Making a case against Van Gogh’s suicide.

In the early part of July 1890 Vincent was seemingly in good health. No one reported any breakdowns, he wasn’t writing about madness, and he was painting a lot. However, Theo, who knew him better than anyone, must have seen something amiss in at least one of Vincent’s letters. On 22 July Theo wrote to Vincent, “I am a little afraid that there is something troubling you or not going right. In this case drop in to see Doctor Gachet.” Vincent replied with a letter that only talked about his painting.

The standard account is, like almost all the other “early accounts” of van Gogh’s suicide, based on the testimony of Adeline Ravoux. Adeline, you will recall, was 13 at the time. She wrote this in 1956:

That Sunday he went out immediately after breakfast, which was unusual. At dusk he had not returned, which surprised us very much, for he was extremely correct in his relationship with us, he always kept regular meal hours. We were then all sitting out on the café terrace, for on Sunday the hustle was more tiring than on weekdays. When we saw Vincent arrive night had fallen, it must have been about nine o’clock. Vincent walked bent, holding his stomach, Mother asked him: “M. Vincent, we were anxious, we are happy to see you to return; have you had a problem?”

He replied in a suffering voice: “No, but I have…” he did not finish, crossed the hall, took the staircase and climbed to his bedroom. I was witness to this scene. Vincent made such a strange impression on us that Father got up and went to the staircase to see if he could hear anything.

He thought he could hear groans, went up quickly and found Vincent on his bed, laid down in a crooked position, knees up to the chin, moaning loudly: “What’s the matter,” said Father, “are you ill?” Vincent then lifted his shirt and showed him a small wound in the region of the heart. Father cried: “Malheureaux, [unhappy man] what have you done?”

“I have tried to kill myself,” replied Van Gogh.

These words are precise, our father retold them many times to my sister and I, because for our family the tragic death of Vincent Van Gogh has remained one of the most prominent events of our life. In his old age, Father became blind and gladly aired his memories, and the suicide of Vincent was the one that he told the most often and with great precision.

If you’re interested, you can read the entirety of her recollection of life with Vincent at this site.

However, a 2011 biography called Van Gogh: The Life by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith posits an alternate theory.

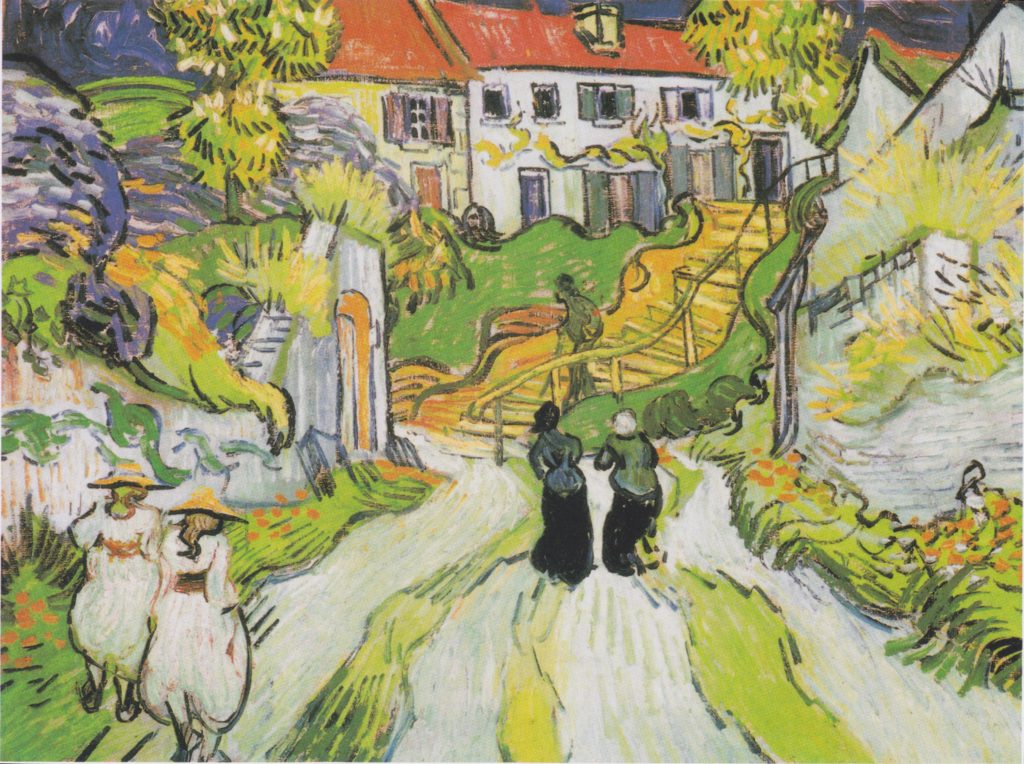

They agree that Vincent was shot on 27 July and they agree with Adeline Revoux’s assertion that van Gogh left in the morning and returned injured and bleeding in the evening. Had he, as she asserted, “gone to the wheat field where he had painted previously”? Perhaps he climbed these steps just behind the Auberge Ravoux that day

and that he depicted in this painting.

[Saint Louis Art Museum, Saint Louis, Missouri].

Perhaps not.

After those points of agreement, their claims and hers diverge substantially. In their book, the writers assert that two brothers named Secretan bullied Vincent. The older of the two, René, who was 16 in 1890, admitted as much in a 1956 interview. He said that he and his brother put snakes in Vincent’s paint box and salt in his coffee and would also torment Vincent by throwing fruit at him.

René said he modeled his behavior on his hero, Wild Bill Cody, whose Wild West Show he had seen in Paris the year before. He even bought a souvenir costume and accessorized it with an old, small-caliber pistol that looked menacing but often misfired. “It worked when it wanted,” René is reported to have joked. It was just “fate” that it wanted to work the day it shot van Gogh who he claimed had somehow stolen the gun.

But it isn’t merely Secretan’s odd interview that they use to support their theory. They take a closer look at the claims of Adeline Ravoux noting that she didn’t speak on the record until 1953 when she was 76 years old. When she did, she mostly channeled the stories her father, Gustave, had told her half a century earlier. But, they assert, her story changed with each telling.

A deepening mystery.

In looking at the contemporary accounts of the shooting, they found none that mentioned suicide. The stories only reported that van Gogh had “wounded himself.” No one knew where he would have gotten a gun; no one ever found that gun, or any of the other items he had supposedly taken with him (canvas, easel, paints, etc.). His deathbed doctors, an obstetrician and a homeopathist admitted to being able to make no sense of his wounds.

Continuing to build their case, they cite a report by art historian John Rewald who had traveled to Auvers in the 1930s when the painter’s death was still remembered and who interviewed many local people. Later, Rewald confided to several people, including at least one on the record, a rumor he had heard there: that some “young boys” had shot Vincent accidentally. The boys never came forward, he was told, because they feared being accused of murder, and Vincent, perhaps in a depressive phase and indifferent to his death, chose to protect them.

This is effectively their conclusion. “The accepted understanding of what happened in Auvers among the people who knew him was that he was killed accidentally by a couple of boys and he decided to protect them by accepting the blame,” they wrote.

But their evidence doesn’t stop with this testimony and supposition of his emotional state. There was no suicide note. Rather, his pocket held a draft of a regular letter he’d sent to his brother on the day of the shooting.

Finally, they point to the nature of the bullet wound that the witnesses of the time, including Doctor Gachet, described as a clean, pea sized wound. Additionally, neither doctor noted any black powder burns on his hands, any stippling, or any other marks on the skin around the wound. A gun available for civilian use at that time would have been filled with black powder and almost certainly would have left such residue if used in a manner consistent with Adeline Ravoux’s description.

After publication of their book, other van Gogh scholars researched their claims and published an article that held to the idea of suicide. So it was that, in 2014, at Smith and Naifeh’s request, handgun expert Doctor Vincent Di Maio reviewed the forensic evidence surrounding van Gogh’s shooting. Di Maio noted that, because he was right-handed, van Gogh would have had to have held the gun at a very awkward angle to shoot himself in the left abdomen.

The location of the wound presents another awkward conundrum. Vincent had enrolled in the Académie des Beaux Arts in November 1880. While there, he studied anatomy and the standard rules of modeling and perspective. It’s puzzling that someone with even a basic knowledge of anatomy would attempt suicide by shooting himself in the location of Vincent’s fatal wound.

“It is my opinion that, in all medical probability,” concluded Doctor Di Maio, “the wound incurred by van Gogh was not self-inflicted. In other words, he did not shoot himself.”

At this time, most van Gogh scholars continue to discount the version of events Naifeh and White Smith present, claiming that the authors make too many assumptions with too little real evidence. Of course a cynic might maintain that there’s some value to the art world in perpetuating this image of Van Gogh. Right or wrong Naifeh and Smith certainly raise interesting questions.