For a second consecutive day, we’d be up before the sun. We had to be on the bus by 06:15 for the roughly two hour ride to Cape Jervis where we’d board the Sealink ferry for its 09:00 departure to Kangaroo Island. This didn’t require any processing time for my reaction. One of my contemporaneous notes reads, “Way too early ferry.”

The time in Adelaide is thirteen and a half hours ahead of the time on the east coast of the U S so, although it was Wednesday the sixth in Australia, it was Tuesday the fifth in my homeland. I was a little surprised to see this headline

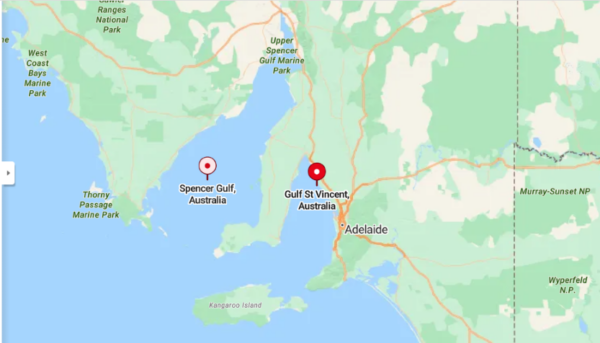

on a newspaper on a ferry crossing the narrow stretch of water called Backstairs Passage between Cape Jervis and Kangaroo Island. (Matthew Flinders named the passage, noting in his journal, “…it forms a private entrance, as it were, to the two gulphs (sic); and I named it Back-stairs Passage.” The two gulfs are Gulf Saint Vincent and Spencer Gulf.)

[From Bing Maps]

Bust a myth

(We’re the quick who’ll soon be dead.)

Although it was uninhabited by humans when Flinders arrived in 1802 and named the place Kangaroo Island, there is considerable archaeological evidence that local indigenous Australian People had inhabited the island at one time. Kangaroo Island likely separated from the Australian mainland in the same way and at the same time as rising sea levels enisled Tasmania. Two Aboriginal nations, the Kaurna and Ngarrindjeri Peoples have their traditional Country on the coast not far from Kangaroo Island and it’s likely that in times past individuals from one or both of these nations inhabited the land before it became an island and possibly for sometime after.

In the Kaurna Miyurna language the island is split into two parts. The eastern half is called Karta and the western side is Pintingka. Although it’s not uncommon to see the island referred to as Karta Pintingka, the names hold specific somewhat different concepts. Karta refers to the “island of the dead” while Pintingka is the “place of the dead.” The Ngarrindjeri People also use and understand Karta in the same way as the Kaurna.

As for Captain Flinders, he and his crew were completing the first known circumnavigation of the continent when they reached the island and had been sailing for four months on quite limited rations. The island has a unique subspecies of the western gray kangaroo. It’s smaller, sturdier, and has darker fur than its mainland cousins. Because it lived in isolation with no human contact or other natural predators, the Kangaroo Island kangaroo is, even today, among the friendliest and is the slowest moving of its species. (The one in the photo below wandered into the store at Emu Ridge Distillery during our visit there late Thursday afternoon.)

When Flinders and his crew landed on the island, it was reported that the entire ship’s crew of 94 spent the next three days hunting, skinning, and consuming kangaroos – reportedly eating 31 kangaroos over that period. In his journal, Flinders wrote, “…in gratitude for so seasonable a supply, I named this south land KANGAROO ISLAND.”

While I’m on the subject of kangaroos, let me dispel the somewhat common notion that the name originated from a misunderstanding where a group of Indigenous People said “we do not understand”. This is not true. The first recorded use of the word came in 1770 when Captain James Cook and botanist Joseph Banks, exploring the area in far northern Queensland that’s home to the Guugu Yimidhirr people, recorded it as ‘kanguru’. In his 1972 study of the Guugu Yimidhirr language, anthropologist John Haviland, corroborated the use of “gaNurru” by the Guugu Yimidhirr People thereby reconfirming its true origin.

Yes sheep, Sherlock

Once the ferry docked at Penneshaw the group reassembled, boarded the bus and took a short 15 or 20 minute ride to Rob’s Shearing and Sheepdog Demo. Rob Howard is a third generation sheep farmer and shearer whose farm has been in his family since 1883. The first sheep farmers came to the Island in 1836. Those early farmers struggled because of the mysterious “Coast Disease” afflicting their sheep that turned out to be a cobalt deficiency. In 1847, Charles Oliver accompanied ten and a half bales of wool on the cutter Resource. This was the first recorded shipment of wool from the island.

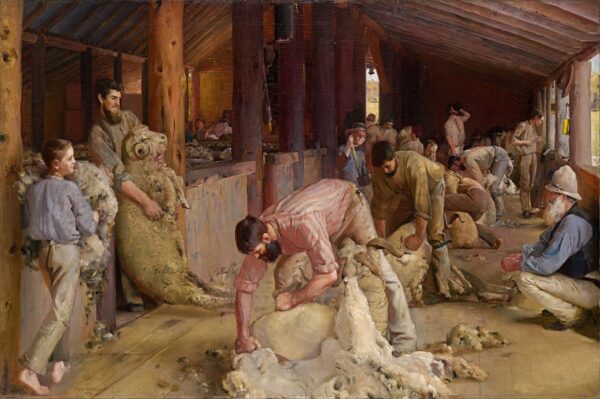

Our show began with a pair of Rob’s dogs herding the sheep into the shearing shed where he proudly had a copy of Tom Roberts’ famous 1890 painting Shearing the Rams – making certain we noticed the famous detail of the “smiling tar-boy” who is the only figure in the painting making eye contact with the viewer. His job would have been cauterizing any wounds on the sheep that the shearers opened.

[Google Art Project]

This part of the demo was a bit rough. (You can see a video of the dogs herding in the photo album linked below.) Each dog has a different task and is taught a different approach and, although one seemed to be in semi-retirement and the other in training, apparently neither had learned to say “Baa-ram-ewe!”

Rob is a skillful raconteur who amused us with his tales of his family history, the boom and bust cycles for the wool industry, and the other challenges facing the island’s sheep farmers all while he was turning a wool heavy sheep into one that looked like this:

(Fulfilling the jokes about Australia, the island has a population of more than 100 sheep {500,000} for every person {4894 in 2021} who lives there.)

After our picnic lunch, we’d close out the day’s activities with a stop at the questionably named Seal Bay Conservation Park. Want to guess what we saw there? If you guessed seals, you’d be wrong. We saw Australian sea lions. In fact, we were at the third largest breeding colony in the world of this endangered species. The two larger colonies are at Dangerous Reef and the Pages Islands both in SA.

Besides their ear flaps (sea lions have them and seals don’t) one of the other differentiators between the two is that sea lions are much noisier – a fact that greeted us soon after our arrival with this young female – they are usually described as ash gray – being the main noisemaker.

These pinnipeds were nearly hunted to extinction for their skins in the 19th century and only an estimated 10,000 – 12,000 survive in the wild today. Because both breeding females and their pups tend to return to the same colony every year, very little cross breeding occurs between colonies. One remarkable fact we learned is that when they leave the beach to feed, they will typically spend three days devouring rock lobsters, octopuses, small rays, and sharks before returning to the beach to rest, feed their young, and spoon.

From Seal Bay, we bused back across the island to our hotel in Kingscote. This was another hotel restaurant dinner but it turned out to be quite an unpleasant experience for some in our group. Four people got violently ill and two were hospitalized. None of the four would be well enough to join us on the morrow.

Meanwhile, here’s where you can find the other photos from the day and the video I promised above.