Custer’s Last Stand – the battle that shocked America.

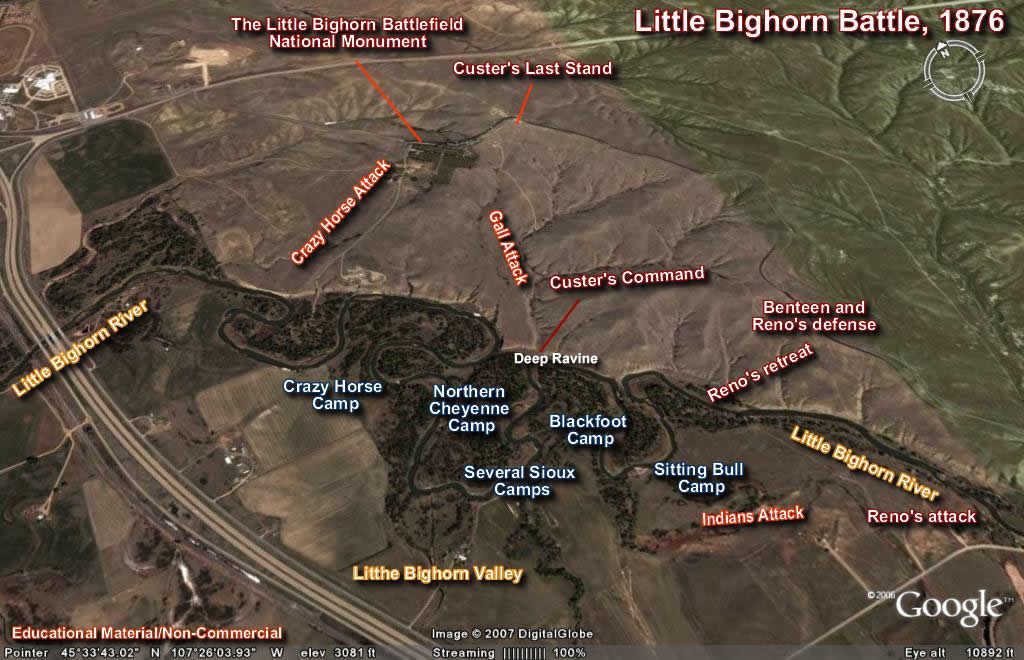

I don’t recall the source of the aerial photo below but keep it close because it highlights most of the important positions that I’ll mention in my description of the battle and the battlefield.

As you can see, today, the Indian Village and the battlefield are just north of an interstate highway (in this case I-90). As I made the short drive from the highway to the Visitor Center, my first impression was that┬Āhad a battle that made a near mythic imprint on the American psyche not occurred in this place, it would be little more than an ordinary field that travelers along the interstate would ignore.

Certainly, I claim no military acumen but, given its location in the plains of Montana and looking at the battlefield itself regardless of my view point whether from near Last Stand Hill,

or this one of the Deep Ravine,

or this one from the Reno-Benteen Line,

or any of the others, I couldn’t see any strategic importance to the place. I have to think the battle happened here because this is where the Sioux and their allies happened to make their camp.

So What Happened?

Much of the historical picture we have of what actually occurred in the battle at Little Bighorn comes from manipulated testimony made at a military hearing, a willing press that sometimes tacitly and sometimes actively portrayed Custer in the way his widow promoted his image, and the reticence of many of the surviving Native Americans to speak ill of the man because they feared government reprisals.

When we last saw Custer on 22 June 1876, he was taking his troops south along Rosebud Creek while Terry and Gibbon marched west toward the Bighorn River where they planned to turn south. All three expected that General Crook’s column would provide support from the south at a place on the river where there were reports of a large Indian village. On 25 June, Custer and his troops arrived at a spot known as the Crow’s Nest about 15 miles east of the Greasy Grass Valley.

Initially, the scouts saw no village. However, they did see smoke rising from behind the bluffs to the west. They proceeded west to investigate and, even at this point, events become a bit obscured. Some accounts say that the scouts reported seeing an enormous pony herd and signs of a huge village with one scout reportedly telling him that it was the largest village he’d ever heard of. Other scouts are said to have reported a large village but not overwhelmingly so.

When Custer, even with the aid of binoculars, tried to see the village, he saw little or nothing. That’s understandable. He and his men had marched all night, they were tired and, from their vantage point, the area looked like this:.

[Photo above from butbeingmen.blogspot.com]. Looking back from the battlefield you have this view.

In the above photo from the National Park Service, the Crow’s Nest is marked (1.) and the Little Bighorn River is (2.). The spot marked (3.) is where Custer ordered Reno to march forward to attack the village which is outside the frame. So, it’s little wonder that Custer didn’t see the village – particularly since accounts provided by various tribesmen confirm that it was considerably smaller than it grew to be in building the myth of the battle. In some accounts the village grew to a length of six miles and a width of a mile. (Here’s one source reporting┬Ā how the size of the village increased.)

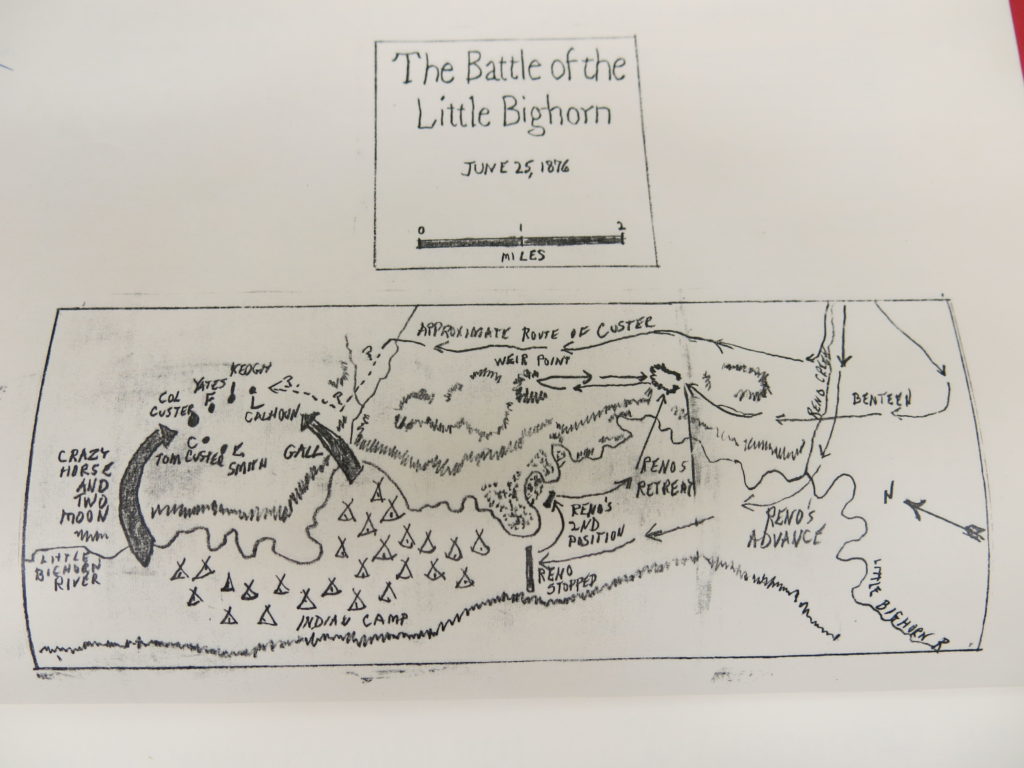

James E Dean, Junior’s hand drawn map (reproduced in the Asheville Mountain Xpress) perhaps provides a better perspective.

It was certainly a large village and, preferring rested troops and the element of surprise, Custer wanted to wait until the morning of 26 June to launch his attack as he had at Washita. However, one of his Crow scouts, Half Yellow Face, warned that the Sioux had seen the smoke from the camp at the Crow’s Nest and asserted that they should attack immediately. Custer remained unconvinced until soldiers discovered Indians rummaging through some supplies they had dropped on the back trail. At that point, Custer decided he had to attack.

Dividing the Force.

You may recall that in his successful battle at Washita, Custer employed a tactic where he used one force to draw warriors away from the village while he circled behind and captured non-combatants (women, children, and the elderly) and used them as human shields to force the Indians to surrender. There’s some speculation that he intended to use a similar tactic at Greasy Grass.

Whether or not this is the case, by ordering Major Reno to attack (in this instance from the south) Custer employed a standard military tactic: dividing his forces to engage the enemy on one front while sending another group to envelop the flank – support that Reno expected. Reno took three companies (A, G and M) totaling about 125 men and crossed the river at what is known today as Reno’s Creek.

Had Custer tactically blundered? Perhaps. There’s certainly reason to believe that while the Indian Village wasn’t as large as subsequent legend made it, it was larger than Custer suspected (since he hadn’t seen it himself). Had he known its size, he would have realized that dividing the regiment couldn’t be successful against such a large force and would almost certainly have altered his attack plan. On the other hand, it’s possible that his recent humiliation at the hand of President Grant and in front of General Terry might have combined with his lack of respect for his tribal foes enflamed his daring spurring him to act in a reckless way he thought would gain him a great victory.

Although Reno later testified to the court of inquiry that when he saw the size of the village he suspected a trap and, “So numerous were the masses of Indians encountered that the command was obliged to dismount and fight on foot…”, it’s equally likely that Reno and his supporters (who also testified) were trying to restore his reputation which had been considerably sullied by the campaign to lionize Custer.

All the reports from the Indians belie the notion that Custer and his forces had walked into an ambush. In fact, despite attacking in the middle of the morning, it appears from their later testimony that Custer was successful in surprising the village. One strong piece of evidence supporting the notion that Reno’s attack was, indeed, a surprise is the name Abandoned One given to a young child of Sitting Bull’s. The name reflected the fact that the attack had so frightened his wife, Four Robes, that in her panic, she grabbed only one of her infant twins and ran to the hills. When asked where the second child was, she realized she had left it behind, and raced back to the lodge to retrieve it. Sitting Bull himself was said to have been bathing at the time.

Though his attack surprised the village, the warriors responded within an hour at most. Again, using standard tactics, Reno had most of his men dismount and form a skirmish line while some remained on horseback and rode into the trees to provide cover. As the Indians pushed back, Reno withdrew to his second position waiting for Custer’s troops to arrive with the expected support.┬Ā This video provides a succinct recap.