These are some things we know for certain about the events at Little Bighorn on 25 June 1876:.

- Custer led the 7th Cavalry (566 enlisted soldiers and 31 officers) that was accompanied by as many as 40 scouts – many from the Crow, Arikara and Pawnee tribes – and some number of civilians (including Isaiah Dorman who served as an interpreter and was the only black man attached to the otherwise segregated unit) into a battle with a group of Lakota Sioux, Arapaho and Cheyenne warriors who were led by Crazy Horse and Chief Gall.

- 268 Americans died on the battlefield including all of those who were with Custer.

- Another six would die later of wounds suffered during the battle.

- The Indians repulsed Major Marcus Reno’s surprise attack on their village.

- Captain Frederick Benteen chose to aid Reno’s retreat rather than coming to Custer’s aid.

We also know that the battle was nothing like the one portrayed in the Erroll Flynn movie They Died With Their Boots On. Beyond this, much is lost in the fog of war.

Recall that the broad plan developed by General Alfred Terry was to subdue the “hostile” plains tribes with a three-pronged attack. (They knew the general movements of the tribes through southeastern Montana and northeastern Wyoming but weren’t aware of their specific location.)

The force under Colonel John Gibbon would march east and south from Fort Ellis while the second group led by General George Crook marched north from Fort Fetterman and the third group under Custer’s leadership, the 7th Cavalry, would march west and south from Fort Lincoln. Initially planned for early spring, the assault was derailed when Custer was called east to testify in the Trading Post Scandal. This delayed their departure for several weeks.

The additional time allowed the three so-called hostile tribes to gain several advantages. From a military standpoint, both Crazy Horse (Tȟašúŋke Witkó) and Chief Gall (Phizí) acquired more arms and more warriors. Psychologically, the tribes received an immense morale boost from Sitting Bull (Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake) who, in the late spring performed the Sun Dance – a ritual requiring a fast and the sacrifice of over 100 pieces of flesh from his arms – and had a vision in which he saw many soldiers, “as thick as grasshoppers,” falling upside down into the Lakota camp.

One more important battle before Little Bighorn.

Once it finally got underway, Terry’s plan hit its first snag on 17 June in the Battle of the Rosebud (also referred to as the Battle of Rosebud Creek) or, as the Cheyenne would call it, the Battle Where the Girl Saved Her Brother.

(Crook had, perhaps mistakenly, encountered the Cheyenne before. Certainly, forces under his command had. On 17 March 1876, the Second and Third Cavalry regiments led by Colonel Joseph J Reynolds as part of the Bighorn Expedition (another U S Army military operation against the Sioux “hostiles” in the Wyoming and Montana territories), attacked a village along the Powder River that they believed to be a camp of Oglala Sioux under Crazy Horse. As it turns out, this was a group of Northern Cheyenne. The mistaken attack prompted the Cheyenne, who now saw themselves as targets to become enthusiastic allies of Crazy Horse and the Sioux and, with Terry’s plan delayed by Custer’s time in Washington, bolstered the ability of Tȟašúŋke Witkó to build an ever larger force.)

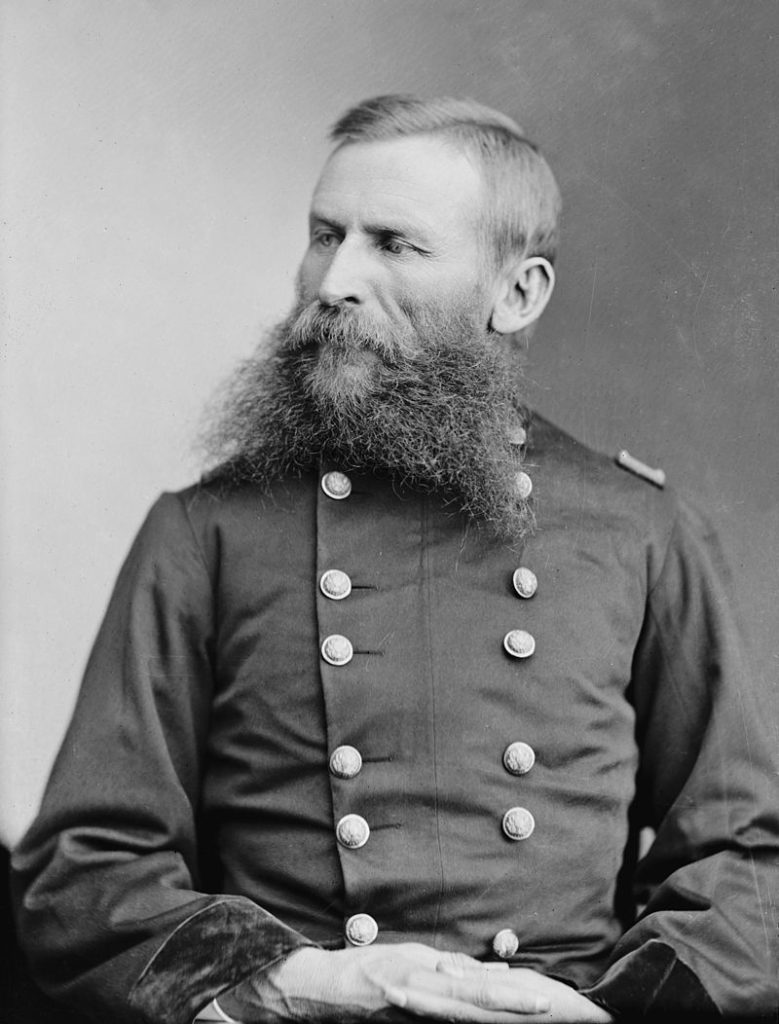

Leading a force of 993 cavalry and mule-mounted infantry, 197 civilian packers and teamsters, 65 Montana miners (one of whom is said to have been Calamity Jane whom we’ll meet in more detail when I visit Deadwood tomorrow), three scouts, and five journalists, Crook left Fort Fetterman in early June along the now abandoned Bozeman Trail.

[Photo of George Crook – Wikipedia – Public Domain.]

On 8 June, Crook’s force reached its base camp at Goose Creek (near present day Sheridan, Wyoming). Crazy Horse, inspired by Sitting Bull’s vision and who had assembled an army of more than 1,000 warriors of his own, had threatened to bring the fight to Crook (whom he called “Three Stars”) if he crossed the Tongue River. After a late-night foray by the Cheyenne on 9 June that killed two of his soldiers, Crook’s inaction made it appear that he had some concern about Crazy Horse’s claim. In truth, he was awaiting the arrival of an additional 260 Crow and Shoshone warriors who, no doubt, happily anticipated inflicting punishment on their long-time enemies.

A confident Crook allotted four days rations and 100 rounds of ammunition to each soldier and left his civilians behind to guard the wagons and pack train. He then headed north marching 35 miles toward the headwaters of the Rosebud on 16 June. At the same time, Crazy Horse set out with his band of warriors. Crook stopped to rest his men along the south banks of the Rosebud. Although he made no special provisions to defend his position, he sent several Crow and Shoshone to act as scouts and lookouts on the bluffs above the river.

Fortunately for Crook, it was on these bluffs that Crazy Horse began his attack at about 08:30 and while the Crow and Shoshone were substantially outnumbered, they were able to hold off the Sioux long enough for Crook to deploy his forces. The battle, which lasted approximately six hours, devolved into a series of retreats and advances on both sides.

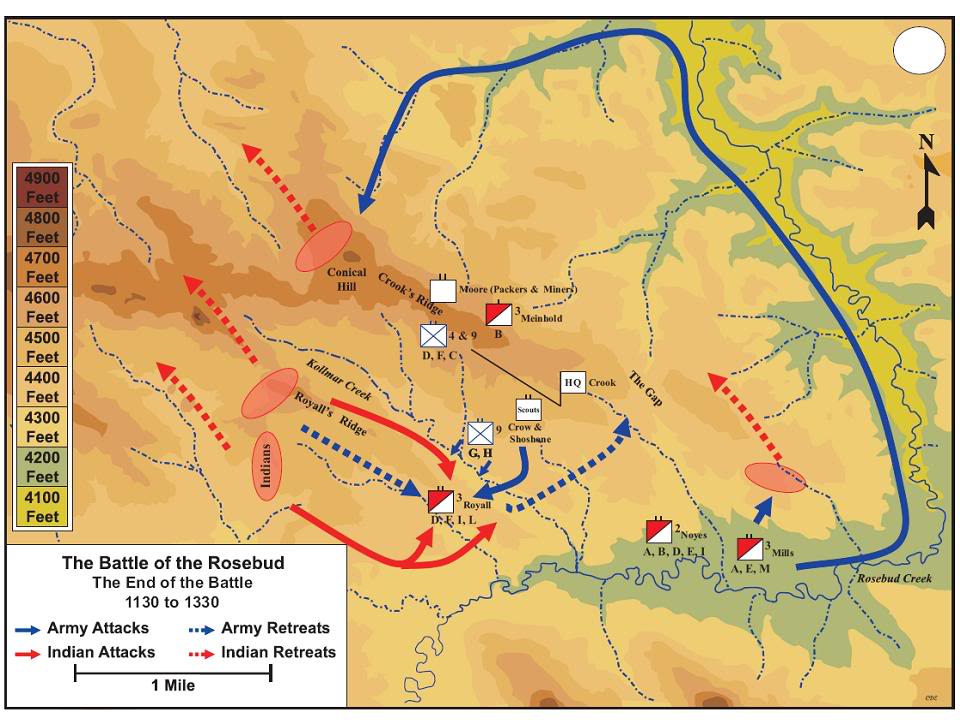

[Map of the Battle of the Rosebud from Military-Wiki.]

At the end of the day, the Lakota retreated to the northwest (as shown by the red arrows) Crook’s cavalry initially pursued them but soon gave up the chase allowing the Indians to safely regroup. With his supplies and ammunition depleted, Crook chose not to continue north. It’s unclear why but he failed to notify General Terry or Lieutenant Colonel Custer that his expected support wouldn’t be forthcoming. Gibbon’s force, the 7th Infantry of Montana, then met the column led by Custer and Terry on 21 June near present day Rosewood, Montana.

At the battle’s end, Crook claimed only 10 dead and 21 wounded. However, a top aide reported 57 total casualties and one of his interpreters, Frank Grouard, reported 28 dead and 56 wounded. Estimates of Lakota and Cheyenne casualties are equally vague ranging from as few as 10 to as many as 100.

Though Crook claimed a victory because he held the field after Crazy Horse’s retreat, his actions belied those assertions and the battle was a standoff at best. He withdrew his largely incapacitated column back to its base camp at Goose Creek where it would spend nearly two months. Crazy Horse’s attack and Crook’s withdrawal ended Terry’s planned three-pronged attack. With Gibbon’s slow pace, when Custer arrived at Greasy Grass, though he didn’t know it, the expected reinforcements weren’t nearby. He was on his own.

Having stopped Crook’s advance, the Lakota felt some realization of Sitting Bull’s vision. Nine days later, a newly invigorated Crazy Horse and many of those same warriors would fight in a battle some 40 miles to the north. That battle, the last Indian victory in the Great Sioux War, would have a much more decisive outcome.

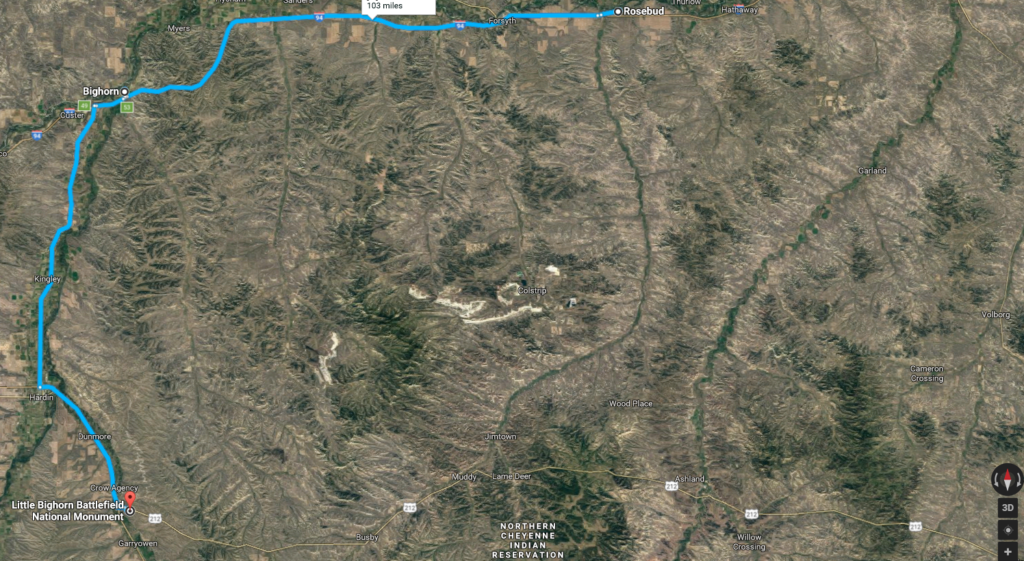

Without knowing what had happened to General Crook’s forces five days earlier, Custer started south essentially following Rosebud Creek toward Little Bighorn. Gibbon turned his forces around and marched with Terry toward the Little Bighorn River approximately 50 miles west before turning south toward the Indian Village. They wouldn’t arrive at the battle site until 27 June.

(The blue line on the satellite view from Google maps approximates the route Terry and Gibbon followed. Custer turned south following what appears as a green line on the unenlarged map. To see Custer’s route, enlarge the map and find Jimtown, Muddy, and Busby.)

(Some controversy exists regarding Terry’s final orders to Custer and whether Custer disobeyed those orders. Here’s a partial text of the final written orders.

The Brigadier-General Commanding directs that, as soon as your regiment can be made ready for the march, you will proceed up the Rosebud in pursuit of the Indians whose trail was discovered by Major Reno a few days since. It is, impossible to give you any definite instructions in regard to this movement, and were it not impossible to do so the Department Commander places too much confidence in your zeal, energy, and ability to wish to impose upon you precise orders which might hamper your action when nearly in contact with the enemy. He will, however, indicate to you his own views of what your action should be, and he desires that you should conform to them unless you shall see sufficient reason for departing from them.

In addition, there was testimony that Terry entered Custer’s tent the night before his departure and told him, “Use your own judgment and do what you think best if you strike the trail.” Though I think this evidence should have put the alleged controversy to rest, it nevertheless persists.)