If you have your own car and want to drive from Alice Springs to Uluru you should be able to complete it in about four and a half hours. Our RS itinerary had our coach departing the hotel at 07:00 and arriving for lunch at the “Ayers Rock Resort Town Square at 13:00.” (Departing at 07:00 meant breakfast at 06:00 and bags waiting to be loaded onto the bus by 06:45.) Perhaps to atone for a barely reasonable starting time and turning a four-and-a-half hour drive into one that lasts six hours, our drive made a pair of stops along the way – a rest stop at Stuarts Well and its three legged camel

and morning tea at Erldunda Roadhouse.

(I won’t tell you whether I had tea or another beverage akin to the one suggested in the photo above. I’ll only reveal that I wasn’t thirsty when we left.)

Reaching the Red Center of Australia

I acknowledge that I am on the land of the Anangu People. I acknowledge their custodianship. The Dreaming is still living. From the past, in the present, into the future. Forever. I would also like to pay respect to the Elders past, present, and emerging and extend that respect to other Aboriginal people present.

I don’t think any of us were paying close attention to the time or how long we’d been on the road (I know I hadn’t been) but as we drove closer to Uluru we passed this formation in the distance and I began to feel some excitement on the bus.

It’s not Uluru. In fact, M, our site coordinator cheekily told us local folks call it Fool-A-Ru. The local Anangu people call this place Artilla but you are more likely to see the name Mount Conner applied to it. (The formation is different from Uluru and Kata Tjuta which are monoliths. Artilla is an inselberg – a type of isolated rock formation that stands out from the surrounding landscape due to erosion – and it is on the private 1,000,000 acre Curtin Springs Cattle Station owned by the Severin family since 1956.)

For the local Indigenous People of the area, Artilla is home to the Terrible Ice Men or Ninya. The people are wary of offending them because of their power to bring cold weather. While it’s not viewed in the same way as its neighbors, it’s one of three similar formations in this area. The others are, of course, Uluru, which is some 150 kilometers distant and Kata Tjuta another 50 kilometers to the west.

You can fly over Artilla in the video below. The flight portion begins at about the 2:30 mark.

On to Uluru – Kata Tjuta National Park

It was getting close to our scheduled lunch stop at Ayers Rock Resort. Don’t be fooled into thinking that because it has retained Ayers Rock in its name that it isn’t an enterprise of the Aboriginal People of the region. The owner is the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation (ILSC) – a corporate Commonwealth entity established under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Act 2005. The ILSC’s primary purpose is to assist Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in acquiring and managing land and water-related rights. In the case of Ayers Rock Resort, they retained the older name because the local community wanted to keep the name Uluru limited to the rock and the land itself. They recommended maintaining the resort’s pre-acquisition name.

As it was with most of the meals on this trip, for me, lunch was quickly consumed and forgotten. I set out about the town to find an ATM because M had told me that when we went to Uluru for our sunset viewing, I’d have the opportunity to purchase some art but that I’d need cash and I only had about $50. Both of them were broken and even the cashier at the grocery store was unable to add cash back when I tried to purchase a Kit Kat.

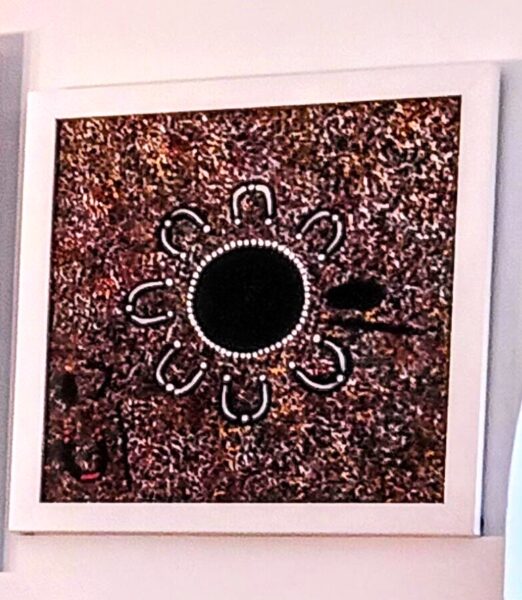

Then, we were walking to board the bus and I saw a woman sitting on the grass by some of her paintings. One of them caught my eye and, though she asked for $30, I gave her $40. She signed the back and I had a new painting for my collection.

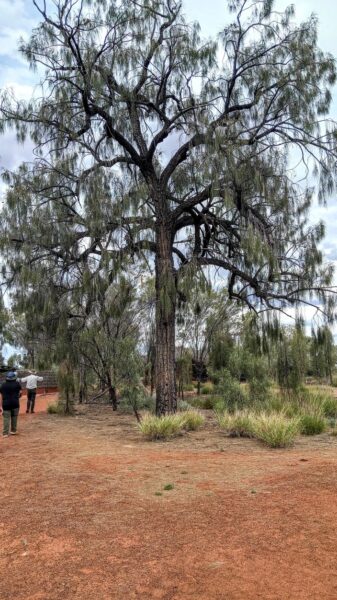

Before we reached the monolith itself, we stopped at the Aboriginal Culture Centre where there was much to read and learn about the Anangu people and life in this part of Australia. Sadly, there was only one photo allowed – that of a desert oak –

a tree (like the ghost gum we saw in Alice) that has great significance to the local people. Its seeds and cones are a food source, it captures and stores moisture thereby providing a reliable water source in a generally arid environment, and it makes excellent firesticks that are difficult to extinguish once lit. It has a strong cultural presence as well. There are at least two important Dreaming stories – The Desert Oak Dreaming and the Digging Stick Dreaming associated with it.

And now some words from your friendly amateur geologist

(And a shower has changed the lustre of his land)

After an hour or so at the Cultural Center, we were off to have our first encounter with Uluru itself. It’s one of the most well known symbols of Australia and “What was it like?” or some variation was among the most common questions people asked me on my return. My response was that as massive as it might appear in photos,

its weightiness is even larger in person. (Yes, the day was that cloudy and dull so while we weren’t able to see Uluru in its full redness, we felt it nevertheless. Or I certainly did even if not in quite the way that J had suggested I might. And, there are some who would consider us fortunate to have seen it in its more natural shade. The red shade so closely associated with it is, in fact, rust.)

As I’ve done with other landscape features we’ve met on this journey, I’ll first present you with the western scientific reading of the forces that created Uluru and I’ll follow that with a look at some of the Dreaming Stories of the Anangu People regarding the arkose monolith.

Uluru began its life some 550 to 600 MYA with the Petermann orogeny. This mountain building spanned a period of about 110 million years and was a result of the relatively rare process known as intracratonic orogenesis. This means the plate movement occurred within the Australian continental block rather than the more common orogenic processes of plate tectonics or volcanic activity.

These mountains, once as high as the Himalayas, eroded over a relatively short period of 20 to 25 million years. This happened so rapidly in part because their accelerated orogenesis created steep slopes that will erode quickly particularly when there’s a lack of vegetation to anchor the soil. Still, those millions of years of erosion buried and compressed the weathered granite into an extremely hard type of sandstone called arkose.

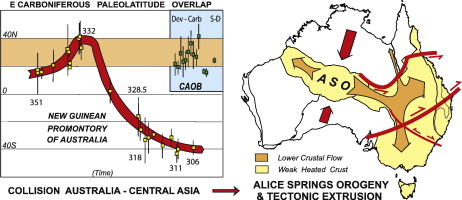

About 330 MYA, the Alice Springs Orogeny – a second intracratonic event

[From Science Direct]

lifted the buried arkose back to the surface while turning it nearly 90° in the process. This makes Uluru a bit like an iceberg – more of it is below the ground (at least two-and-a-half and perhaps as deep as six kilometers) than the 348 meters that’s above the ground.

North-south compression and shortening characterized the Alice Springs orogeny and uplifted the MacDonnell Ranges we saw there. A few hundred kilometers away at Uluru, the softer sandstone that lay atop the arkose gradually eroded away. Uluru as we see it today has resisted extensive erosion because of the homogeneity of its composition and lack of jointing.

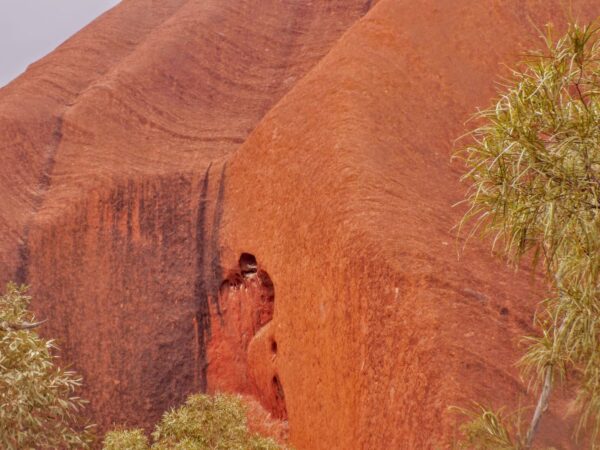

In its most well-known pictures, Uluru usually has a markedly red appearance.

However, on days when the weather is cloudy (as it was for much of our visit), Uluru looks more like this

which is, as I noted above more representative of its natural color before weathering and oxidation (rusting) of iron minerals in the rock. The color is most intense when the sun is shining.

In the next post, we’ll take a simplified look at some of the Dreaming stories associated with Uluru.