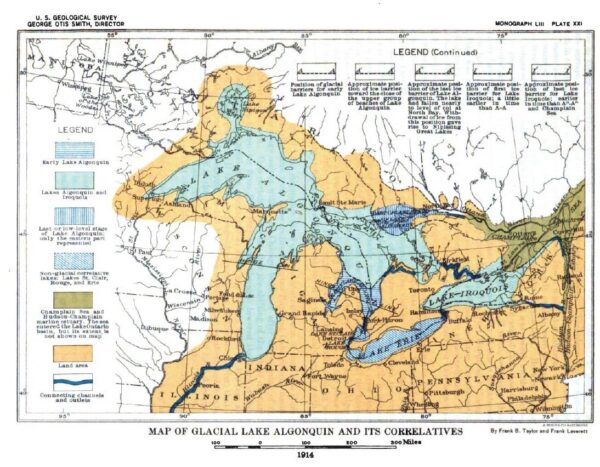

At this time, the lakes we now call Superior, Michigan, and Huron were part of two vast inland lakes called Lake Duluth and Lake Algonquin. These lakes later joined to form one vast lake as the glaciers retreated . This lake’s level was controlled by a single outlet on the south shore of Lake Huron.

[Map From USGS.]

About 7,000 years ago, the ice completed its retreat and the land to the southwest of Lakes Erie and Michigan rose high enough that the lakes no longer drained in that direction. Lake Ontario came into being, and the Niagara River became Lake Erie’s outlet. During this time, Lake Huron drained eastward out the Ottawa-Saint Lawrence rivers until about 5,000-6,000 years ago while Lake Michigan drained out the Illinois River near present day Chicago. It was a mere 3,000 years ago that the Great Lakes assumed their present shapes and drainages.

In the north, a barrier near Nadoway Point in Whitefish Bay began eroding and, about 2100 years ago, raised the level of the Saint Mary’s Rapids, separating Lake Superior from Lakes Michigan and Huron. From this time forward the levels and shorelines of Lake Superior have been controlled by the elevation at the Saint Mary’s rapids near Sault Sainte Marie.

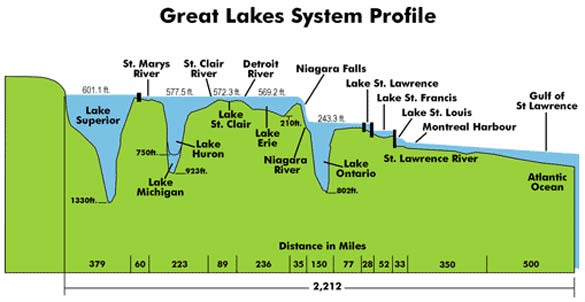

Four of the five Great Lakes are at different elevations,

[Profile from eekwi.org].

like a series of eastbound steps. The five individual lakes are connected to each other through channels, forming one system. Water continually flows from the headwaters of the Lake Superior basin through the remainder of the system. The Saint Lawrence River is the final link in a more than 2,000-mile-long water chain connecting Minnesota with the Atlantic Ocean. Together, they constitute the greatest freshwater system on Earth, holding an estimated six quadrillion gallons of fresh water (about 20% of the world’s surface level drinking water) while covering an area nearly half the size of Alaska.

The system is so vast that the lakes often behave like oceans manifesting coastal currents, (including rip currents) and showing occasional large tide-like changes in coastal water levels called seiches (something we first encountered in this post about Earthquake Lake in Wyoming) that are caused by prolonged strong winds and passing storms. Storm surges and edge waves also occur. Additionally, as the oceans do, the lakes moderate the temperature of the air and impact the amount of precipitation that falls around them.

In the next post, I’ll make an abbreviated visit to Alpena and arrive on Mackinac Island.

Isn’t Lake Ontario the only one that does not border Michigan?

You are correct, sir. And I have made the appropriate correction.