If you’re an enthusiast of historic milestones and I asked you to name the location of one that happened in May 1927, I’d guess the first place that would come to your mind would be Paris, France not Bath, Michigan. What happened in Paris, (well, near Paris) on 21 May of that year is well worth remembering. What happened in Bath, Michigan three days earlier is also worth remembering but for an entirely different reason.

Of course, enthusiasts can celebrate Charles Lindbergh landing the Spirit of Saint Louis at Le Bourget 33 hours 29 minutes and 30 seconds after leaving Roosevelt Island in New York thereby becoming the first person to complete a solo non-stop trans-Atlantic flight. As for what happened in Bath, here is the headline about the story from the May 19 New York Times: “Maniac Blows Up School… Had Protested High Taxes”. Forty-five children and teachers died that day and another thirteen were injured in what remains the worst school massacre (or as the historical marker at the site calls it “disaster”) in the history of the United States.

Quanto mais as coisas mudam.

The header for this section translates as “the more things change.” There’s a second part to this aphorism that should be familiar to most. Gun violence is epidemic in the United States and all too frequently schools have been the target. Since the 1999 mass shooting in Columbine, Colorado, there have been 17 additional school massacres killing 185 people and wounding 153. But, according to this Wikipedia page, these events even predate the republic’s establishment with the very first school “massacre” taking place in Greencastle, Pennsylvania on 26 July 1764 (in what today we would almost certainly call an act of terrorism by the Native Americans who perpetrated it).

T0 date, the highest death toll from a mass shooting in the U S happened in 2007 at Virginia Tech University ending the lives of 33 people (including the shooter). Thirty-two people were injured and six (including the shooter) killed in a 1989 assault on Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California. According to World Population Review from January 2009 through May 2018 there were 288 school shooting events reported in the United States though not all involved fatalities. Mexico was second on the list with eight.

Although not a shooting, the massacre at Bath Consolidated School

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

killed 38 children and 7 adults and left at least 58 wounded.

Because he killed himself on the day of the massacre, we will never be certain what motivated Andrew Kehoe to commit his meticulously planned and unfathomably heinous act. However, authorities at the time put forth what appears to be a reasonable explanation.

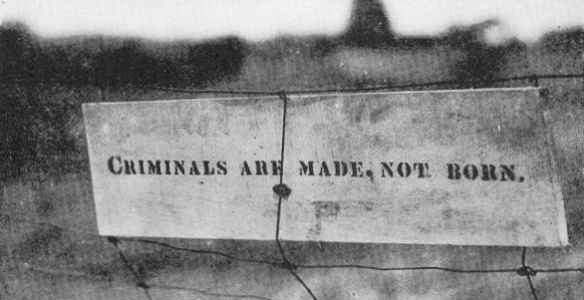

Criminals are made, not born.

Investigators found this sign on a fence at the remains of Kehoe’s farm

[Photo from Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

so it behooves us to look at the circumstances that might have made Kehoe a criminal. Or at least to have committed his criminal act.

Although he had reportedly spent some time working near Saint Louis, Missouri as an electrician, Andrew Kehoe was a Michigander. Born in Tecumseh, some 80 miles southeast of Bath, he received a degree in Engineering from Michigan State University. After his time in Saint Louis, he returned to Michigan where he married his college sweetheart, Nellie Price. He eventually bought a farm in Bath in 1919 from Price’s mother’s estate though, according to reports, he always seemed more interested in tinkering with his farm machinery or helping his neighbors with theirs than he was in farming. According to M J Ellsworth’s book The Bath School Disaster, “He spent so much time tinkering that he didn’t prosper.”

The website Verywellmind describes obsessive compulsive personality disorder (once called anal or anal-retentive) as follows:

Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) is defined by strict orderliness, control, and perfectionism. Someone with OCPD will likely try to stay in charge of the smallest details of their life, even at the expense of their flexibility and openness to new experiences.

OCPD is a personality disorder, which means it involves personality traits that are stable, long-held, atypical, and problematic in some way. In the case of OCPD, people with this condition may find it hard to relate to others, and their devotion to perfectionism and rigid control can make it difficult to function.

In many ways, this seems an apt description of Andrew Kehoe. According to Ellsworth,

The writer interviewed some of Andrew Kehoe’s neighbors and classmates of that locality. They all told practically the same story. He was comparatively sociable when he was in school but as he grew older, he became more distant and more inclined to want his own way. He didn’t want to have anything to do with people who didn’t do as he wanted them to.

And,

He never attracted much attention around the neighborhood. There was something about him that no matter how good a friend you thought you were of him, there always seemed to be a distant feeling. He would give you a straight answer with no explanation.

A set of circumstances beginning in 1925 when he was serving as both treasurer of the Bath Consolidated School Board and as the Bath Township Clerk may have played a motivational role in the tragedy of 18 May 1927.

Piling on.

By all reports Kehoe was obsessively thrifty and was always pushing for lower taxes while on the School Board often adjourning meetings when the other members voted against his wishes. He frequently clashed with the superintendent on the board as well.

Nevertheless, he was appointed to fill the term of the township clerk when she died wile still in office. He failed to win his 1926 bid to be elected to the post.

[Photo of Andrew Kehoe – Wikimedia Commons – Public Domain.]

But it wasn’t the loss of an election alone that weighed upon Kehoe and might have created the sense that his life was spiraling out of control. Sometime in 1925, his wife contracted tuberculosis and his failures as a farmer left him so deeply in debt that he’d stopped making his mortgage payments. It’s likely that had the debt been held by a bank rather than by Missus Kehoe’s family, he would have faced foreclosure far earlier.

In the fall of 1926, Kehoe bought some 500 pounds of dynamite in the form of pyrotol – a leftover explosive from the First World War commonly used by farmers for removing tree stumps and the like. Although this didn’t raise any warning signals, particularly since he offered to share it with his neighbors, his apparent lone use before the disaster could have.

There had been a New Year’s Eve explosion on Kehoe’s farm and when a neighbor asked about it, “Kehoe told him he was just trying out a clock system. He said that he put the dynamite out in the garden and the clock down cellar and set it for twelve o’clock.”

The fateful day.

Kehoe was quite methodical in the time between that fateful New Year’s Eve explosion and 18 May 1927. He likely made several trips to the school strategically placing his dynamite and meticulously completing the wiring of the explosives. In fact, according to Charles Lane, the state fire marshal, this was so well done that he wasn’t sure it could have been installed by one person.

Triggered by an alarm clock, one batch of Kehoe’s dynamite exploded in the north wing of the school killing 38 people. Kehoe was still at his farm where he had either already murdered his wife or did so that morning after the initial explosion. He also set fire to the farm before setting out toward the school with his truck loaded with yet more explosives.

Once he reached there, he engaged in an argument with E E Huyck, the school board superintendent with whom he’d repeatedly clashed while serving on that body. About 30 minutes after the first explosion Kehoe detonated the truck bomb killing himself, the superintendent, and three others nearby.

As horrific as the day had been, it could have been far worse. Investigators found a short circuit in the wiring of a similar load of dynamite in the south wing of the building that left it unexploded. So, although Charles Lane might have believed the installation required more than one person, scores of Bath’s children were fortunate Kehoe wasn’t truly a master blaster.

Today, the town maintains a small memorial in a park near the current school location. The dome of the original school

is the centerpiece. You can see a few other photos I took in this album. If you’re unsatisfied by my sketch of this event, you can find the definitive recounting in Harold Schechter’s book Maniac: The Bath School Disaster and the Birth of the Modern Mass Killer.