The Neanderthal bonus (Moscow and Me supplement five)

Often, in researching the topics I include in this blog, I unearth topics that inevitably take me down a path that eventually becomes informationally extinct. Sometimes vague traces remain in the archive of my mind and other times there are no artifacts at all. Then there are the times that I happen upon a topic I find fascinating but one that has no clear or coherent path to permit its inclusion in any post. Such is the case with this post which stems from an article I read in Discover magazine while researching the ancient hominins of western Russia. The information is tangential at best and in the worst case, irrelevant, but I found it fascinating so I include this bonus entry in the hope that you will find it so, too.

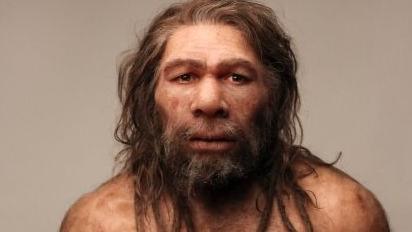

The hidden Neanderthals.

Let’s begin with the proposed timeline we saw in the post Humans arrive in Beijing. Recall that it shows isolated populations of Neanderthals migrating from Africa into parts of Eurasia 560,000 years ago and some 260,000 years before the first modern humans arise. These populations remained isolated for another quarter million years more or less until Homo Sapiens began their own diaspora about 60,000 years BP and within about 20,000 years Neanderthals disappear from the fossil record at least as a unique species.

[Image from thetimes.]

Based on extensive reviews of radiocarbon dates associated with Neanderthal fossils and artifacts, this is the time frame most archaeologists assign for the extinction of our evolutionary relatives. The reason for their disappearance remains unknown but thereŌĆÖs no uncontested evidence for the species persisting past that time particularly where they were coexisting proximally with modern humans.

Byzovaya.

Is it possible that in remote near polar reaches of Eurasia, Neanderthals outlived their western counterparts by 7,000 years? Or even 10,000?

This is the proposal made by a team of researchers┬Ā in 2011 after studying the site of Byzovaya in RussiaŌĆÖs Ural Mountains.

[Map from Researchgate by Jan Mangerud.]

As you look at the map, note that the distance to Sungir is about 1,700 kilometers (1,050 miles) and Kostenki is another 600 km farther. The question is whether this is enough physical distance to have kept a group of Neanderthals isolated enough from Homo Sapiens that they outlived by millennia their European counterparts.

According to the authors of a 2011 study the answer is yes. They claim Neanderthals survived in Byzovaya until about 31,000 years ago – 9,000 years after the presumed extinction date. There are some problems and questions about this conclusion though.

First, their analysis is based strictly on the artifacts unearthed at the site. While animal bones are present, no human fossils of any kind have been found there. Second this band would constitute not only the longest-lasting Neanderthals, theyŌĆÖd also be by far the farthest north – nearly 1,100 km (700 miles) beyond the speciesŌĆÖ currently known northern limit. The nearest sites with DNA-confirmed Neanderthals are far to the south in Okladnikov (3,000 km to the southeast) and Denisova (3,200 km south).

However, if this was a group of Neanderthals, it’s not unreasonable to presume that seclusion could have shielded them from extinction, at least for a few millennia, and delayed their discovery by modern-day archaeologists as well.

I report. You decide.

Byzovaya sits on a river bluff in the foothills of the Ural Mountains which form the border between Europe and Asia. At 65 degrees latitude, the site is about 160 kilometers shy of the Arctic Circle and 1,800 km from Moscow.

[Photo from Discovermagazine.]

Since the first excavations in the 1960s, Byzovaya has been explored several times by different research groups who have uncovered more than 300 stone artifacts and 4,000 animal bones, mostly from woolly mammoth. Handcrafted stone tools and butchered bones indicate the presence of some species of humans.

In 2011, a French-Russian team produced 33 radiocarbon dates from animal bones found with the artifacts resulting in dates ranging from 34,600 to 31,400 years old. This result isn’t particularly surprising since the Urals hold other archaeological sites of similar age with a few even older sites within the Arctic Circle. However, the general assumption has been that only H. sapiens had the smarts and technology necessary to survive at these high latitudes.

Do the tools tell the tale?

Since there are no human fossils and hence no DNA, the answer has to lie with the tools. Unfortunately, the conclusion you reach depends on your interpretation of the evidence.

[Photos from science.org].

Favoring the Neanderthals: the scraping and cutting tools (seen above) resemble those long associated with European Neanderthals. Favoring H. sapiens:┬Āthe fact that even those living┬Ā in northern Africa and southwestern Asia between 200,000 and 45,000 years ago made tools like those of Neanderthals.

But another point in favor of the Neanderthals lies in the fact that stone tools attributed to anatomically modern human societies, which date to as early as 45,000 years ago in southern Russia, include small, rectangular blades and spear points. Not only have such implements not been found at Byzovaya but in nearly all surviving instances of evidence of close H. sapiens and Neanderthal interaction, both styles of toolmaking are present.

Of course, it could simply be that the Byzovaya people were a group of modern humans who simply preserved an older Stone Age culture. Coexistence of the two in a harsh environment is also a possibility. Or, the Byzovaya people might have been related to the Denisovans or some other group of hominins who wandered far to the north and went quietly extinct.

Or maybe you have a different idea altogether.

Next, I’ll take you a bit farther west and look at the Olympics in some Nordic locations.

-

It’s just a shot away – Prizren

March 6, 2026 -

Some things looking better, baby – Getting into Kosovo

March 4, 2026 -

Here, where the sky is falling – Kuk├½s

March 2, 2026 -

That’s when we fall in line ’cause we got Berat

February 27, 2026 -

Walking on the big stuff – a climb to Tragjas

February 25, 2026