A cemetery serendipity.

Theo van Gogh died on 25 January 1891 – a mere six months after his beloved brother. Theo’s official cause of death was listed as “dementia paralytica caused by heredity, chronic disease, overwork, sadness.” It’s commonly believed that his actual cause of death was syphilis. Theo was only 33. While Vincent was buried in Auvers, Theo was buried in Utrecht, about 50 miles from where the brothers were born in Zundert, Netherlands. His body stayed in Utrecht until 1914, when the family had it exhumed and transported to join his brother, and they were reunited.

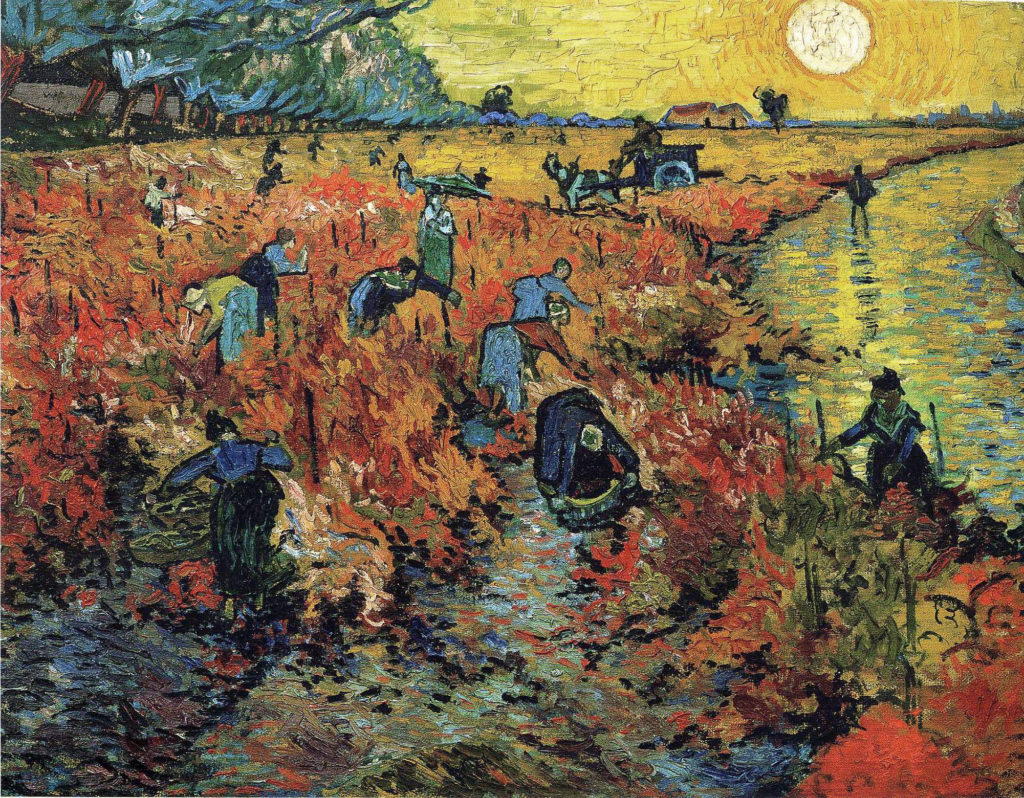

It’s widely reported that van Gogh sold but a single painting during his lifetime – The Red Vineyards Near Arles that now hangs in the Pushkin Museum of Art in Moscow.

But this doesn’t mean he wouldn’t have become successful had he survived the gunshot. Van Gogh had his first exhibitions in the late 1880s and his reputation began to grow steadily among artists, art critics, dealers, and collectors. In 1887 André Antoine hung a number of Van Gogh’s paintings alongside works of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, at the Théâtre Libre in Paris. In 1889 his work was described in the journal Le Moderniste Illustré by Albert Aurier as characterized by “fire, intensity, sunshine”.

Ten of his paintings were shown at the Société des Artistes Indépendants, in Brussels in January 1890 seven months before his death. Red Vineyards was among those paintings and it was there that Anna Boch purchased it for a reported 400 francs – a sum equal to about 1000 dollars in today’s currency.

Circumstances led to his burgeoning reputation suffering a brief setback. Theo’s death in January 1891 removed Vincent’s most vocal and well-connected champion in the art world. His widow Johanna van Gogh-Bonger was a Dutchwoman in her twenties who had not known either her husband or her brother-in law very long and who was likely a bit overwhelmed when she suddenly had to take care of several hundred of Vincent’s paintings, letters and drawings, together with her infant son, Vincent Willem van Gogh. Gauguin, with whom Vincent had a falling out in Arles, was not inclined to offer assistance in promoting van Gogh’s reputation and Johanna’s brother Andries Bonger simply seemed lukewarm about his work and was also not particularly helpful. Then Aurier, one of van Gogh’s earliest supporters among the critics, died of typhoid fever in 1892 at the age of 27.

A large van Gogh retrospective held at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery in Paris in 1901 helped to rebuild his reputation. Today, of course, Vincent’s paintings sell for tens of millions of dollars.

You can see more of Auvers here but before we leave, I need to share a coincidence so remarkable I had to take a photo. As we entered the small graveyard at the top of the hill behind the church in Auvers where the brothers van Gogh are buried, I stepped to my left to pass a few in the group who were walking too slowly for my liking. This tombstone, that I wouldn’t have otherwise seen, caught my eye.

Given that all of my paternal family came from Ukraine and that our family name before coming to the U S was Cryuchansky (or something like that), this “famille” is not related. But still…

Nothing to do with custard.

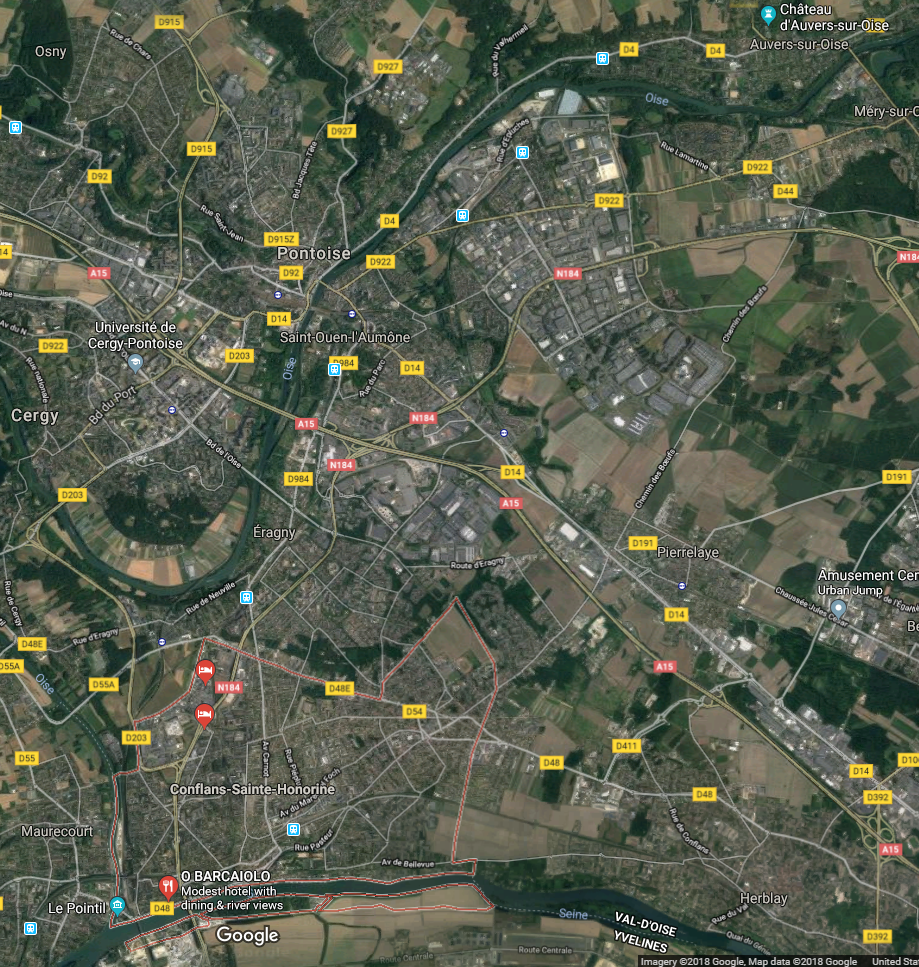

I finished breakfast early Friday morning and had a half hour or so to explore the area near our ship before we had to board the buses for Auvers. As you can see from the Google maps satellite image below, Conflans-Sainte-Honorine (outlined in red at the bottom left) isn’t a very big place.

And, to set the record straight, it’s named for being at the confluence of the Seine and Oise rivers which you can see at the spot marked “Le Pointil” – a memorial I’d see on my afternoon walk. (Somehow my brain looked at the name and broke it into two Spanish words con flans meaning “with flans” hence the pun of today’s title which I chose over “Auvers, Auvers can he be?”)

Conflans added Sainte-Honorine to its name sometime after 1082. Saint Honorina (Sainte Honorine in French) is, according to my cursory research, “the oldest and most revered virgin martyr of Normandy.” Although little is known about her, at least six communes bear her name.

It’s generally believed her martyrdom happened during the persecutions of Diocletian in the fourth century and that it occurred either at Mélamare or at Coulonces. According to legend, her body was thrown into the Seine and washed up near Le Havre where there is an abbey in her honor. (One source claimed her body washed up at Conflans but that didn’t seem to comport with the facts as far as I wanted to probe to uncover them.)

The most reasonable story for the addition of Honorine’s name (if there must be a reason) centers on those mid-9th century Norman invaders that Charles the Bald paid to leave Paris. When they were threatening the coast, the monks guarding Sainte Honorine’s relics decided to move them farther inland to Conflans. They remained in the castle there until it was destroyed after a siege in 1082 though the relics were preserved. (You can see the tower of the castle – called Tour Montjoie – in the photo at the top of the first Conflans post.) The monks then built a church in her honor and, at some point, the town added Sainte-Honorine to its name. She has become the patron saint of the river boatmen.

I set out toward the east along the Seine and had only walked 150 or 200 meters when I happened upon this small memorial.

I assumed but was unable to confirm that it honored French Resistance fighters though it could also memorialize Jews and other deportees.

After lunch but before we were scheduled to depart for Château de la Roche Guyon, I had time to walk in the opposite direction toward the point where the Seine and Oise rivers converge. On my way, I passed the floating chapel called Je Sers (I Serve) – an appropriate name given that its patron saint is Saint Nicholas. (Yes, that’s the Turkish – okay, Lycian – born saint who somehow morphed into fat guy with a flowing white beard in a red suit).

The boat served its original purpose of shipping coal from 1919 to 1936. In April of that year, the Entraide Sociale Batelière (Boatmen’s Mutual Assistance Society) purchased the ship to convert it to its present use. The founding abbot Joseph Bellanger bestowed its current name and, with the blessing of the Bishop of Versailles inaugurated its service in November of that year. Today it is moored at the Quai de la Republique where it serves not only boatmen on the river but also has provided a haven and respite for Tibetan refugees since 2014.

Quickening my pace, I hustled toward the place where the rivers converge hoping I’d be able to find a vantage point for a photo showing the confluence. I couldn’t do that in the time I had but I did see this monument near that spot.

Looking at the dates, and as nearly as I can determine from the strained efforts of Google Translate to render French descriptions into English, this is a memorial to river barge men who died in World War I and World War II.

And it’s mainly because of its role in World War II that we will visit Château de la Roche-Guyon this afternoon. I’ll share the details of that visit and the history of the castle next.