The Wonder of it all

In my conversation with the folks on the ferry from Mackinac Island they asked me why I’d chosen to stay in Saginaw. I told them that I had two specific places I wanted to see in that city. One was the Castle Museum and the other was to see the “Stevie Wonder Rock”.

(Stevie Wonder was born Stevland Hardaway Judkins in Saginaw where he lived until he was four years old when his parents divorced and his mother moved to Detroit with Wonder and his two siblings. His premature birth was complicated by retinopathy that led to his blindness. A self-taught musician, he signed his first record contract at age 11 and was given the moniker Little Stevie Wonder by Motown producer Clarence Paul.

I don’t know enough about Saginaw to understand what, if anything, the location of this small monument signifies but it’s in what seemed to me like an out of the way residential neighborhood that, unlike the tribute mural I’ll see later in Detroit, takes some considerable effort to find. It looked a little bleak to me but that may have been related to the time of year and the chilly morning air.)

Visitar um castelo. Ou não.

Since the full name of the museum on this day’s itinerary is the Castle Museum of Saginaw County History, you might wonder what attracted me to it from relatively distant Maryland. First, there’s the building itself. The building’s architect, William Martin Aiken, designed it to reflect the homeland of the region’s earliest European settlers who were mainly French fur traders. Intended to evoke a French chateau, Aiken also incorporated elements of Italian Renaissance and Gothic styles.

Twice rescued from demolition, first in the 1930s then again in the 1970s, the city’s original 1898 central post office has been repurposed to this new use and is now on the National Register of Historic Places.

The museum itself first appeared as a radar blip to consider while I was perusing the list of Michigan sites on R-A’ s website where it’s described as having “weird things, like peep holes for the postal inspector to watch the workers sort the mail. Pretty nice for a local history museum.” Since peepholes weren’t quite enough to draw me there, I did a little additional research and found that it had a temporary exhibition featuring another famous Saginaw musician, the great jazz saxophonist, Sonny Stitt.

Although born in Boston, Massachusetts, as Edward Hammond Boatner, Jr., his father, Edward, Sr. put him up for adoption as an infant and he was quickly adopted by the Stitt family in Saginaw. Sometimes viewed as a Charlie Parker imitator Stitt ultimately developed a distinctive style that you can hear below and in more than 100 other recordings if you’re so inclined. Here’s Stitt’s version of the Gershwin classic, I Got Rhythm.

Of course, in keeping with the tone of the trip established Monday, when I reached the museum I saw this.

I’ve got a coat and two pair of plans.

Foiled by yet another Michigan closure, I fired up the RA app on my phone and, concentrating on places that were either entirely or principally outdoors, looked for and found some alternative places to visit to occupy my day. First up, Midland Michigan’s Tridge. As the crow flies, Midland is roughly 21 miles northwest of Saginaw. As the car drives, it’s a more L shaped route of about 29 miles requiring about half an hour.

So, what is The Tridge? According to cityofmidland.gov,

The Tridge is the formal name of a three legged wooden footbridge spanning the confluence of the Tittabawassee and Chippewa Rivers in Chippewassee Park in Midland. The Tridge opened in 1981. It consists of one 31-foot (9.4 m) tall central pillar supporting three spokes. Each spoke is 180 feet long by 8 feet wide.

The Tridge is one of Midland’s largest tourist attractions and people often travel from all over the country to visit it! Its three legs span out to Chippewassee Park, Saint Charles Park (Old Red Coats) and the Farmer’s Market areas.

Okay. I’ve seen the Tridge. What’s next?

Saint Louis – the town with its own tombstone.

This is a story of rampant unregulated pollution. Saint Louis is close to the geographic center of Michigan’s lower peninsula and sits on the banks of the Pine River. These geographic advantages likely contributed to the establishment of the Michigan Chemical Company there in 1935. Over the ensuing four decades, the company which became Velsicol Chemical, was the town’s largest employer.

It’s all but certain that problems from the company’s waste discharge were bubbling underground for some time but the first major issue, while unrelated to local discharge, erupted in May 1973 when workers accidentally shipped bags of polybrominated byphenal (PBB) – a fire retardant produced under the name FireMaster – to a Farm Bureau feed center near Battle Creek instead of another of the company’s products NutriMaster. The toxic PBB was then mixed into feed and distributed to farmers across the state setting the stage for one of the worst chemical / agricultural disasters in the state’s history.

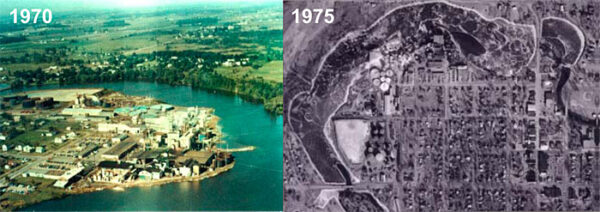

[Aerial photo from Interstate Technology Regulatory Council].

It took nearly a year before a federal scientist identified PBB as the cause of the gruesome deaths and deformed births that were plaguing Michigan farmers. This eventually led to the slaughter of 23,000 heads of cattle and nearly two million chickens. Sadly for Michigan residents most of them had consumed PBB laced food by this time and as recently as 2019 an Emory University study estimated that fully 60 percent of Michiganders have elevated levels of PBB in their systems. PBB has been linked with breast and liver cancers and thyroid and kidney diseases.

But this wasn’t the only problem the chemical plant generated for Saint Louis. During the Second World War, the company manufactured DDT for the U S Military and it continued producing the product long after the war’s end. In the 1950s it began dumping copious amounts of industrial waste directly into both the Pine River and at other ground sites nearby. As all animal life in the river died and local gardens did the same, the state government finally took action against Michigan Chemical’s parent company Velsicol.

The company shut its Saint Louis plant in 1978 eventually demolishing and burying everything from towers to pipes to railroad tracks. This burial included thousands of tons of DDT, PBBs, and other chemical waste.

[Aerial photo from WCMU.org].

As part of a legal settlement with the state in 1982, the company paid a 38-and-a-half-million dollar fine and agreed to “contain its contamination.” According to Ed Lorenz, political science professor emeritus at Alma College, “They contaminated a lot of stuff, but they had good connections, politically. And so, while they got penalized like here, they struck this deal they’d shut down and demolish the plant on site, and if they did that, they’d be able to walk away scott free even though they’d contaminated the food chain of 8 ½ million people.” In other words, by sowing mass confusion, people in power commit collusion.

The contamination of the site remained at such a high level that in the year the lawsuit was settled a judge decreed the need for a permanent granite marker as a warning.

While the marker originally sat outside the site itself, because a disaster like this can’t be put in the hands of fate, residents of the town had it moved to its current location on the grounds of the Saint Louis Historical Society in 2013. It sits adjacent to a small museum. Of course when I was there,

the museum was closed.

My Tuesday adventure continues in the next entry.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kukës

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026