As the ninth Inka, Pachakutiq was not a builder of empire alone. He was also a builder – or at least he oversaw numerous important construction projects. Although excavations haven’t conclusively shown when construction began on Qorikancha, most archaeologists believe that it was built during the reign of Pachakutiq. This would make sense given his desire to have all the people of the Tawantinsuyu revere Cusco as a sacred site.

One indicator of that intent arises from designing the city in the shape of a puma – the zoomorphic representation of the earthly realm common to all Andean cultures – if that was, indeed, the case. Another indication would be the expansion of the Saqsaywaman complex which would not only be the logical place for the puma’s head but would elevate the external perception of the city if by nothing more than its very size. The third factor would be this most important project for the city itself – building the Temple of the Sun called in Quechua Qorikancha (or the Golden Courtyard). (Like all the other places, its actual name has been lost to history and you will see variant transliterations with the most common probably being Coricancha.)

If you recall the video about the city’s puma shape (in this post), you might remember that the speaker places the Plaza Huakaypata as the crucial center of the design and the departure point for the main roads to each of the four sections of the empire. However, although it’s less than a kilometer away, this isn’t the site of Qorikancha and you might wonder why this is so. Why would Pachakutiq not build his most important temple at the city’s most important spot? Archaeologists have offered two plausible explanations. First, elements of Inkan oral history refer to a temple built on this site by the Inkas’ progenitor Manco Qhapaq and there is some evidence of pre-empire construction.

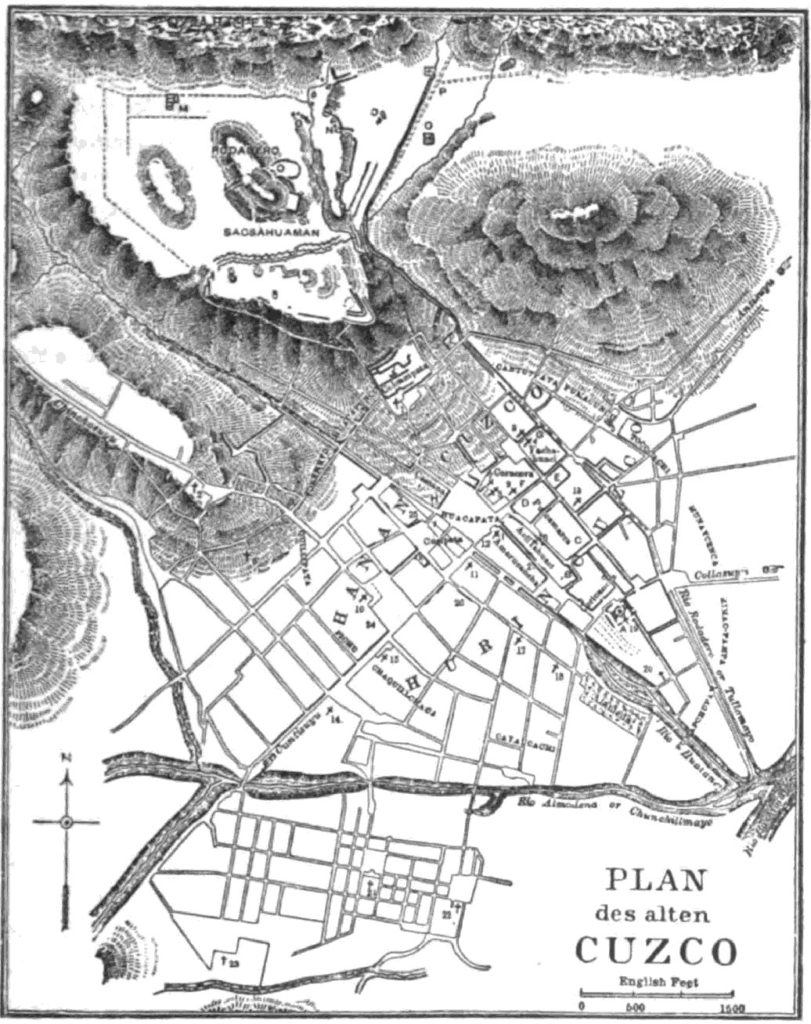

[Map of old Cusco from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

Second, in keeping with the idea of the city’s puma shape, if Saqsaywaman was the head, Qorikancha would have been located close to the confluence of the two main rivers – the Huantanay and the Tullamayo – and provided the puma’s tail. This would have accorded well with an essential element of the Inkan world view – that of symmetry and duality.

Zeq’e out this Wak’a.

In a previous post about Cusco, I mentioned the 41 or 42 Zeq’e – the straight ritual pathways radiating from Qorikancha to the four areas of the Empire – and the 328 wak’as or sacred places along those routes. If Qorikancha was seen as the source of the wak’as this would have elevated its status to that of highest importance. Imagine looking at the zeq’e from above and the complex evokes the image of the sun. In fact, its main temple was dedicated to Inti, the sun god.

Little of Qorikancha remains for the 21st century visitor – though this would have been true to some degree by the middle of the 16th century and completely so by 1654 when the Church and Monastery of Santo Domingo was consecrated above the Inkan ruins. In fact, as we entered the site I felt I was entering a Christian Church. However, we came quickly upon the work of the Inkas.

Once again, we are treated to the mastery and mystery of Inkan architecture and construction seeing how the large blocks fit precisely together with no trace of mortar. In the photo, I also tried to capture the perfect alignment of the windows and their characteristic trapezoidal shape. The shape and alignment of the doorways and windows allowed not only access but light to enter the interior spaces. The walls also lean slightly inward as they rise in height. This helped stabilize the structure in the event of an earthquake.

In the post Reclaiming Coca – It’s the real thing, I wrote “As a society that had no concept of money, the indigenous people of South America didn’t value metal and mineral resources in the same way as the Europeans.” This doesn’t mean that the Inkas didn’t value gold and the temples at Qorikancha were, perhaps, the ultimate display of how they perceived that metal’s value as we shall soon see. The very name we use includes the Quechua word Qori which means gold.

The other half of the name, kancha, describes the most common composite form found in Inka architecture. A kancha was a rectangular outer structure surrounding at least three rectangular single-story buildings with thatched roofs that were themselves placed symmetrically around a central courtyard. The form is found in common dwellings, palaces, and temples. Among the characteristics that set Qorikancha apart from the most representative forms of Inkan architecture were a curved wall (which we will see anon) and the use of gold throughout.

The walls of Inka structures were typically bare and unadorned though we do occasionally see niches such as those at Q’enqo. This was far from the case in the Temple of the Sun. Not only were the walls lined with niches

but reports say that both the interior and exterior walls of this temple were covered with 700 half-meter square sheets of gold each weighing 2 kilograms. The Inkas considered gold to be the sweat of the sun so they would have seen its use here (and perhaps the emeralds that at least one description claimed studded the interior of one of the perimeter walls) as particularly appropriate. This demonstrated the value they placed on the precious metal.

One can barely imagine the sight that would have greeted a traveler approaching the temple on a sunny day along one of the zeq’e. I think its majesty would have simultaneously inspired apprehension and awe.

Based on surviving accounts of the 16th century Spanish conquerors the temple was filled with ceremonial golden artifacts connected to worshiping the sun god including one jewel covered statute presenting Inti as a small boy with a hollow stomach that stored the ashes and vital organs of deceased Inka. The statue was carried into the garden each day before being returned to its shrine every night.

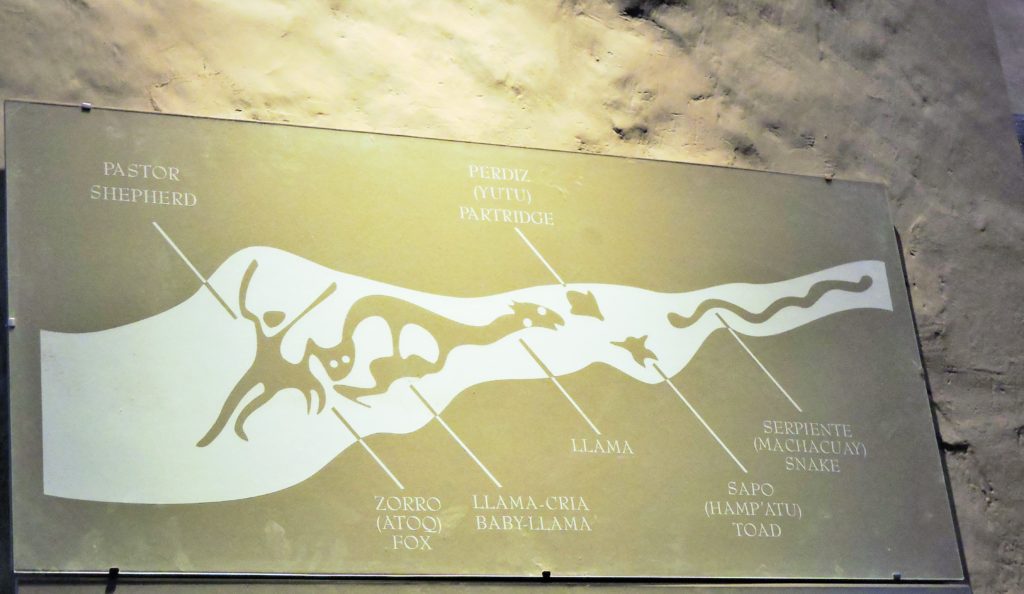

The garden, too, would have been a breathtaking sight. Everything in it – a large field of corn, llamas and their shepherds, pumas and various other fauna including insects was cast from gold or silver. Among the little that remains of all this splendor are these silver ears of corn.

[Silver ears of corn photo from the Denver Art Museum.]

But Inti wasn’t the only god worshiped at Qorikancha. In addition to the main temple, the complex housed five additional temples. These were dedicated to Viracocha (the creator god), Mamaqilla (the moon goddess), Chaksa-Qoylor (goddess of the planet Venus), Illapa (the thunder and lightning god), and Kuychi (the rainbow god). Each temple would have contained art and religious icons appropriate to worshiping that specific god or goddess.

As is the case with most significant Andean religious construction, Qorikancha was also an astronomical observatory. Of particular importance were observations of the Inkan constellations in Mayu or, as we call it, the Milky Way.

There was also a sacred stone from which the resident priests would track the sun using both natural and man-made landmarks across the horizon and a pair of towers placed to cast elongated shadows on the day of the summer solstice.

When this post continues, we’ll take a look at the fall of of the Inkan empire and the European destruction of Qorikancha.