(You got to get back to the land.)

It’s a new morning in Kakadu and we have one final activity (or as RS calls it a “Field trip class”) in the park before we board our bus for the three-hour plus return to Darwin. We’d start the day at Burrungkuy – a site I hoped I’d find particularly interesting. Burrungkuy is a place of kunbim – Aboriginal rock art and I anticipated that it would not only buttress my understanding of the area’s culture but that it might also serve as a synaptic connector (or possibly disruptor) between the notions I held about the similarities and differences between the First People of the Americas and the First People of Australia.

Some of the traditional caretakers of this Country still live privately elsewhere in the park. They have consented to leaving this place open to visitors who they hope will learn how their ancestors visited and sheltered here -gathering and sharing food, perhaps playing, and perhaps performing ceremonies. Current evidence shows that people were using these shelters from at least as long as 22,000 years BP and as recently as the 1960s.

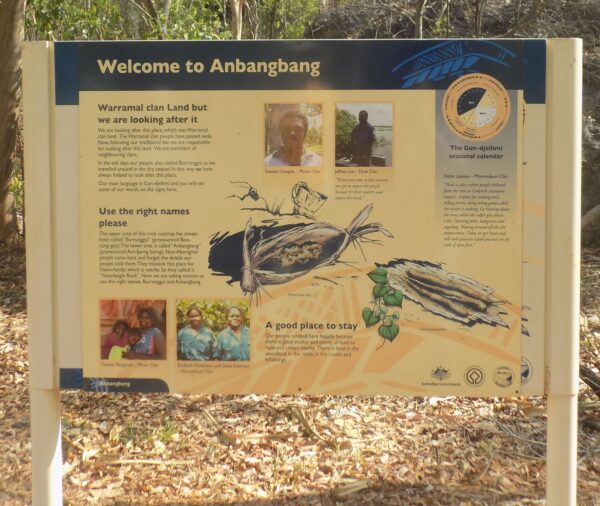

Walking to the main art site called Anbangbang (pronounced Arn-barng-barng) we learned from this sign

that it’s being tended by several clans including the Mirrar, Murrumbur, and Djok because none of the members of the Warramal clan, who were its traditional caretakers, are still living. Care of the land has passed to these surviving clans.

On our way to the site, we passed this nest of green tree ants –

a traditional and still eaten bush tucker delicacy that are high in protein, vitamin C, iron, zinc, and magnesium. Their abdomens are said to have a strong flavor of citrus. We didn’t stop to snack on them along the way and I was quietly relieved that we’d be leaving the park before we might have that chance.

Graphs and glyphs and thousands of years

The oldest known rock art in the United States dates to between 10,000 and 15,000 years BP and most of it is in the form of petroglyphs. The oldest known rock art at Anbangbang is at least 20,000 years old and most of this art is pictographic. The primary definition of a pictograph is “an ancient or prehistoric drawing or painting on a rock wall.” Petroglyphs are rock carvings made by pecking directly on a rock surface. As you can imagine, the latter are much more permanent than the former.

The two main factors that will degrade petroglyphs are people (who carve a new message or simply deface them) and erosion which usually requires time – and lots of it. People will paint over pictographs (and this happened regularly at Anbangbang) but simple weather can also diminish its vitality. Sunlight will make it fade. Rain might wash some of it away and so on. And, even comparing Native American pictographs to Australian Aboriginal pictographs, those additional thousands of years would take an inevitable toll. Thus while I was occasionally able to get a sharp view like this one,

just as often I had to strain to see the images.

Not only do the techniques differ but another signal difference between the petroglyphs of America’s First Nations and the pictographs of those created by the Australian First People is that the meanings and intents of the former have been lost to the mists of time while today’s living descendants of these artists can likely read their meaning even if there are no living Warramal to do so.

In the video, the artist first mentions that his totem is called Namarrkon who is an important ancestral being who is responsible for the violent lightning storms that occur every tropical summer. Namarrkon began his journey at Garig Gunak Barlu (Coburg Peninsula) to a rock shelter in the sandstone of Arnhem Land. Here he removed an eye and placed it high on the cliff at Namarrkondjahdjam (Lightning Dreaming), where he sits waiting for the storm season whose approach was traditionally signaled by the arrival of his children in the form of the brilliantly colored Leichhardt’s grasshopper.

[From Wikipedia By Stitchingbushwalker – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, ]

In Kunumeleng, he ascends to the sky where he resides through Kudjewk on storm clouds created by the Rainbow Serpent. From this vantage point he continues watching the people to ensure that they adhere to proper behavior and religious practices.

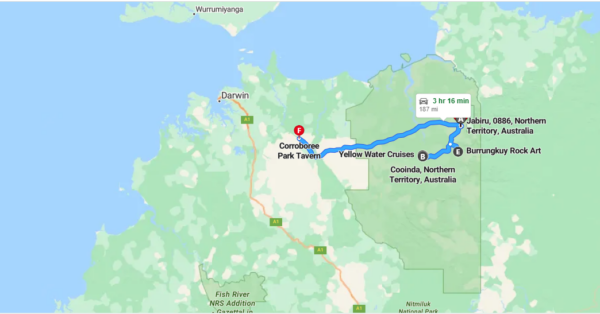

As we prepare to leave Kakadu, I’ll remind you that in the previous post The swift river ran I mentioned the National Geographic publication that called Kakadu one of the world’s life changing places. Although I found it beautiful and I learned a lot I can’t honestly say that I found it life changing. The map below from Bing shows the park’s borders and the places we visited.

I’ll posit that our brief visit left so much of Kakadu unseen that the place had little opportunity to change my life.

The secret lives of termites

I’m sure some of you reading this post remember this classic moment from the movie Crocodile Dundee.

I bring this up because when we were on Kangaroo Island, our bus driver pulled us to the side of the road to look at this termite mound.

On our way from Kakadu to Darwin, we stopped to look at this termite mound.

In fact, there were many this size at this location.

The termites that constructed this mound and the others nearby were likely cathedral termites (Nasutitermes triodiae). Of course, this merited a little research so I’ll share some of what I learned.

First, this is probably nowhere near the biggest of these mounds since the tallest are said to reach as high as seven meters. One of my fellow RS travelers snapped this picture of me standing near it.

I’m about 160 centimeters tall (or short depending on your worldview) so based on this shot I’d estimate that the mound, impressive as it looks, is between three and four meters in height. Try to imagine one twice that size.

The size and shape of mounds are influenced by climate, soil conditions, and the need for efficient air circulation. The mounds function like lungs by removing carbon dioxide and excess humidity from the nest. On the other hand, they’re hard. Maybe not as hard as concrete but harder, I think, than you might expect. And what are the construction materials? They use a combination of termite saliva, feces, and clay guided by a feedback mechanism involving air flow and odor concentrations.

And how sturdy are they? The structures can last between 50 and 100 years and they have an important role in the ecosystem – improving soil properties, increasing nutrient availability, and enhancing water movement through the ground while their hardness provides protection from predators. (You keep a knockin’ but you can’t come in.) Naturally, some nymphs will develop into the soldier caste as an added layer of defense for the nest.

The largest caste – worker termites – harvest and store dead grass in the mound’s outer chambers. This ensures a consistent food supply for the nest through a season when fresh grass might be unavailable. Their ability to digest cellulose and lignin – those tough plant components indigestible by most herbivores gives them a significant survival advantage in the harsh Australian environment.

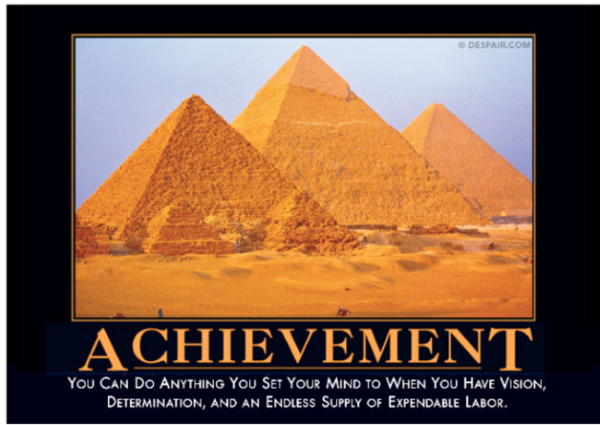

The third caste of termite in the mound will be the reproductive kings and queens. Sometimes these will head off and start a new nest but here’s the kicker. Queens can live up to 25 years and lay up to 30,000 eggs per day. That thought brought to mind this Despair, Inc. poster I once had hanging in my office.

Darwin’s respite

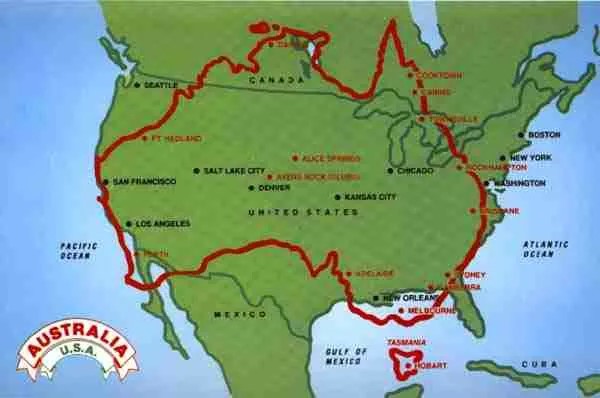

As we head to Darwin, I’ll give you your fin fact of the day. Perhaps you recall this ANBG Map I included in the post a multitude of people and yet a solitude

showing that Australia and the United States are closer in size than one might imagine. Here’s another indication: Our next stop, Darwin, is the capital of the NT. It’s closer to Indonesia’s capital of Jakarta than it is to Canberra – Australia’s capital city. (In fact, it’s also closer to Dili {East Timor} and Seri Begawan {Brunei} than to Canberra.)

We’d arrive in Darwin in time to check in to our hotel and freshen up before piling back onto the coach for our supper at the Darwin Trailer Boat Club. This, for me, would be a nice change from hotel dining (even though I’d broken away on my own in Adelaide). Billing itself as a Darwin institution, this casual eatery sits right on the water at Fannie Bay. (Tomorrow, we’d have “Dinner Own arrangements” so that pleased me even more.) My banana prawn salad with a local beer or ale was fine but the view at sunset

was spectacular.

While you’re waiting for my report on Darwin, here are some additional photos for your amusement and viewing pleasure.