The group had more free time after our rather strange lunch – or strange until it became the norm. Although my notes don’t have legible confirmation, I believe we had our lunch at a restaurant called Pürstner where the specialty is spaetzle which is, in some ways, the Austrian equivalent of mac and cheese. The two initially strange aspects that became the norm were that we were offered choices from a limited menu and that we were restricted to any combination of appetizer, main, and dessert but could only combine two courses. It seemed strange because those who chose appetizer-main had to watch while those who selected main-dessert finished their meal. It also gave a bit of an odd advantage to couples where one could order appetizer-main and the other dessert-main, sharing the opening and closing courses so they each had a taste of all three while those who weren’t similarly attached had to make do with two. It was, nevertheless, a heavy lunch and merited some extensive walking about the city.

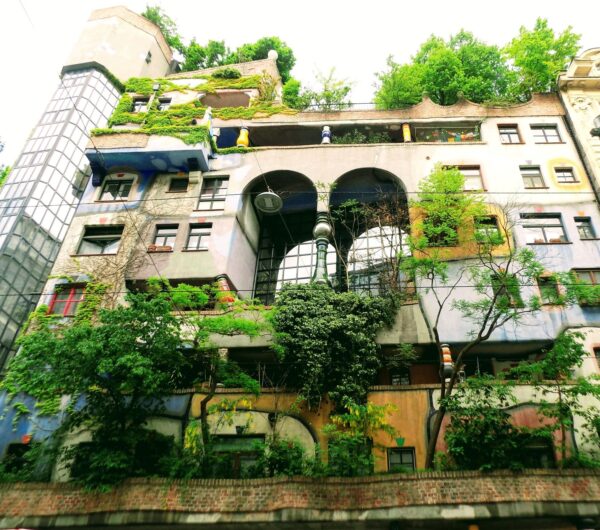

Stopped in my tracks on the way to the Fälschermuseum.

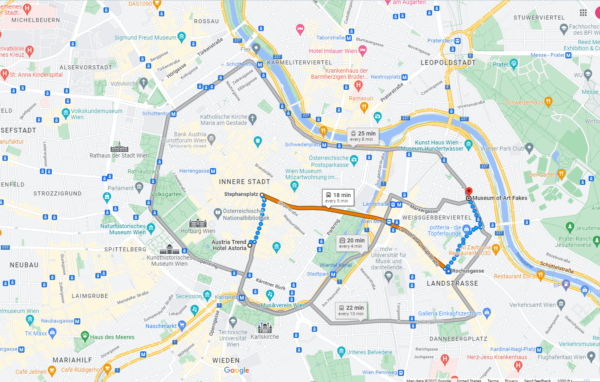

A quick interaction with the HereWeGo app told me that a walk to the Fälschermuseum was a manageable two kilometers but because I wanted to try and squeeze in some other sites and possibly one other museum, I decided to cut the walking distance in half by using the Metro. Here’s my route courtesy of Google maps.

I don’t think it was a visit to Atlas Obscura that put the Fälschermuseum on the list of Vienna attractions because, if it had been, I would have been prepared to walk past the Hundertwasserhaus just a block or so away. It might have still surprised me but at least I would have been expecting to see it.

Apparently, this building is (understandably) something of an attraction because I wasn’t the only one taking pictures.

The building is one of several in and around Vienna designed by Friedrich Hundertwasser. Born Friedrich Stowasser in Vienna in 1928 to a Jewish mother who decided to baptize him as a Catholic, Stowasser began his artistic endeavors at age 15 gaining some notoriety in the mid 1950s for his painting style. Wikipedia’s biography has this description:.

Hundertwasser’s original and unruly artistic vision expressed itself in pictorial art, environmentalism, philosophy, and design of facades, postage stamps, flags, and clothing (among other areas). The common themes in his work utilised bright colours, organic forms, a reconciliation of humans with nature, and a strong individualism, rejecting straight lines.

He remains sui generis, although his architectural work is comparable to Antoni Gaudí (1852–1926) in its use of biomorphic forms and the use of tile. He was also inspired by the art of the Vienna Secession, and by the Austrian painters Egon Schiele (1890–1918) and Gustav Klimt (1862–1918).

He changed his given name several times throughout his life finally settling on Friedensreich. (This can translate into English as peaceful realm.) The surname Hundertwasser, that he chose in 1949, seems to be something of a pun since sto in Czech means hundred or hundert in German. He retained wasser (water) because it was an essential classical element.

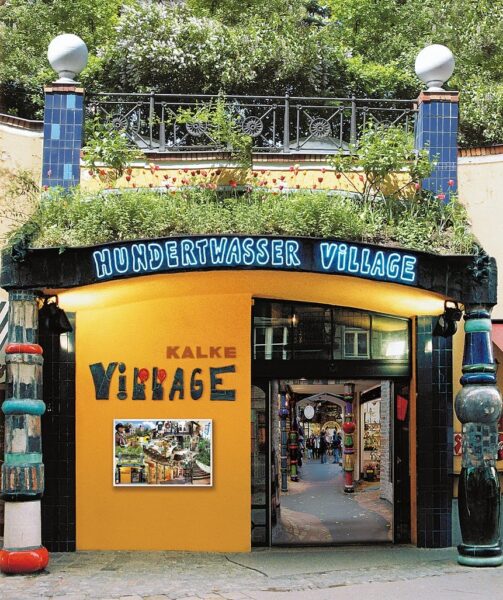

The city of Vienna owns the Hundertwasserhaus and leases the 53 apartments within. Thus, visitors can read about it and gawk at the exterior but it’s not open to the general public. Looking at the building, it’s difficult to discern any straight lines and this wavy motif apparently carries on in the apartments themselves even to their undulating floors. (“An uneven floor is a melody to the feet,” he once said.) Visitors can enter the Hundertwasser Village

but I found little of interest there.

Like all of his buildings, it’s intended to be a conversation with nature. Not only do Hundertwasser’s ‘tree tenants’ appear all over the place, some of them are apparently rooted in the flats themselves. The roof is also covered with vegetation.

I found one last amusing (and insightful) tidbit about Hundertwasser. Apparently, he typically wore unmatched socks and when asked the reason replied by asking, “Why do you wear the same socks?!”

Die Fälschermuseum.

First, the translation:

Yes, art fakes. But this small museum occupying the lower level of its building contains more than just art. In fact, its “most valuable” artifact is almost certainly Konrad Kujau’s forged Hitler Diaries that he sold to Stern Magazine in 1983 for 9.3 million deutschemarks (about $3.7 million U S or $10.85 million in 2022).

The museum opened in 2005 inspired by the work of one Edgar Mrugalla who also supplied the first works for the museum to display. Mrugalla, who died in 2016 at age 84, was one of the world’s most famous forgers producing more than 3,500 paintings during his life – all of them forgeries. (Although I found two web pages citing “…a study that shows that roughly half of the works of art sold throughout the world might be forged – 70% of Chagall’s, 90% of Dali’s and numerous van Gogh’s.” I couldn’t find the study itself and, therefore, will not speak to its validity. I also don’t recall seeing anything in the museum about Han van Meegeren – perhaps the most famous {or infamous} art forger of the first half of the twentieth century.)

Then, there’s the work of Tom Keating who claims to have forged over 2,000 paintings while planting what he calls time-bombs in his replicas to be discovered later, invalidating the forgeries to any duped collector. He claims he does this in protest against the corruption of the gallery scene.

It’s interesting to learn of the different types of forgeries as explained here (or in a photo in the album linked below). The museum has a no photos policy though they didn’t mind when I admitted that I’d taken photos of some of the explanatory signs. I found this YouTube video that’s interesting. Even eliminating the longish introduction, it’s still about 20 minutes long.

The first concert of the tour.

The program guide from Earthbound Expeditions for Sunday night’s concert read,

“Mozart Ensemble String Quartet

In Vienna’s oldest concert hall, the Sala Terrena – where Mozart once performed!”

That’s an exciting piece of information for anyone with even a light interest in Western classical music. But there’s so much more .

Let’s start with the building that houses the Sala Terrena, the Deutschordenshaus. The Deutscher Orden (Teutonic Order) was founded in Acre in 1190. Sometime in the early 13th century, construction on the Deutschordenshaus began – though I can’t say what, if any of that original building remains. Most of the exterior including the church

dates from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Although he was not part of the Teutonic Order, when Mozart’s employer, Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo brought his retinue from Salzburg on 16 March 1781, they stayed at the Deutschordenshaus. The 25 year-old Mozart knew he was a rising star and chafed under the Archbishop’s regimented demands and limitations including restricting his ability to perform outside the residence. It was at this place and time that Mozart resigned his position (much to his father’s dismay) and Colloredo’s steward, Count Arco, literally kicked Mozart out the door on 25 June. However, it seems Mozart had moved out of the Archbishop’s quarters in May. So, Mozart both lived and played in the Deutschordenshaus.

Many of Vienna’s concert venues have seen performances by the giants of classical music but housing one great composer isn’t enough for the Deutschordenshaus. Sometime in the early 1860s (possibly on his first visit to Vienna in 1862) Johannes Brahms was also a guest at the Deutschordenshaus. I found no report of Brahms playing or conducting in the Sala Terrena.

The Sala Terrena is on the ground floor adjoining the church in the photo above and was designed and painted in the second half of the 18th century.

The program began with Mozart’s Quartet in G-Major. He composed the first three movements at age 14 when he was on tour in Lodi, Lombardy and it’s sometimes called Lodi Quartet. The fourth movement, a rondo, was added later – perhaps as late as 1773.

They followed this with the Andante from Schubert’s ‘Rosamunde’ quartet in A-Minor. This movement is based on incidental music Schubert had composed for a play by that name written by Helmina von Chézy that premiered in December 1823.

The final piece before the brief intermission was Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. Originally composed for a chamber ensemble of two violins, viola, cello and double bass in 1787, its formal title is Serenade Number 13 for strings in G major. The familiar title comes from an entry Mozart made in his personal catalog. No one knows when it was first performed but it wasn’t published until 1827. A quartet performance sounds like this.

The final piece in the program was the fourth Quartet in C-Minor from the six compositions in Beethoven’s Opus 18 collectively known as the Lobkowitz Quartets. These were his first string quartets composed on a commission by his friend and ultimately a benefactor Joseph Franz Maximilian, 7th Prince of Lobkowitz.

My brief notes say that it was a magical setting and featured excellent musicianship.