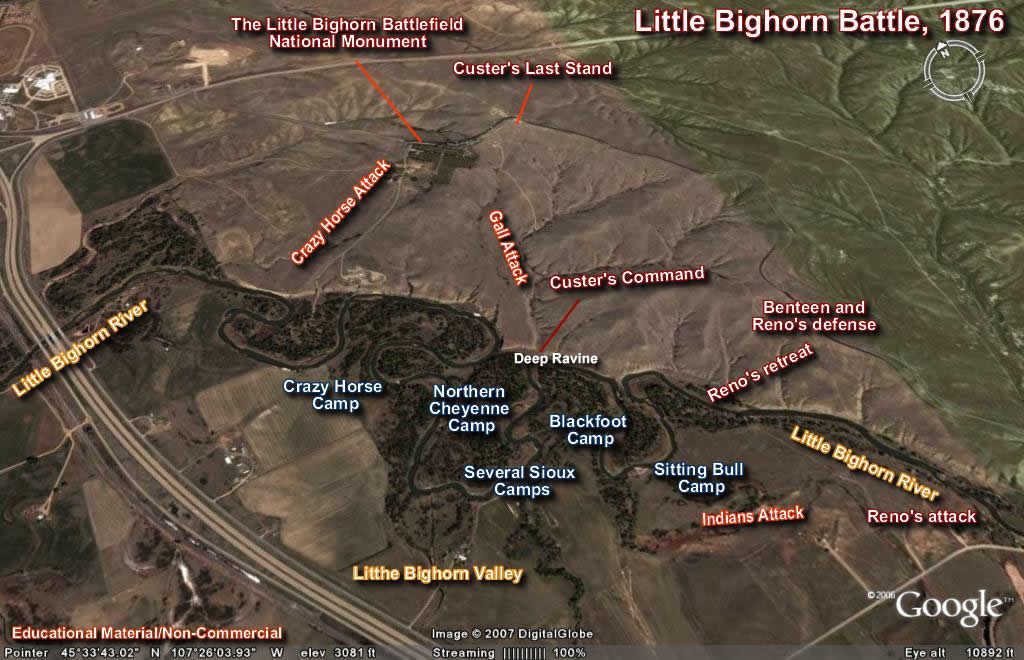

As a reminder, here’s an aerial look at the battlefield.

Recall that Custer had a force of nearly 600 soldiers and officers and sent only 125 with Reno but we also know that 210 rode into the final battle with Custer at Last Stand Hill. Where then are the remaining 260? Custer assigned three companies (D, H and K) to the command of Captain Frederick Benteen to embark on a lateral scouting mission and to protect the supply train and packs.

During this stage of the battle, Reno was beside his scout, Bloody Knife, when the latter was shot in the head. Understandably, this disoriented him and as the blood-and brains-spattered and panicked Reno sought safety on the bluffs, Benteen was responding to a handwritten message from Custer, “Benteen. Come on, Big Village, Be quick, Bring packs. P.S. Bring Packs.” This dual mention of bringing packs would have certainly underscored Custer’s sense that he was already facing a dire situation. As Benteen was driving his troops and train north to respond to Custer’s message, he arrived at what is marked on the aerial view at the top of this post as “Reno-Benteen Defense.”

Reno still hadn’t recovered from the shock of being splattered with the skull fragments of his Arikara scout and Benteen likely saw the troops reflecting their commander’s disorientation. It’s possible that he also had some sense that the warriors of Crazy Horse and Chief Gall were closing in on Custer although that fight was some five miles distant. Effectively, he was caught Ben-tween a rock and a hard place. He could continue across the field in response to Custer’s orders which would have almost certainly sealed Reno’s fate and possibly that of his own men or he could, as he chose to do, organize the defenses for both his battalion and what remained of Reno’s.

Certainly, we’ll never know the degree to which the personal animosity between Benteen and Custer influenced the former’s choice or whether he made what he believed was a sound military decision. Custer’s defenders and promoters want everyone to believe the former. Of this we can be sure, nearly all Benteen’s men and those under Reno’s command who reached the defense line that Benteen created survived. Only one person under Custer’s command, his Crow scout Curly, survived. No one else, including the Lieutenant Colonel himself, did. (Curly’s account of the battle is here.)

Was there really a last stand?

[Edgar Paxson – Custer’s Last Stand – Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

As nearly as I can tell, the first scholarly work asserting that Custer did not make a last stand at the battle of Little Bighorn appeared in 1993 in Doct0r Richard A Fox’s book Archaeology, History, and Custer’s Last Battle. In the quarter century since its publication, Fox’s book has stirred renewed debate about the battle at Greasy Grass. His book (of which I have only read reviews) concludes that the 210 men under Custer’s command “simply disintegrated under fire.”

Combing the battlefield, Fox used evidence from several hundred bullets and cartridge cases, nine iron arrowheads, three pieces of guns, scores of buttons and quantities of human bone belonging to at least 33 people to support his conclusion. Using a multi-disciplinary approach that included techniques from forensics as well as archaeology, he deduced that Custer’s men were engaged in offensive, not defensive action.

He asserts that the disintegration started in Company C while it was trying to clear Indians out of what is called the Deep Ravine about half a mile from Last Stand Hill.

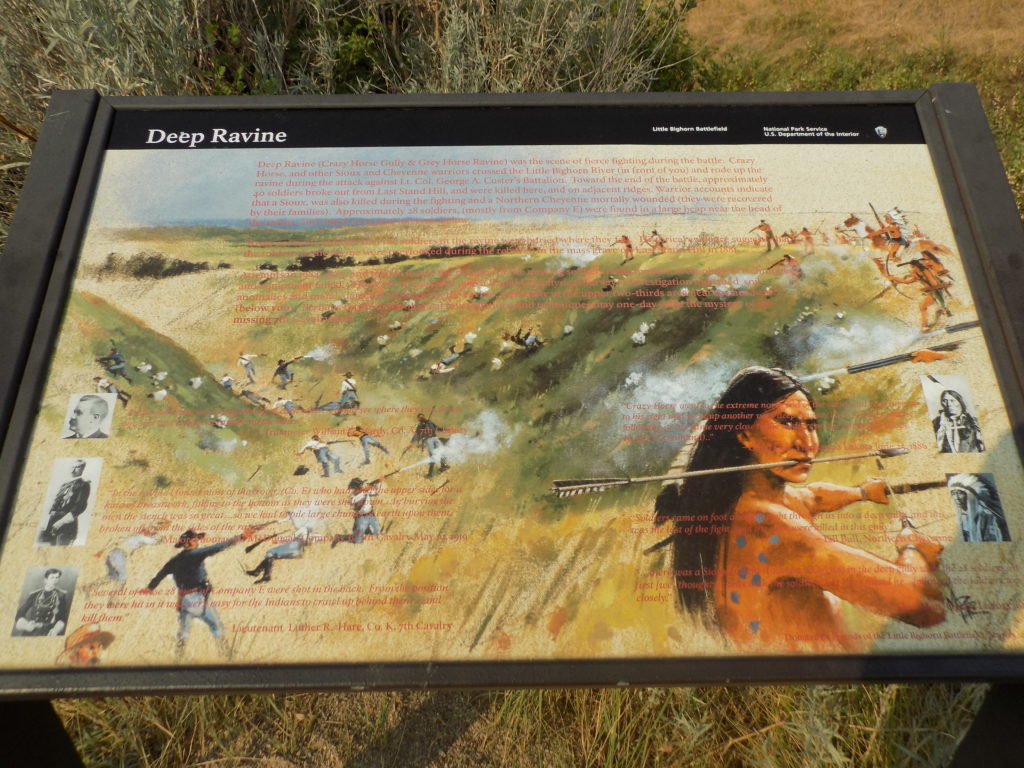

Even enlarged, this marker is difficult to read but it states that 40 soldiers broke out from Last Stand Hill near the end of the fighting and that the bodies of 28 soldiers (mainly from Company E) were found near the head of the ravine. This is supported by a letter written by Lieutenant Charles Roe who arrived with General Terry two days after the battle and returned to the field in 1881 to rebury the bodies on the ridge and place the stone monument above them. “I put up the markers near the deep ravine you speak of. There never was twenty-eight dead men in the ravine, but near the head of said ravine, and only two or three in it.”

Another source claims that while battle relics and bones have been found virtually on every part of the Little Bighorn Battlefield, they have not been found in the trench of the Deep Ravine. All of this comports with the statements of some surviving warriors who stated that no more than four of the soldiers died in the ravine.

Fox continues his portrayal of the disintegration of Custer’s Troops stating that the Lieutenant Colonel sent troops toward the ravine in an attempt to distract the Indians while he sent five mounted troopers south in an attempt to get help. These actions reduced the men on Last Stand Hill to no more than 60.

Markers such as these

for 7th Cavalry fatalities and these in red granite

for the Native Americans dot the entire battlefield and are intended to mark the spot where that person died. From my vantage point and memory, the area at the 7th Cavalry memorial

contains 60 or fewer markers making this aspect of Fox’s conclusion unremarkable – at least to me. The one that stands out with the brown marking is Lieutenant Colonel Custer’s. (Custer’s youngest brother Boston also has a marker on the hill.)

Many of the warriors who survived the battle spoke of the last stand, Chief Gall, standing near the ridge not far from the hill said, “They were fighting good.”

Red Hawk said, “The bluecoats were falling back steadily to the hill where another stand was made. Here the soldiers made a desperate fight.” There are many similar Native American accounts.

Perhaps all Fox claims is that there was no great last stand like the one portrayed in legend, in Paxon’s painting, or even in the movies. To me, it seems clear that be it 100, 60 or even only 40 men, there was something of a last stand on that hill.

With the battle over, I urge those of you interested in its history not to take mine as a final or definitive word. While I’ve tried to present a balanced view, my research is far from thorough and any conclusions are my own and affected by my world view.