The First Fleet

(How did we end up here?)

Our morning began with a lecture focusing on the history of the settlement of Sydney but included some information that was an overview of Australian history from the arrival of the First Fleet.

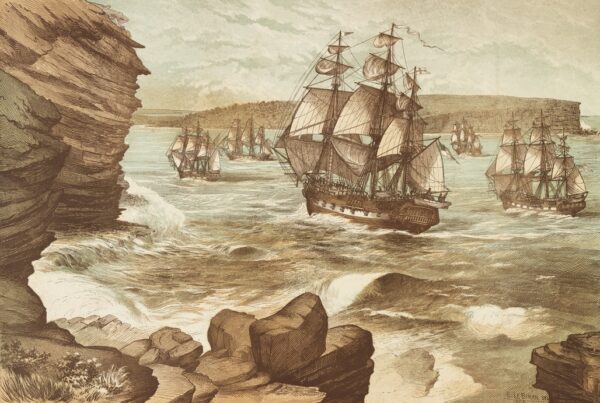

[Edmund Le Bihan lithograph – First Fleet entering Port Jackson 26 January 1788]

(The First Fleet was a company of eleven ships that carried the first group of convicts and military personnel from the United Kingdom to Australia. While I may return to some superficial discussions of Australia’s settlement as a penal colony, it’s been covered in great depth in many other sources including Robert Hughes’ seminal work The Fatal Shore. For now, I’ll note that many people died on the voyage, that the British Crown gave no consideration to the skills that would be needed to successfully colonize the continent {and the people suffered greatly as a result}, and that, for political expedience and necessity, they gave no recognition to the humanity of the Aboriginal people who, as we will learn, had lived successfully on the continent for at least as long as 60,000 years.)

Acknowledgement of Country

M, a retired history teacher and our site coordinator, delivered the lecture. It was, as I recall, absent a statement such as this,

I acknowledge Gadi Country, her lands, sea and sky, we acknowledge her custodians, the people of the Grass tree, their kin the Wangal, Bidjigal, Cabrogal and Cammeraigal who often visited this Country to connect and share. We offer our respect to their Elders both past and present.

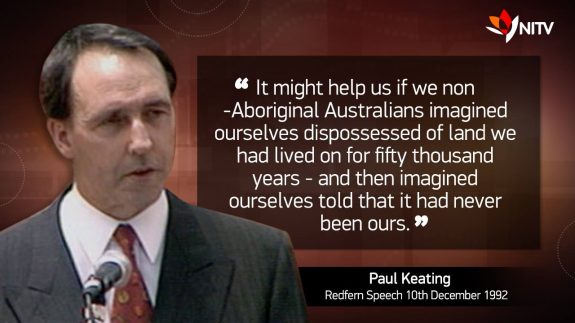

Although this voluntary statement known as the Acknowledgement of Country has its contemporary origins in the 1970s, it began to become a part of the Australian cultural mainstream in the 1990s under the government of prime minister Paul Keating in what he called the reconciliation decade.

[Image from facebook.com/NITVAustralia]

(You might recognize the above statement as similar to one I made at the end of my first post. Because I will be visiting and passing through the Country of many of the First People of Australia, I will issue and Acknowledgement of Country periodically. However, I believe that posting an Acknowledgement of Country for each of them would become burdensome to the reader. Thus, I endeavored to acknowledge all Countries in a single comprehensive statement. I wrote one statement as a measure of convenience and it is not intended to attenuate the contributions of any of Australia’s First People to their Country.)

Politically, the Acknowledgement arose out of the 1992 case known as the Mabo decision that rejected the principle of “terra nullius” that the British used to occupy and conquer Australia. The decision also acknowledged the traditional rights of the Meriam people of the Torres Strait Islands to their land. In its far-reaching decision, the court also held that native title existed for all Indigenous People. It marked the beginning of a process that will almost certainly reshape Australian society even if the movement is sometimes barely perceptible. We’ll learn more about these events and the principle of terra nullius throughout this journal.

Lachlan Macquarie

For now, let’s return to the present and the preparation for our bus ride. As we’d learned the previous day, M had a distracting tendency to stray from his main points. The principal thrust of my notes from this talk indicate that he seemed to have a particular affinity for Australia’s fifth governor – Lachlan Macquarie (surname pronounced muh-QUARRY).

Macquarie was certainly a man of his time and was for centuries among the country’s most honored and respected of Australia’s early governors – and is often called, in fact, the Father of Australia. He is often credited as the first person to use the name Australia. However, as a man of his time, his actions, seen through a more modern lens, like those of many historical figures, make him rather less honorable and respectable. Let’s take a slightly deeper look.

[Image from Wikipedia – Public Domain]

While some in Australia have reevaluated Macquarie’s place in the nation’s history, I think M’s opinion and portrayal of him was probably settled in his early education and it can be difficult to abandon perspectives we learned as children even as new interpretations of prior events arise. In this instance I sensed his view was closely aligned with the one presented in the Dictionary of Sydney:

Few governors of New South Wales are as favourably remembered as Lachlan Macquarie, and for a variety of reasons. He has passed into the history books as a builder, an innovative reformer who created ‘an ordered civil society’ in Sydney Town, and the man who gave Sydney its first local currency, in the form of the ‘holey dollar’ and the ‘dump’.

If one takes a parochial conqueror’s view of European colonization, Macquarie’s accomplishments were impressive and myriad. (The number of place names bearing his name or that of a family member clearly demonstrate both that and perhaps an inclination to self-aggrandizement.) In addition to creating the first currency and establishing the colony’s first bank, after his return to England, “Macquarie listed 265 works of varying scale which had been carried out during his period as governor.” These included a new barracks, a new hospital, and the roads to Paramatta and South Head. Of course, he achieved most of these accomplishments over stolen land and on the backs of convict labor and although he brought some reforms to the System as it was known, it was still a system based on exploitation.

It’s also worth looking at how that same publication describes his relationship with the local Aboriginal people:

Macquarie was interested in the welfare of the Sydney’s Indigenous inhabitants, and some of his policies have been interpreted as an expression of his ‘humanitarian conscience’. He organised a village at Elizabeth Bay for the ‘Sydney Tribe’, a farm at George’s Head for Bungaree and the Broken Bay people, the Parramatta Native Institution, and the annual meeting with the Eora peoples at Parramatta. Despite this, he was also responsible for giving orders for the military operation that resulted in the Appin massacre in which at least 14 men, women and children of the Dharawal people were brutally killed.

It’s noteworthy that the passage begins by lauding his interest in the “welfare of Sydney’s Indigenous inhabitants” because, from a 21st century perspective some people view him as a mass murderer. Still others view him as having engaged in genocide. In his own words, Macquarie was, at the very least, quite literally a terrorist. On 14 May 1816, he issued a proclamation published in the Sydney Gazette:

And although it is to be apprehended that some few innocent Men, Women, and Children may have fallen in these Conflicts, yet it is earnestly to be hoped that this unavoidable Result, and the Severity which has attended it, will eventually strike Terror amongst the surviving Tribes, and deter them from the further Commission of such sanguinary Outrages and Barbarities.

One element of his terror campaign was ordering his troops to hang up the bodies of any Aboriginal men killed during the operation. At least two of them later had their heads hacked off and sent to Scotland.

[Site of Appin Massacre from Monumentaustralia ]

While perhaps well intentioned, even his organization of “a village at Elizabeth Bay for the ‘Sydney Tribe’, a farm at George’s Head for Bungaree and the Broken Bay people, the Parramatta Native Institution, and the annual meeting with the Eora peoples at Parramatta” was misguided and showed a lack of understanding of the indigenous culture. I don’t know if it’s fair to say that the notions of tribal culture and chiefdoms were anathema to the Gadi people of that country but they were almost certainly concepts that didn’t exist in their culture or societal structure.

As you travel around the continent with me, I’ll try to provide a better understanding of the indigenous cultures and how not only their world view but their systems of agriculture, aquaculture, and land management contributed not only to the survival but the flourishing of the world’s oldest culture.

For now, take a break as we board the bus and head off to learn about one of Sydney’s iconic structures – the Harbour Bridge. (In referring to specific proper names I will defer to the preferred local spelling. In general contexts, I will use the American spelling. Thus, you will see Sydney Harbour referring to that specific place but harbor when referring a place on a coast where vessels find shelter.)

I’m enjoying your interpretation and perspective on Australian / Sydney history and Australian Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander culture. I think you get it better than most. I look forward to reading more.

Thanks. It hasn’t been easy.