Roads are turning journey with them – A little learning next.

We left the Mercado and set off to a family run Campo de Ourique restaurant that has been serving the neighborhood in this location for more than a century – the intriguingly named Casa dos Passarinhos or House of Little Birds. It’s about a kilometer distant by the most direct route but Ines took us through some side and back streets that might have lengthened or shortened the walk. I can’t say which.

It would probably be a bit of an understatement to say our meal here was sumptuous. We started with a series of entradas (starters) – queijo fresco (a cow’s milk cheese common to the Açores {Azores}) with pepper and olive oil, bread, and olives.

Digression 1: In past days and still in some restaurants in 2024 some or all of these items might have been on the table when diners arrived or brought to the table without being ordered. This is the tradition of the couvert. If accepted, it incurred a charge. It is, as I noted in my very first post about Portugal, a tradition that’s fading – especially in Lisboa and especially in areas frequented by tourists. In fact, some restaurants now have signs or a note on their menu that diners can’t be charged for items they didn’t order. Still, like the increasingly rare restaurant that takes only cash, one should be prepared for the experience.

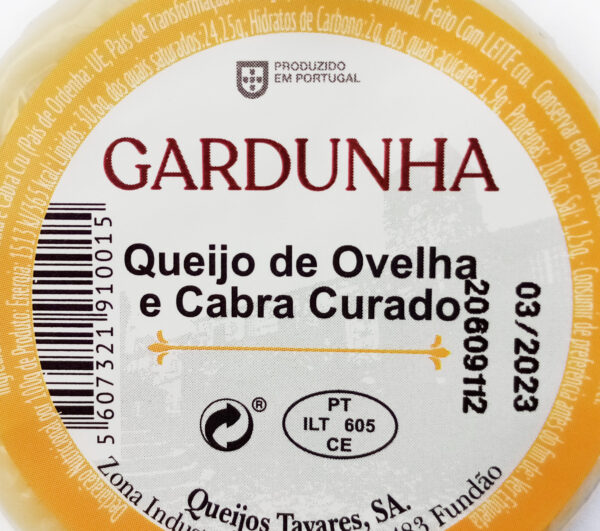

Digression 2: While cheese from the Açores is most commonly made from cow’s milk, most of the best of mainland Portugal’s cheeses (especially the artisanal cheeses) such as Serra de Estrela

[Photo from tasteatlas]

are produced using sheep’s or goat’s milk or sometimes a blend of the two. One such cheese is Gardunha. It can be made from leite de cabra {goat’s milk}, leite de ovelha {sheep’s milk} or a combination of the two as seen below.

[Photo from Openfoodfacts]

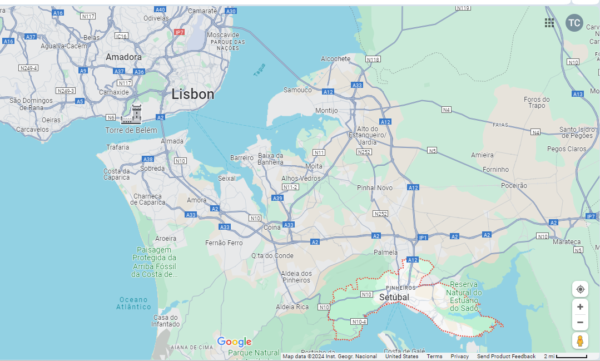

Before we finished nibbling on our entradas, our server presented our table with a serving of choco frito or fried cuttlefish accompanied, as many Portuguese dishes are, by French fries. Choco frito is among several signature dishes served at Casa dos Passarinhos and it gave us a broader exposure to regional Portuguese cuisine. Just as our cheese had come from the Açores, choco frito is a specialty of the Setúbal region (pronounced SHTOO-bahl) a coastal area some 45 kilometers south of Lisboa as seen in this Google Maps capture.

Typically, the cuttlefish is boiled with garlic and bay leaves, then marinated in lemon juice and wine. After this, it’s coated in seasoned corn flour and deep fried. The final product should be, as ours was, crunchy on the outside with a succulent slightly chewy inside.

Normally, choco frito with fries would be a complete meal – particularly when it’s following several starters but our meal here wasn’t nearly done. Now it was time for the main course a Caldeirada de Peixe or fish stew. Caldeirada de Peixe is a rustic regional dish that you can make anywhere in the world starting with whatever firm fleshed fish is native to your region. In Portugal, this includes monkfish, skate, ray, conger, John Dory, sea bream, and sea bass and it’s not unusual for a single stew to contain several kinds of fish. The version we had featured monkfish and prawns. The flavorful stew uses a fish stock usually supplemented with a quality white wine and good olive oil to intensify the flavors. A typical Caldeirada de Peixe is also replete with vegetables. Soups and stews seem to be the principal vehicle for Portuguese vegetable consumption. And, of course, we had the option of adding a kick of house made piri-piri to our fragrant dish.

Before moving on to our next stop (yes, there’s more eating to come), it’s time to take another look at the Portuguese influence on food most now consider Indian or, more precisely, Goan.

Sorpotel and Vindaloo.

If you’ve ever been to an Indian restaurant, you’ve almost certainly seen Vindaloo on the menu even if you haven’t ordered it yourself.

[By Adriao From Wikimedia Commons]

This spicy curry is such a staple of Indian cuisine that it might be hard to conceive it’s origins come from Portugal where highly spiced cuisine almost never emerges from the kitchen. If the Portuguese want a kick from something other than champagne they’ll add a dash of piri-piri but it will be wholly governed by their individual taste.

We know that the Portuguese reached India at the end of the fifteenth century and that they had conquered Goa by 1510. And we’ve seen how local Indian cooks were adding potatoes and green chili peppers to their local cuisine. Another type of food that accompanied those Portuguese sailors was carne de vinha d’alhos or meat in garlic and wine.

Fifteenth century sea voyages were lengthy affairs so in order to have preserved edible meat, the sailors borrowed a technique of packing alternating layers of meat (usually pork) and garlic into barrels then covering that with wine. This process either migrated from the mainland to Portugal’s Atlantic islands or it was developed in the Açores or on the island of Madeira. The actual origin is unclear.

As they did with peppers and potatoes, local cooks began adapting the Portuguese recipe to suit their own tastes initially substituting palm vinegar for the red wine because that wasn’t used in Indian cooking. Experimentation with different local spices continued, vinha d’alhos adapted linguistically to have a more locally appropriate pronunciation eventually giving rise to the spicy dish we know today as vindaloo.

Unless you been to the west coast of India or to a restaurant that specializes in Goan style food, I suspect you’re unfamiliar with sorpotel or sarapatel a dish that Dustysfoodieadventures.com (whence the photo below)

calls the “quintessential Pork dish that is part of almost every single Goan gathering.” This is another dish that originated in the Alentejo region and came to India after first stopping in Brazil. Because it usually includes most of the internal organs – heart, kidneys, liver, etc. – it’s referred to by some as Portuguese haggis. As it is with Vindaloo, the sauce is vinegar based and includes spice mixes that are quite individualized and closely guarded family or restaurant secrets. One key element in the preparation is that the sauce is made and cooked for several hours before the meat – which has likely been browned or parboiled first – is added.

I’ve touched upon three items of traditional Indian cuisine – vindaloo, sorpotel, and samosas – that either originated with the Portuguese or, in the case of the latter were heavily influenced by them. And, if you want to look, you can find several others. Given their rule over a relatively small area of a very large country the breadth of Portuguese influence is, for me, quite surprising. Perhaps this is because, as Albino Silva asserts, “Portugal didn’t really colonize, they integrated. The explorers sailed the world, lived in other countries, and married natives. This assimilation allowed the Portuguese to have more influence since they were already intertwined with the locals there.” Of course, other historians will tell you that the Portuguese were comparable to other Europeans and had a nearly equally ruthless approach to colonization. There are probably elements of truth in both. Nevertheless, the Portuguese influence is undeniable.

There’s still more food and history to come as I continue our Culinary Backstreets tour in the next post.